Benedict Arnold facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Benedict Arnold V

|

|

|---|---|

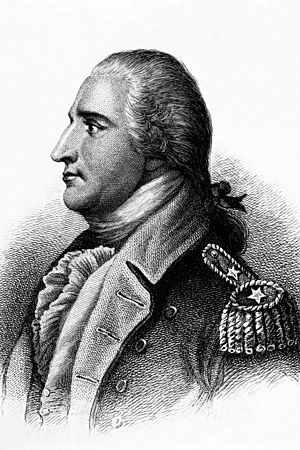

Benedict Arnold

Engraving by H.B. Hall after John Trumbull |

|

| Place of burial | |

| Service/ |

Colonial militia Continental Army British Army |

| Years of service | Colonial militia: 1757, 1775 Continental Army: 1775–1780 British Army: 1780–1781 |

| Rank | Major General (Continental Army) Brigadier General (British Army) |

| Commands held | Fort Ticonderoga (June 1775) Quebec City (siege, January–April 1776) Montreal (April–June 1776) Lake Champlain fleet (August–October 1776) Philadelphia (June 1778–April 1780) West Point (August–September 1780) American Legion (a Loyalist regiment, September 1780–1781) |

| Battles/wars | American Revolutionary War |

| Awards | Boot Monument |

| Signature | |

Benedict Arnold V (14 January 1741 [O.S. 3 January 1740] – 14 June 1801) was a general during the American Revolutionary War. He began the war in the Continental Army but later changed to the British Army.

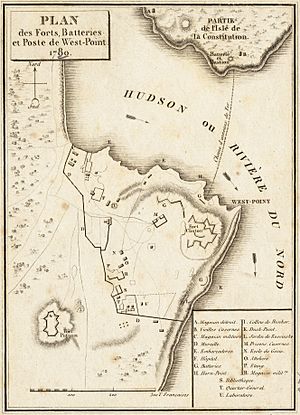

While on the American side he became commander of the fort at West Point, New York, and plotted to surrender it to the British forces. After the plot was exposed in September 1780, he was made a brigadier general in the British Army.

Born in Connecticut, Arnold was a merchant operating ships on the Atlantic Ocean when the war broke out in 1775. After joining the growing army outside Boston, he distinguished himself through acts of cunning and bravery. His actions included:

- the Capture of Fort Ticonderoga (1775)

- defensive and delaying tactics after losing the Battle of Valcour Island on Lake Champlain (1776)

- the Battle of Ridgefield, Connecticut (when was promoted to major general)

- relieving the Siege of Fort Stanwix

- actions in the Battles of Saratoga (1777), in which he suffered leg injuries that ended his combat career for several years

Arnold was passed over for promotion by the Continental Congress while other officers claimed credit for some of his accomplishments.

Frustrated and bitter, Arnold decided to change sides in 1779, and opened secret negotiations with the British. In July 1780, he asked for, and got, command of West Point in order to surrender it to the British. Arnold's scheme was exposed when American forces captured British Major John André carrying papers that revealed the plot. Upon learning of André's capture, Arnold fled down the Hudson River to the British ship HMS Vulture. He was almost captured by the forces of George Washington, who had been alerted to the plot.

Arnold got a commission as a brigadier general in the British Army, an annual pension of £360, and a lump sum of over £6,000.

He led British forces on raids in Virginia, and against New London and Groton, Connecticut, before the war effectively ended with the American victory at Yorktown.

In the winter of 1782, Arnold moved to London with his second wife, Margaret "Peggy" Shippen Arnold. He was well received by King George III and the Tories but frowned upon by the Whigs.

In 1787, he entered into mercantile business with his sons Richard and Henry in Saint John, New Brunswick, but returned to London to settle permanently in 1791, where he died ten years later.

Because of the way he changed sides, his name quickly became a byword in the United States for treason or betrayal.

Contents

Early life

Benedict was born the second of six children to Benedict Arnold III (1683–1761) and Hannah Waterman King in Norwich, Connecticut, on January 14, 1741. He was named after his great-grandfather Benedict Arnold, an early governor of the Colony of Rhode Island, and his brother Benedict IV, who died in infancy. Through his maternal grandmother, Arnold was a descendant of John Lothropp, an ancestor of at least four U.S. presidents.

When he was ten, Arnold was sent to a private school in nearby Canterbury, and was expected to go to Yale but couldn't afford it. He got an apprenticeship at a successful apothecary and general merchandise trade in Norwich. His apprenticeship with the Lathrops lasted seven years.

In 1757, when he was sixteen, he enlisted in the militia, which marched off toward Albany and Lake George. The French had besieged Fort William Henry, and their Indian allies had committed atrocities after their victory. Word of the siege's disastrous outcome led the company to turn around; Arnold served for 13 days.

Arnold's mother, to whom he was very close, died in 1759. His father's drank too much and was worse after the death of his wife, so Benedict took on the responsibility of supporting his father and younger sister. His father died in 1761.

Businessman

Helped by the Lathrops, Arnold set himself up as a pharmacist and bookseller in New Haven, Connecticut in 1762.

In 1764 he formed a partnership with Adam Babcock, another young New Haven merchant. Using the profits from the sale of his homestead they bought three trading ships and started trading with the West Indies.

The Sugar Act of 1764 and the Stamp Act of 1765 limited trade in the colonies. This led him to join the Sons of Liberty, a secret organization that was not afraid to use violence to oppose unpopular Parliamentary measures. He continued to trade as if the Stamp Act did not exist. This meant he was a smuggler in defiance of the act. Arnold also faced financial ruin.

On 22 February 1767, he married Margaret Mansfield. Their first son, Benedict VI, was born the following year, and was followed by brothers Richard in 1769, and Henry in 1772.

Margaret died early in the revolution, on 19 June 1775, while Arnold was still at Fort Ticonderoga.

Arnold was in the West Indies when the Boston Massacre took place on 5 March 1770.

Early Revolutionary War

Arnold began the war when he was elected as a captain in Connecticut's militia in March 1775. After the start of fighting at Lexington and Concord the following month, his company marched northeast to help at the siege of Boston that followed.

Arnold told the Massachusetts Committee of Safety of his idea to seize Fort Ticonderoga in New York, which he knew was poorly defended. They made him a colonel on 3 May 1775, and he immediately rode off to the west, arriving at Castleton in the disputed New Hampshire Grants (present-day Vermont) in time to join with Ethan Allen and his men in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga.

He followed up that action with a bold raid on Fort Saint-Jean on the Richelieu River north of Lake Champlain. When a Connecticut militia force arrived at Ticonderoga in June, he had a dispute with its commander over control of the fort, and resigned his Massachusetts commission. He was on his way home from Ticonderoga when he learned that his wife died earlier in June.

When the Second Continental Congress authorized an invasion of Quebec, in part on the urging of Arnold, he was passed over for command of the expedition.

Arnold then went to Cambridge, Massachusetts, and suggested to George Washington a second expedition to attack Quebec City via a wilderness route through present-day Maine. This expedition, for which Arnold received a colonel's commission in the Continental Army, left Cambridge in September 1775 with 1,100 men. After a difficult passage in which 300 men turned back and another 200 died en route, Arnold arrived before Quebec City in November. Joined by Richard Montgomery's small army, he took part in the assault on Quebec City on 31 December, in which Montgomery was killed and Arnold's leg was shattered. Rev. Samuel Spring, his chaplain, carried him to the makeshift hospital at the Hotel Dieu. Arnold, who was promoted to brigadier general for his role in reaching Quebec, maintained an ineffectual siege of the city until he was replaced by Major General David Wooster in April 1776.

Arnold then traveled to Montreal, where he served as military commander of the city until forced to retreat by an advancing British army that had arrived at Quebec in May. He commanded the rear of the Continental Army during its retreat from Saint-Jean. James Wilkinson said Arnold was the last person to leave before the British arrived.

He then directed the construction of a fleet to defend Lake Champlain, which was defeated in the October 1776 Battle of Valcour Island. His actions at Saint-Jean and Valcour Island played a notable role in delaying the British advance against Ticonderoga until 1777.

During these actions, Arnold made a number of friends and a larger number of enemies within the army power structure and in Congress.

Saratoga and Philadelphia

General Washington sent Arnold to the defend Rhode Island after the British seized Newport in December 1776, where the militia was too poorly equipped to even consider an attack on the British.

Arnold was near his home, so he took the opportunity to visit his children.

In February 1777, he learned that he had been passed over for promotion to major general by Congress. Washington refused his offer to resign, and wrote to members of Congress in an attempt to correct this, noting that "two or three other very good officers" might be lost if they persisted in making politically-motivated promotions.

Arnold was on his way to Philadelphia to discuss his future when he was alerted that a British force was marching toward a supply depot in Danbury, Connecticut. Along with David Wooster and Connecticut militia General Gold Selleck Silliman he organized the militia response. In the Battle of Ridgefield, he led a small contingent of militia attempting to stop or slow the British return to the coast, and was again wounded in his left leg.

Arnold went on to Philadelphia, where he met with members of Congress about his rank. His action at Ridgefield, coupled with the death of Wooster due to wounds sustained in the action, resulted in Arnold's promotion to major general, although his seniority was not restored over those who had been promoted before him. Amid negotiations over that issue, Arnold wrote out a letter of resignation on 11 July the same day word arrived in Philadelphia that Fort Ticonderoga had fallen to the British. Washington refused his resignation and ordered him north to assist with the defense there.

Arnold arrived in Schuyler's camp at Fort Edward, New York on 24 July. On 13 August Schuyler dispatched him with a force of 900 to relieve the siege of Fort Stanwix, where he used a trick to end the siege. Arnold had an Indian messenger sent into the camp of British Brigadier General Barry St. Leger with news that the approaching force was much larger and closer than it actually was; this convinced St. Leger's Indian support to abandon him, forcing him to give up the effort.

Arnold then returned to the Hudson, where General Gates had taken over command of the American army, which had by then retreated to a camp south of Stillwater. He then distinguished himself in both Battles of Saratoga, even though General Gates, following a series of escalating disagreements and disputes that culminated in a shouting match, removed him from field command after the first battle.

During the fighting in the second battle, Arnold, against Gates' orders, took to the battlefield and led attacks on the British defenses. He was again severely wounded in the left leg late in the fighting. Arnold himself said it would have been better had it been in the chest instead of the leg.

Burgoyne surrendered ten days after the second battle, on 17 October 1777. In response to Arnold's valor at Saratoga, Congress restored his command seniority. However, Arnold interpreted the manner in which they did so as an act of sympathy for his wounds, and not an apology or recognition that they were righting a wrong.

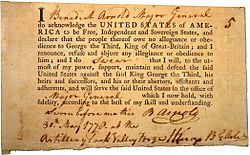

Arnold spent several months recovering from his injuries. Rather than amputating his shattered left leg, he had it crudely set, leaving it 2 inches (5.1 cm) shorter than the right. He returned to the army at Valley Forge in May 1778 to the applause of men who had served under him at Saratoga. There he took part in the first recorded Oath of Allegiance along with many other soldiers, as a sign of loyalty to the United States.

Arnold made the Masters-Penn mansion, as it was then called, his headquarters while military commander of Philadelphia. It later served as the presidential mansion of George Washington and John Adams, 1790–1800.

After the British withdrew from Philadelphia in June 1778 Washington appointed Arnold military commander of the city.

Even before the Americans reoccupied Philadelphia, Arnold began planning to capitalize financially on the change in power there, engaging in a variety of business deals designed to profit from war-related supply movements and benefiting from the protection of his authority.

Arnold lived extravagantly in Philadelphia. During the summer of 1778 Arnold met Peggy Shippen, the 18-year-old daughter of Judge Edward Shippen, a Loyalist sympathizer who had done business with the British while they occupied the city. Peggy had been courted by British Major John André during the British occupation of Philadelphia. Peggy and Arnold married on 8 April 1779. Peggy and her circle of friends had found methods of staying in contact with the British across the battle lines, in spite of military bans on communication with the enemy.

Plotting to change sides

Sometime early in May 1779, Arnold met with Stansbury. Stansbury said that, after meeting with Arnold, "I went secretly to New York with a tender of [Arnold's] services to Sir Henry Clinton." Ignoring instructions from Arnold not to involve anyone else in the plot, Stansbury crossed the British lines and went to see Jonathan Odell in New York. Odell was a Loyalist working with William Franklin, the last Colonial Governor of New Jersey and the son of Benjamin Franklin. On 9 May Franklin introduced Stansbury to Major André, who had just been named the British spy chief.

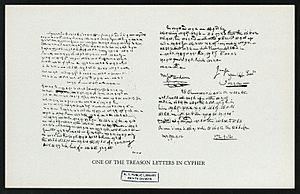

This was the beginning of a secret correspondence between Arnold and André, sometimes using his wife Peggy as well for passing messages between them.

Secret communications

André spoke to General Clinton, who gave him broad authority to pursue Arnold's offer. André then drafted instructions to Stansbury and Arnold.

This first letter opened a discussion on the types of assistance and intelligence Arnold might provide, and included instructions for how to communicate in the future. Letters would be passed through the women's circle that Peggy Arnold was a part of, but only Peggy would be aware that some letters contained instructions written in both code and invisible ink that were to be passed on to André, using Stansbury as the courier.

By July 1779, Arnold was providing the British with troop locations and strengths, as well as the locations of supply depots, all the while discussing what money he should get for this. At first, he asked for £10,000, an amount the Continental Congress had given Charles Lee for his services in the Continental Army. By October 1779, the discussions had ground to a halt. Furthermore, Patriot mobs were scouring Philadelphia for Loyalists, and Arnold and the Shippen family were being threatened. Arnold was rebuffed by Congress and by local authorities in requests for security details for himself and his in-laws.

Court martial

The court martial to consider the charges against Arnold began meeting on 1 June 1779, but was delayed until December 1779 by General Clinton's capture of Stony Point, New York. Arnold was cleared of all but two minor charges on 26 January 1780. Arnold worked over the next few months to publicize this fact; however, in early April, just one week after Washington congratulated Arnold on the 19 May birth of his son, Edward Shippen Arnold, Washington published a formal rebuke of Arnold's behavior.

The Commander-in-Chief would have been much happier in an occasion of bestowing commendations on an officer who had rendered such distinguished services to his country as Major General Arnold; but in the present case, a sense of duty and a regard to candor oblige him to declare that he considers his conduct [in the convicted actions] as imprudent and improper.

– Notice published by George Washington, 6 April 1780

Shortly after Washington's rebuke, a Congressional inquiry into his expenditures concluded that Arnold had failed to fully account for his expenditures incurred during the Quebec invasion, and that he owed the Congress some £1,000, largely because he was unable to document them. A significant number of these documents were lost during the retreat from Quebec; angry and frustrated, Arnold resigned his military command of Philadelphia in late April.

Offer to surrender West Point

Early in April, Philip Schuyler had approached Arnold with the possibility of giving him the command at West Point. Arnold reopened the secret channels with the British, informing them of Schuyler's proposals and including Schuyler's assessment of conditions and West Point. He also provided information on a proposed French-American invasion of Quebec that was to go up the Connecticut River. (Arnold did not know that this proposed invasion was trick intended to divert British resources.)

On 16 June Arnold inspected West Point while on his way home to Connecticut to take care of personal business, and sent a highly detailed report through the secret channel. When he reached Connecticut Arnold arranged to sell his home there, and began transferring assets to London through intermediaries in New York. By early July he was back in Philadelphia, where he wrote another secret message to Clinton on 7 July which implied that his appointment to West Point was assured and that he might even provide a "drawing of the works ... by which you might take [West Point] without loss".

General Clinton and Major André, who returned victorious from the Siege of Charleston on 18 June were immediately caught up in this news. Clinton, concerned that Washington's army and the French fleet would join in Rhode Island, again fixed on West Point as a strategic point to capture. André, who had spies and informers keeping track of Arnold, verified his movements. Excited by the prospects, Clinton informed his superiors of his intelligence coups, but failed to respond to Arnold's 7 July letter.

In a letter of 11 July, Arnold complained that the British did not appear to trust him, and threatened to break off negotiations unless progress was made. On 12 July he wrote again, making explicit the offer to surrender West Point, although his price (in addition to indemnification for his losses) rose to £20,000, with a £1,000 down payment to be delivered with the response. These letters were delivered not by Stansbury but by Samuel Wallis, another Philadelphia businessman who spied for the British.

Command at West Point

On 3 August 1780, Arnold obtained command of West Point. On 15 August he received a coded letter from André with Clinton's final offer: £20,000, and no indemnification for his losses. Due to difficulties in getting the messages across the lines, neither side knew for some days that the other was in agreement to that offer. Arnold's letters continued to detail Washington's troop movements and provide information about French reinforcements that were being organized. On 25 August Peggy finally delivered to him Clinton's agreement to the terms.

Washington, in assigning Arnold to the command at West Point, also gave him authority over the entire American-controlled Hudson River, from Albany down to the British lines outside New York City. While en route to West Point, Arnold renewed an acquaintance with Joshua Hett Smith, someone Arnold knew had done spy work for both sides, and who owned a house near the western bank of the Hudson just south of West Point.

Once he established himself at West Point, Arnold began systematically weakening its defenses and military strength. Needed repairs on the chain across the Hudson were never ordered. Troops were liberally distributed within Arnold's command area (but only minimally at West Point itself), or furnished to Washington on request. He also peppered Washington with complaints about the lack of supplies, writing, "Everything is wanting". At the same time, he tried to drain West Point's supplies, so that a siege would be more likely to succeed. His subordinates, some of whom were long-time associates, grumbled about unnecessary distribution of supplies, and eventually concluded that Arnold was selling some of the supplies on the black market for personal gain.

On August 30, Arnold sent a letter accepting Clinton's terms and proposing a meeting to André through yet another intermediary: William Heron, a member of the Connecticut Assembly he thought he could trust. Heron, in a comic twist, went into New York unaware of the significance of the letter, and offered his own services to the British as a spy. He then took the letter back to Connecticut, where, suspicious of Arnold's actions, he delivered it to the head of the Connecticut militia.

General Parsons, seeing a letter written as a coded business discussion, laid it aside. Four days later, Arnold sent a ciphered letter with similar content into New York through the services of a prisoner-of-war's wife. Eventually, a meeting was set for 11 September near Dobb's Ferry. This meeting was thwarted when British gunboats in the river, not having been informed of his impending arrival, fired on his boat.

Plot exposed

Arnold and André finally met on 21 September at Joshua Hett Smith's house. On the morning of 22 September James Livingston, the colonel in charge of the outpost at Verplanck's Point, fired on HMS Vulture, the ship that was intended to carry André back to New York. This action damaged the ship and she had to retreat downriver, forcing André to return to New York overland. Arnold wrote out passes for André so that he would be able to pass through the lines, and also gave him plans for West Point.

On Saturday, 23 September André was captured, near Tarrytown, by three Westchester patriots named John Paulding, Isaac Van Wart and David Williams; the papers exposing the plot to capture West Point were found and sent to Washington, and Arnold's treachery came to light after Washington examined them.

Arnold learned of André's capture the following morning, 24 September, when he received Jameson's message that André was in his custody and that the papers André was carrying had been sent to General Washington. Arnold received Jameson's letter while waiting for Washington, with whom he had planned to have breakfast. He made all haste to the shore and ordered bargemen to row him downriver to where the Vulture was anchored, which then took him to New York.

From the ship Arnold wrote a letter to Washington, requesting that Peggy be given safe passage to her family in Philadelphia, a request Washington granted.

When presented with evidence of Arnold's betrayal, it is reported that Washington was calm. He did, however, investigate the extent of the betrayal, and suggested in negotiations with General Clinton over the fate of Major André that he was willing to exchange André for Arnold. This suggestion Clinton refused; after a military tribunal, André was hanged at Tappan, New York on 2 October. Washington also infiltrated men into New York in an attempt to kidnap Arnold; this plan, which very nearly succeeded, failed when Arnold changed living quarters prior to sailing for Virginia in December.

Arnold attempted to justify his actions in an open letter titled To the Inhabitants of America, published in newspapers in October 1780. In the letter to Washington requesting safe passage for Peggy, he wrote that "Love to my country actuates my present conduct, however it may appear inconsistent to the world, who very seldom judge right of any man's actions."

After switching sides

British Army service

The British gave Arnold a brigadier general's commission with an annual income of several hundred pounds, but only paid him £6,315 plus an annual pension of £360 because his plot failed.

In December 1780, under orders from Clinton, Arnold led a force of 1,600 troops into Virginia, where he captured Richmond by surprise and then went on a rampage through Virginia, destroying supply houses, foundries, and mills. This activity brought Virginia's militia out, and Arnold eventually retreated to Portsmouth to either be evacuated or reinforced. The pursuing American army included the Marquis de Lafayette, who was under orders from Washington to summarily hang Arnold if he was captured.

Reinforcements led by William Phillips (who served under Burgoyne at Saratoga) arrived in late March, and Phillips led further raids across Virginia, including a defeat of Baron von Steuben at Petersburg, until his death of fever on 12 May 1781.

Arnold commanded the army only until 20 May when Lord Cornwallis arrived with the southern army and took over. Cornwallis ignored advice given by Arnold to locate a permanent base away from the coast that might have averted his later surrender at Yorktown.

On his return to New York in June, Arnold made a variety of proposals for continuing to attack essentially economic targets in order to force the Americans to end the war. Clinton, however, was not interested in most of Arnold's aggressive ideas, but finally relented and authorized Arnold to raid the port of New London, Connecticut.

On 4 September not long after the birth of his and Peggy's second son, Arnold's force of over 1,700 men raided and burned New London and captured Fort Griswold, causing damage estimated at $500,000. British casualties were high — nearly one quarter of the force was killed or wounded, a rate at which Clinton claimed he couldn't afford.

Even before Cornwallis's surrender in October, Arnold had requested permission from Clinton to go to England to give Lord Germain his thoughts on the war in person. When word of the surrender reached New York, Arnold renewed the request, which Clinton then granted.

On 8 December 1781, Arnold and his family left New York for England. In London he aligned himself with the Tories, advising Germain and King George III to renew the fight against the Americans. In the House of Commons, Edmund Burke expressed the hope that the government would not put Arnold "at the head of a part of a British army" lest "the sentiments of true honor, which every British officer [holds] dearer than life, should be afflicted."

Arnold then applied to accompany General Carleton, who was going to New York to replace Clinton as commander-in-chief; this request went nowhere. Other attempts to gain positions within the government or the British East India Company over the next few years all failed, and he was forced to subsist on the reduced pay of non-wartime service.

His reputation also came under criticism in the British press, especially when compared to that of Major André, who was celebrated for his patriotism.

New business opportunities

In 1785 Arnold and his son Richard moved to Saint John, New Brunswick, where they speculated in land, and established a business doing trade with the West Indies.

Arnold purchased large tracts of land in the Maugerville area, and acquired city lots in Saint John and Fredericton.

Arnold returned to London in 1786 to bring his family to Saint John. The family moved to Saint John in 1787, where Arnold created an uproar with a series of bad business deals and petty lawsuits. Following the most serious, a slander suit he won against a former business partner, townspeople burned him in effigy in front of his house as Peggy and the children watched. The family left Saint John to return to London in December 1791.

In July 1792 he fought a bloodless duel with the James Maitland, 8th Earl of Lauderdale after the Earl impugned his honor in the House of Lords.

With the outbreak of the French Revolution Arnold outfitted a privateer, while continuing to do business in the West Indies, even though the hostilities increased the risk.

He was imprisoned by French authorities on Guadeloupe amid accusations of spying for the British, and narrowly eluded hanging by escaping to the blockading British fleet after bribing his guards.

He helped organize militia forces on British-held islands, receiving praise from the landowners for his efforts on their behalf. This work, which he hoped would earn him wider respect and a new command, instead earned him and his sons a land grant of 15,000 acres (6,100 ha) in Upper Canada, near present-day Renfrew, Ontario.

Death

In January 1801 Arnold's health began to decline. He died after four days of delirium, on 14 June 1801, at the age of 60.

Arnold was buried at St. Mary's Church, Battersea in London, England. His funeral procession had "seven mourning coaches and four state carriages"; the funeral was without military honors.

He left a small estate, reduced in size by his debts, which Peggy cleared by selling household items. Among his bequests were considerable gifts to one John Sage, who turned out to be a his son.

Family

During his marriage to Margaret Mansfield, Arnold had the following children:

- Benedict Arnold VI (1768–1795) (captain in the British Army, killed in action)

- Richard Arnold (1769–1847)

- Henry Arnold (1772–1826)

and with Peggy Shippen, he raised a family active in British military service:

- Edward Shippen Arnold (1780–1813) (lieutenant)

- James Robertson Arnold (1781–1854) (lieutenant general)

- George Arnold (1787–1828) (lieutenant colonel)

- Sophia Matilda Arnold (1785–1828)

- William Fitch Arnold (1794–1846) (captain)

Tributes

On the battlefield at Saratoga, now preserved in Saratoga National Historical Park, stands a monument in memorial to Arnold, but there is no mention of his name on the engraving. Donated by Civil War General John Watts DePeyster, the inscription on the Boot Monument reads: "In memory of the most brilliant soldier of the Continental army, who was desperately wounded on this spot, winning for his countrymen the decisive battle of the American Revolution, and for himself the rank of Major General." The victory monument at Saratoga has four niches, three of which are occupied by statues of Generals Gates, Schuyler, and Morgan. The fourth niche is empty.

On the grounds of the United States Military Academy at West Point there are plaques commemorating all of the generals that served in the Revolution. One plaque bears only a rank, "major general" and a date, "born 1740", and no name.

The house at 62 Gloucester Place where Arnold lived in central London still stands, bearing a plaque that describes Arnold as an "American Patriot". The church where Arnold was buried, St. Mary's Church, Battersea, England, has a commemorative stained-glass window which was added between 1976 and 1982. The faculty club at the University of New Brunswick, Fredericton, has a Benedict Arnold Room, in which framed original letters written by Arnold hang on the walls.

Interesting facts about Benedict Arnold

- He was the most infamous traitor in US history.

- Within the United States, calling someone a “Benidict Arnold” means you are calling them a traitor.

- Benedict Arnold's second wife Peggy Shippen helped him conspire and was the highest-paid spy in the American Revolution.

- At the beginning of the Revolution he was a hero.

Images for kids

-

An 1865 political cartoon depicting Benedict Arnold and Jefferson Davis in hell

See also

In Spanish: Benedict Arnold para niños

In Spanish: Benedict Arnold para niños