Amerigo Vespucci facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

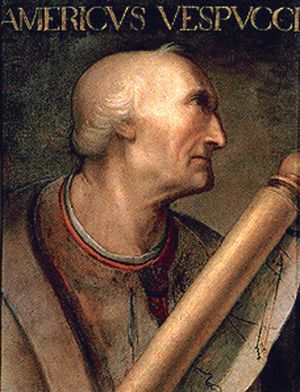

Amerigo Vespucci

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 9 March 1454 Florence, Republic of Florence

|

| Died | 22 February 1512 (aged 57) |

| Other names | Américo Vespucio (Spanish) Americus Vespucius (Latin) Américo Vespúcio (Portuguese) |

| Occupation | Merchant, explorer, cartographer |

| Known for | Demonstrating to Europeans that the New World was not Asia but a previously unknown fourth continent, Being whom the Americas are named after. |

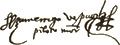

| Signature | |

|

|

Amerigo Vespucci ( 9 March 1454 – 22 February 1512) was an Italian explorer and navigator. The term "America" derives from his name.

Contents

Early life and education

Vespucci was born on 9 March 1454, in Florence, a wealthy Italian city-state and a center of Renaissance art and learning.

He was the third son of Nastagio Vespucci, a Florentine notary for the Money-Changers Guild, and Lisa di Giovanni Mini.

Amerigo was tutored by his uncle, Giorgio Antonio Vespucci, one of the most celebrated humanist scholars in Florence at the time. He provided young Vespucci with a broad education in literature, philosophy, rhetoric, and Latin. Amerigo was also introduced to geography and astronomy, subjects that later played an essential part in his career.

Family

Vespucci's immediate family was not especially prosperous but they were politically well-connected. Amerigo's grandfather, also named Amerigo Vespucci, served a total of 36 years as the chancellor of the Florentine government, known as the Signoria; and Nastagio also served in the Signoria and in other guild offices. More importantly, the Vespuccis had good relations with Lorenzo de' Medici, the powerful ruler of Florence.

Amerigo's two elder brothers, Antonio and Girolamo, were sent to study at the University of Pisa; Antonio became a notary like his father, while Girolamo entered the Church and joined the Knights Hospitaller in Rhodes.

Early career

Amerigo worked for a time with his father and continued his studies in science. In 1482, when his father died, Amerigo went to work for Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici. Amerigo served first as a household manager and then gradually took on increasing responsibilities, handling various business dealings for the family both at home and abroad. Meanwhile, he continued to show an interest in geography, at one point buying an expensive map made by the master cartographer Gabriel de Vallseca.

Seville

By 1492 Vespucci had settled permanently in Seville. It is not clear why he left Florence. In Seville, Vespucci married a Spanish woman, Maria Cerezo. Very little is known about her; Vespucci's will refers to her as the daughter of celebrated military leader Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba.

Vespucci letters

The evidence for Vespucci's voyages consists of a handful of letters attributed to him. Two of these letters were published during his lifetime and received widespread attention throughout Europe. Several scholars now believe that Vespucci did not write the two published letters in the form in which they circulated during his lifetime. They suggest that they were fabrications based in part on genuine Vespucci letters.

- Mundus Novus (1503) was a letter written to Vespucci's former schoolmate and one-time patron, Lorenzo di Pierfrancesco de' Medici. Originally published in Latin, the letter described his voyage to Brazil in 1501–1502 serving under the Portuguese flag. The document proved to be extremely popular throughout Europe. Within a year of publication, twelve editions were printed including translations into Italian, French, German, Dutch and other languages. By 1550, at least 50 editions had been issued.

- Letter to Soderini (1505) was a letter addressed to Piero di Tommaso Soderini, the leader of the Florentine Republic. It was written in Italian and published in Florence around 1505. It is more sensational in tone than the other letters and the only one to assert that Vespucci made four voyages of exploration. The authorship and the veracity of the letter have been widely questioned by modern historians. Nevertheless, this document was the original inspiration for naming the American continent in honour of Amerigo Vespucci.

The remaining documents were unpublished manuscripts; handwritten letters uncovered by researchers more than 250 years after Vespucci's death. After years of controversy, the authenticity of the three complete letters was convincingly demonstrated by Alberto Magnaghi in 1924. Most historians now accept them as the work of Vespucci but aspects of the accounts are still disputed.

- Letter from Seville (1500) describes a voyage made in 1499–1500 while in the service of Spain. It was first published in 1745 by Angelo Maria Bandini.

- Letter from Cape Verde (1501) was written in Cape Verde at the outset of a voyage undertaken for Portugal in 1501–1502. It was first published by Count Baldelli Boni in 1807. It describes the first leg of the journey from Lisbon to Cape Verde and provides details about Pedro Cabral's voyage to India which were obtained when the two fleets met by chance while anchored in the harbour at Cape Verde.

- Letter from Lisbon (1502) is essentially a continuation of the letter started in Cape Verde. It describes the remainder of a voyage made on behalf of Portugal in 1501–1502. The letter was first published by Francesco Bartolozzi in 1789.

- Ridolfi Fragment (1502) is part of a letter attributed to Vespucci but some of its assertions remain controversial. It was first published in 1937 by Roberto Ridolfi. The letter appears to be an argumentative response to questions or objections raised by the unknown recipient. A reference is made to three voyages made by Vespucci, two on behalf of Spain and one for Portugal.

Voyages and alleged voyages

The number of Vespucci's voyages, their routes, and his role and accomplishments have long been a subject of debate.

Alleged voyage of 1497–1498

This is the most controversial of Vespucci's voyages. The only known evidence of its occurrence is a letter dated 1504. The document is addressed to Florentine official Piero Soderini. According to it, Vespucci departed from Spain on 10 May 1497, and returned on 15 October 1498.

The inconsistencies in the narrative, especially regarding the route of the voyage, make some scholars believe that the letter is a forgery and that the voyage had never taken place. It is possible that Vespucci intentionally provided a made-up account of the expedition using observations from his later voyages to position himself as the first European in the New World to encounter the mainland.

Some historians have suggested that Vespucci is not the author of the letter. They think it was written by someone who had access to the navigator's private letters to Lorenzo de' Medici about his 1499 and 1501 expeditions to the Americas, which make no mention of a 1497 voyage.

Voyage of 1499–1500

In 1499, Vespucci joined a Spanish expedition led by Alonso de Ojeda as fleet commander and Juan de la Cosa as chief navigator. Their mission was to explore the coast of a new landmass found by Columbus on his third voyage and in particular investigate a rich source of pearls that Columbus had reported. Vespucci and his patrons financed two of the four ships in the small fleet. His role on the voyage is not clear. Writing later about his experience, Vespucci gave the impression that he had a leadership role, but that is unlikely, due to his inexperience. Instead, he may have served as a commercial representative on behalf of the fleet's investors. Years later, Ojeda recalled that "Morigo Vespuche" was one of his pilots on the expedition.

The vessels left Spain on 18 May 1499 and stopped first in the Canary Islands before reaching South America somewhere near present-day Suriname or French Guiana. From there the fleet split up: Ojeda proceeded northwest toward modern Venezuela with two ships, while the other pair headed south with Vespucci aboard. The only record of the southbound journey comes from Vespucci himself. He assumed they were on the coast of Asia and hoped by heading south they would, according to the Greek geographer Ptolemy reach the Indian Ocean. They passed two huge rivers (the Amazon and the Para) which poured freshwater 25 miles (40 km) out to sea. They continued south for another 40 leagues (about 150 mi or 240 km) before encountering a very strong adverse current which they could not overcome. Forced to turn around, the ships headed north, retracing their course to the original landfall. From there Vespucci continued up the South American coast to the Gulf of Paria and along the shore of what is now Venezuela. At some point they may have rejoined Ojeda but the evidence is unclear. In the late summer, they decided to head north for the Spanish colony at Hispaniola in the West Indies to resupply and repair their ships before heading home. After Hispaniola they made a brief slave raid in the Bahamas, capturing 232 natives, and then returned to Spain.

Voyage of 1501–1502

In 1501, Manuel I of Portugal commissioned an expedition to investigate a landmass far to the west in the Atlantic Ocean encountered unexpectedly by a wayward Pedro Álvares Cabral on his voyage around Africa to India. That land would eventually become present-day Brazil. The king wanted to know the extent of this new discovery and determine where it lay in relation to the line established by the Treaty of Tordesillas. Any land that lay to the east of the line could be claimed by Portugal. Vespucci's reputation as an explorer and navigator had already reached Portugal, and he was hired by the king to serve as pilot under the command of Gonçalo Coelho.

Coelho's fleet of three ships left Lisbon in May 1501. Before crossing the Atlantic they resupplied at Cape Verde. Coelho left Cape Verde in June, and from this point Vespucci's account is the only surviving record of their explorations. On 17 August 1501 the expedition reached Brazil at a latitude of about 6° south. Upon landing it encountered a hostile band of natives who killed one of its crewmen. Sailing south along the coast they found friendlier natives and were able to engage in some minor trading. At 23° S they found a bay which they named Rio de Janeiro because it was 1 January 1502. On 13 February 1502, they left the coast to return home. Vespucci estimated their latitude at 32° S but experts now estimate they were closer to 25° S. Their homeward journey is unclear since Vespucci left a confusing record of astronomical observations and distances travelled.

Alleged voyage of 1503–1504

In 1503, Vespucci may have participated in a second expedition for the Portuguese crown, again exploring the east coast of Brazil. There is evidence that a voyage was led by Coelho at about this time but it is impossible to say whether Vespucci took part. The only source for this last voyage is the Soderini letter; but several modern scholars dispute Vespucci's authorship of that letter and it is uncertain whether Vespucci undertook this trip.

Later years and death

By early 1505, Vespucci was back in Seville. His reputation as an explorer and navigator continued to grow and his recent service in Portugal did not seem to damage his standing with King Ferdinand. On the contrary, the king was likely interested in learning about the possibility of a western passage to India. In February, he was summoned by the king to consult on matters of navigation. During the next few months he received payments from the crown for his services and in April he was declared by royal proclamation a citizen of Castile and León.

From 1505 until his death in 1512, Vespucci remained in service to the Spanish crown. He continued his work as a chandler, supplying ships bound for the Indies. He was also hired to captain a ship as part of a fleet bound for the "spice islands" but the planned voyage never took place. In March 1508, he was named chief pilot for the Casa de Contratación or House of Commerce which served as a central trading house for Spain's overseas possessions. He was paid an annual salary of 50,000 maravedis with an extra 25,000 for expenses. In his new role, Vespucci was responsible for ensuring that ships' pilots were adequately trained and licensed before sailing to the New World. He was also charged with compiling a "model map" based on input from pilots who were obligated to share what they learned after each voyage.

Vespucci wrote his will in April 1511. He left most of his modest estate, including five household slaves, to his wife. His clothes, books, and navigational equipment were left to his nephew Giovanni Vespucci. He requested to be buried in a Franciscan habit in his wife's family tomb. Vespucci died on 22 February 1512, at the age of 57.

Upon his death, Vespucci's wife was awarded an annual pension of 10,000 maravedis to be deducted from the salary of the successor chief pilot. His nephew Giovanni was hired into the Casa de Contratación where he spent his subsequent years spying on behalf of the Florentine state.

Naming of America

Vespucci's voyages became widely known in Europe after two accounts attributed to him were published between 1503 and 1505. In 1506, the Soderini letter (1505) came to the attention of a group of French humanist scholars, who surmised that Vespucci had discovered a new continent.

In April 1507, Matthias Ringmann and Martin Waldseemüller published their Introduction to Cosmography with an accompanying world map. The Introduction was written in Latin and included a Latin translation of the Soderini letter. In a preface to the Letter, Ringmann wrote

I see no reason why anyone could properly disapprove of a name derived from that of Amerigo, the discoverer, a man of sagacious genius. A suitable form would be Amerige, meaning Land of Amerigo, or America, since Europe and Asia have received women's names.

A thousand copies of the world map were printed with the title Universal Geography According to the Tradition of Ptolemy and the Contributions of Amerigo Vespucci and Others. It was decorated with prominent portraits of Ptolemy and Vespucci and, for the first time, the name America was applied to a map of the New World.

The Introduction and map were a great success and four editions were printed in the first year alone. The map was widely used in universities and was influential among cartographers who admired the craftsmanship that went into its creation. In the following years, other maps were printed that often incorporated the name America. In 1538, Gerardus Mercator used America to name both the North and South continents on his influential map. By this point the name had been securely fixed on the New World.

Many supporters of Columbus felt that Vespucci had stolen an honour that rightfully belonged to Columbus. Most historians now believe that he was unaware of Waldseemüller's map before his death in 1512 and many assert that he was not even the author of the Soderini letter.

Legacy

Vespucci is better known for his letters (whether or not he wrote them all) than for his discoveries. The naming of America after him is an example of the immense role he played in the exploration of the New World and in making the European public aware of the newly discovered continents.

See also

In Spanish: Américo Vespucio para niños

In Spanish: Américo Vespucio para niños