Civil War Defenses of Washington facts for kids

|

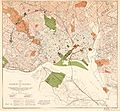

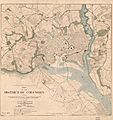

Civil War Fort Sites

|

|

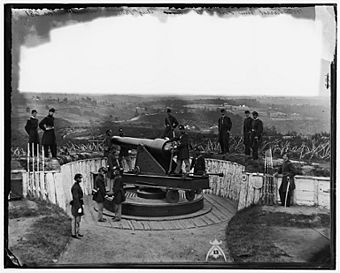

Fort Totten

|

|

| Location | Washington, D.C. Fairfax County, Virginia Prince George's County, Maryland |

|---|---|

| NRHP reference No. | 74000274 (original) 78003439 (increase) |

Quick facts for kids Significant dates |

|

| Added to NRHP | July 15, 1974 |

| Boundary increase | September 13, 1978 |

The Civil War Defenses of Washington were a group of Union Army fortifications that protected the federal capital city, Washington, D.C., from invasion by the Confederate States Army during the American Civil War (see Washington, D.C., in the American Civil War). The sites of some of these fortifications are within a collection of National Park Service (NPS) properties that the National Register of Historic Places identifies as the Fort Circle. The sites of other such fortifications in the area have become parts of state, county or city parks or are located on privately owned properties. A trail connecting the sites is part of the Potomac Heritage Trail.

Parts of the earthworks of some such fortifications still exist. Other such fortifications have been completely demolished.

History

The Washington area had 68 major enclosed forts, as well as 93 prepared (but unarmed) batteries for field guns, and seven blockhouses surrounding it during the American Civil War. There were also twenty miles of rifle pits and thirty miles of connecting military roads.' These were Union forts, and the Confederacy never captured one. Indeed, most never came under enemy fire. These were used to house soldiers and store artillery and other supplies.

List of Historic Forts

The following forts are listed in the National Register of Historic Places nomination form.

- Battery Kemble Park 38°55′49.4″N 77°05′46.8″W / 38.930389°N 77.096333°W

- Fort Bayard 38°57′18.7″N 77°05′29.4″W / 38.955194°N 77.091500°W

- Fort Reno Park 38°57′10.2″N 77°04′41.9″W / 38.952833°N 77.078306°W

- Fort De Russy 38°57′48.7″N 77°03′04.1″W / 38.963528°N 77.051139°W

- Fort Stevens 38°57′50.2″N 77°01′46″W / 38.963944°N 77.02944°W

- Fort Slocum 38°57′36.7″N 77°00′38.9″W / 38.960194°N 77.010806°W

- Fort Totten 38°56′51.8″N 77°00′18.5″W / 38.947722°N 77.005139°W

- Fort Bunker Hill 38°56′06.7″N 76°59′04.8″W / 38.935194°N 76.984667°W

- Fort Lincoln 38°55′31″N 76°57′04″W / 38.92528°N 76.95111°W

- Fort Mahan 38°53′42.6″N 76°56′41.6″W / 38.895167°N 76.944889°W

- Fort Chaplin 38°53′19″N 76°56′34″W / 38.88861°N 76.94278°W

- Fort Dupont Park 38°52′22.1″N 76°56′26.3″W / 38.872806°N 76.940639°W

- Fort Davis 38°51′59.6″N 76°57′06.7″W / 38.866556°N 76.951861°W

- Fort Ricketts 38°51′24.5″N 76°58′32.8″W / 38.856806°N 76.975778°W

- Fort Stanton 38°51′29.5″N 76°58′54.9″W / 38.858194°N 76.981917°W

- Fort Carroll 38°50′16.4″N 77°00′24.7″W / 38.837889°N 77.006861°W

- Fort Greble 38°49′32.8″N 77°00′55.8″W / 38.825778°N 77.015500°W

- Fort Foote (MD) 38°46′0.1″N 77°01′40.1″W / 38.766694°N 77.027806°W

- Fort Marcy Park (VA) 38°56′2.4″N 77°07′33.6″W / 38.934000°N 77.126000°W

Other Forts

- Battery Garesche

- Battery Rodgers

- Fort Albany

- Fort C. F. Smith

- Fort Corcoran

- Fort Craig

- Fort Ellsworth

- Fort Ethan Allen

- Fort Jackson

- Fort Kearny

- Fort Lyon

- Fort Myer

- Fort O'Rourke

- Fort Ramsay

- Fort Reynolds

- Fort Richardson

- Fort Runyon

- Fort Scott

- Fort Sumner

- Fort Tillinghast

- Fort Ward

- Fort Willard

- Fort Williams

- Fort Woodbury

- Fort Worth

Development of "Fort Circle"

In 1919 the Commissioners of the District of Columbia pushed Congress to pass a bill to consolidate the aging forts into a "Fort Circle" system of parks that would ring the growing city of Washington. As envisioned by the Commissioners, the Fort Circle would be a green ring of parks outside the city, owned by the government, and connected by a "Fort Drive" road in order to allow Washington's citizens to easily escape the confines of the capital. However, the bill allowing for the purchase of the former forts, which had been turned back over to private ownership after the war, failed to pass both the House of Representatives and Senate.

Despite that failure, in 1925 a similar bill passed both the House and Senate, which allowed for the creation of the National Capital Parks Commission (NCPC) to oversee the construction of a Fort Circle of parks similar to that proposed in 1919. The NCPC was authorized to begin purchasing land occupied by the old forts, much of which had been turned over to private ownership following the war. Records indicate that the site of Fort Stanton was purchased for a total of $56,000 in 1926. The duty of purchasing land and constructing the fort parks changed hands several times throughout the 1920s and 1930s, eventually culminating with the Department of the Interior and the National Park Service taking control of the project in the 1940s.

During the Great Depression, crews from the Civilian Conservation Corps embarked on projects to improve and maintain the parks, which were still under the control of District authority at that time. At Fort Stanton, CCC members trimmed trees and cleared brush, as well as maintaining and constructing park buildings. Various non-park buildings were also discussed for the land. The City Department of Education proposed building a school on park land, while authorities from the local water utility suggested the construction of a water tower would be suitable for the tall hills of the park. The Second World War interrupted these plans, and post-war budget cuts instituted by President Harry S. Truman postponed the construction of the Fort Drive once more. Though land for the parks had mostly been purchased, construction of the ring road connecting them was pushed back again and again. Other projects managed to find funding, however. In 1949, President Truman approved a supplemental appropriation request of $175,000 to construct "a swimming pool and associated facilities" at Fort Stanton Park.

By 1963, when President John F. Kennedy began pushing Congress to finally build the Fort Circle Drive, many in Washington and the National Park Service were openly questioning whether the plan had outgrown its usefulness. After all, by this time, Washington had grown past the ring of forts that had protected it a century earlier, and city surface roads already connected the parks, albeit not in as linear a route as envisioned. The plan to link the fort parks via a grand drive was quietly dropped in the years that followed.

Images for kids

-

Remains of the earthworks connecting Fort O'Rourke and Fort Farnsworth, still visible in the Huntington area of Fairfax County.