Edward Alsworth Ross facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

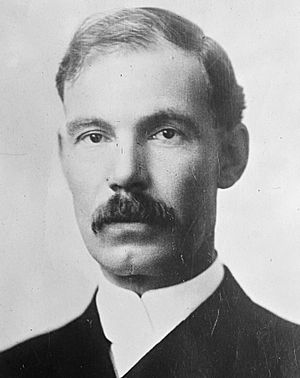

Edward Alsworth Ross

|

|

|---|---|

From the George Grantham Bain Collection (Library of Congress)

|

|

| Born |

Edward Alsworth Ross

December 12, 1866 Virden, Illinois, US

|

| Died | July 22, 1951 (aged 84) |

| Known for |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Sociology |

| Doctoral advisor | Richard T. Ely |

| Doctoral students | C. Wright Mills |

Edward Alsworth Ross (December 12, 1866 – July 22, 1951) was a progressive American sociologist, eugenicist, economist, and major figure of early criminology.

Contents

Early life

He was born in Virden, Illinois. His father was a farmer. He attended Coe College and graduated in 1887. After two years as an instructor at a business school, the Fort Dodge Commercial Institute, he went to Germany for graduate study at the University of Berlin. He returned to the U.S., and in 1891 he received his PhD from Johns Hopkins University in political economy under Richard T. Ely, with minors in philosophy and ethics.

Ross was a professor at Indiana University (1891–1892), secretary of the American Economic Association (1892), professor at Cornell University (1892–1893), and professor at Stanford University (1893–1900). He was then a professor at University of Nebraska (1900-1904) and University of Wisconsin-Madison (1905-1937).

In the field of economics, he made contributions to the study of taxation, debt management, value theory, uncertainty, and location theory.

Ross affair and departure from Stanford

In Stanford's "first academic freedom controversy", Ross was fired from Stanford because of his political views on eugenics. He objected to Chinese and Japanese immigrant labor. He expressed his wish to restrict entry of other races in public speeches and Japanese immigration altogether. In the speech that was the catalyst for his potential firing and ultimate resignation, he was quoted as declaring, "And should the worst come to the worst it would be better for us if we were to turn our guns upon every vessel bringing Japanese to our shores rather than to permit them to land." In response, Jane Stanford called for his resignation.

In Ross' public statement as to his resignation, he wrote that his friend David Starr Jordan had asked him to make the speech. Jordan managed to keep Ross from being fired, but Ross resigned shortly after. The position was at odds with the university's founding family, the Stanfords, who had made their fortune in Western rail construction, a major employer of coolie laborers.

Ross had also made critical remarks about the railroad industry in his classes: "A railroad deal is a railroad steal." This was too much for Jane Stanford, Leland Stanford's widow, who was on the board of trustees of the university. Numerous professors at Stanford resigned after protests of his dismissal, sparking "a national debate... concerning the freedom of expression and control of universities by private interests." The American Association of University Professors was founded largely in response to this incident.

Nebraska, Wisconsin, and later life

Ross left for the University of Nebraska, where he taught until 1905. In 1906, he moved to the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where he became Professor of Sociology, and eventually chairman of the department. He retired in 1937.

His understanding of Americanization and assimilation bore a striking resemblance to that of another Wisconsin professor, Frederick Jackson Turner. Like Turner, Ross believed that American identity was forged in the crucible of the wilderness. The 1890 census's proclamation that the frontier had disappeared, then, posed a significant threat to America's ability to assimilate the mass of immigrants who were arriving from southern and eastern Europe. In 1897, just four years after Turner had presented his frontier thesis to the American Historical Association, Ross, then at Stanford, argued that the loss of the frontier destroyed the machinery of the melting pot process.

In 1913, the State of Wisconsin passed its first sterilization law. Ross, who lived in Wisconsin at the time, was a reserved proponent of sterilization and indicated his support for the measure. He qualified his support by contrasting it with the greater harm of hanging a man and advocated its initial use "only to extreme cases, where the commitments and the record pile up an overwhelming case." Involuntary sterilization remained legal in Wisconsin until July 1978.

Ross visited Russia after the Bolshevik Revolution in 1917. He endorsed the revolution even as he acknowledged its bloody origins. He was subsequently a leading advocate of US recognition of the Soviet Union. However, he later served on the Dewey Commission, which cleared Leon Trotsky of the charges made against him by the Soviet government during the Moscow Trials.

From 1900 to the 1920s, Ross supported the alcohol Prohibition movement as well as continuing to support eugenics and immigration restriction. By 1930, he had moved away from those views, however.

In the 1930s, he was a supporter of the New Deal programs of President Franklin Roosevelt. In 1940, he became chairman of the national committee of the American Civil Liberties Union, serving until 1950.

He died in 1951.

Works

- Sin and Society: An Analysis of Latter-Day Iniquity (with a letter from President Roosevelt), Houghton, Mifflin & Company, 1907.

- Social Psychology: An Outline and Source Book, The Macmillan Company, 1908.

- The Changing Chinese: The Conflict of Oriental and Western Cultures in China, The Century Co., 1911.

- South of Panama, The Century Co., 1915.

- What is America?, The Century Co., 1919.

- The Outlines of Sociology, The Century Co., 1923.

- The Russian Soviet Republic, The Century Co., 1923.

- The Social Revolution in Mexico, The Century Co., 1923.

- Roads to Social Peace, The University of North Carolina Press, 1924.

- Report on the Employment of Native Labor in Portuguese Africa, Abbott Press, 1925.

- Standing Room Only?, The Century Co., 1927.

- Tests and Challenges in Sociology, The Century Co., 1931.

- Seventy Years of It: An Autobiography, D. Appleton-Century Company, 1936.

- La libertad en el Mundo Moderno, In: Letras (Lima), Vol. 2, Iss. 5, 1936. Doi: https://doi.org/10.30920/letras.2.5.3

- New-Age Sociology, D. Appleton-Century Company, 1940.

Selected articles

- "Christianity in China," The Century Magazine, March 1911.

- "The Middle West," The Century Magazine, February/April 1912.

- "American and Immigrant Blood," The Century Magazine, December 1913.

- "Immigrant in Politics," The Century Magazine, January 1914.

- "Origins of the American People," The Century Magazine, March 1914.

- "The Celtic Tide," The Century Magazine, April 1914.

- "The Menace of Migrating Peoples," The Century Magazine, May 1921.

- "The United States of India," The Century Magazine, December 1925.

- "The Man-Stifled Orient," The Century Magazine, July 1927.

- "Dulling the Scythes of Azrael," The Century Magazine, August 1927.

- "The Old Woman Who Lived In a Shoe," The Century Magazine, September 1927.

- "Population Pressure and War," Scribner's Magazine, September 1927.

Miscellany

- Schweinitz Brunner, Edmund de (1923). Churches of Distinction in Town and Country, with a Foreword by Edward Alsworth Ross, George H. Doran Company.

See also

- American Committee for the Defense of Leon Trotsky