Eiji Tsuburaya facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

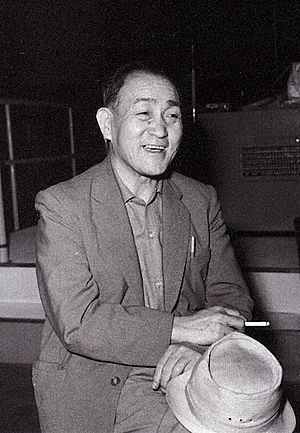

Eiji Tsuburaya

|

|

|---|---|

| 円谷 英二 | |

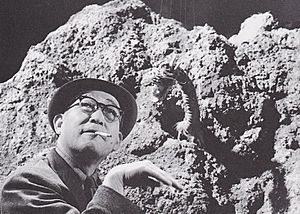

Tsuburaya in 1959

|

|

| Born |

Eiichi Tsumuraya

July 7, 1901 Sukagawa, Fukushima, Empire of Japan

|

| Died | January 25, 1970 (aged 68) Itō, Shizuoka, Japan

|

| Resting place | Catholic Fuchū Cemetery |

| Alma mater | Tokyo Kanda Electrical Engineering School |

| Occupation |

|

| Years active | 1919–1969 |

|

Works

|

Filmography |

| Spouse(s) |

Masano Araki

(m. 1930; |

| Children | 4, including Hajime and Noboru |

| Relatives | Aōdō Denzen (ancestor) Hiroshi Tsuburaya (grandson) |

| Awards | 6 Japan Technical Awards |

| Signature | |

|

|

Eiji Tsuburaya (Japanese: 円谷 英二, Hepburn: Tsuburaya Eiji, July 7, 1901 – January 25, 1970) was a Japanese special effects director, filmmaker and inventor. He is regarded as one of the most influential figures in the history of the Japanese cinema and a creator of the Godzilla and Ultraman franchises. Known as the "Father of Tokusatsu", he pioneered Japan's special effects industry, introducing several technological developments in film productions. During his five-decade career, Tsuburaya worked on approximately 250 films and earned six Japan Technical Awards.

Following a brief stint as an inventor, Tsuburaya was employed by Japanese cinema pioneer Yoshirō Edamasa in 1919 and began his career working as an assistant cinematographer on Edamasa's A Tune of Pity. Thereafter, he worked as an assistant cinematographer on several films, notably Teinosuke Kinugasa's A Page of Madness. At the age of thirty-two, Tsuburaya watched King Kong, which greatly influenced him to work in special effects. In 1935, he worked on the film Princess Kaguya, one of Japan's first major films to incorporate special effects. His first majorly successful film in effects, The Daughter of the Samurai (1937), remarkably featured the first full-scale rear projection.

In 1937, Tsuburaya was employed by Toho and established the company's effects department. Tsuburaya directed the effects for The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya in 1942, which became the highest-grossing Japanese film in history upon its release. His groundbreaking effects were believed to be behind the film's major success, and he won an award for his work from the Japan Motion Picture Cinematographers Association. In 1948, however, Tsuburaya left Toho and created Tsuburaya Special Technology Laboratory with his eldest son Hajime. Thus, he worked at major Japanese studios outside Toho, creating effects for films such as Daiei's The Invisible Man Appears (1949).

In 1950, Tsuburaya officially returned to Toho alongside his effects crew from Tsuburaya Visual Effects Laboratories. At age fifty-three, he gained international recognition and won his first Japan Technical Award for Special Skill for directing the effects in Ishirō Honda's kaiju film Godzilla (1954). He served as the special effects director for Toho's string of financially successful science fiction films that followed, including, Rodan (1956), The Mysterians (1957), Mothra, The Last War (both 1961), King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962), and Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964). King Kong vs. Godzilla became the second-highest-grossing Japanese film in history upon its release and rebooted the Godzilla series, which is regarded as the longest-running film franchise of all time. In April 1963, Tsuburaya founded Tsuburaya Special Effects Productions; his company would go onto produce the television shows Ultra Q, Ultraman (both 1966), Ultraseven (1967–1968), and Mighty Jack (1968). Ultra Q and Ultraman were extremely successful upon their 1966 broadcast, with the former making him a household name in Japan and gaining him more attention from the media who dubbed him the "God of Tokusatsu". In the same period, he was also credited for working on Honda's Japanese-American co-productions The War of the Gargantuas (1966) and King Kong Escapes (1967), as well as the kaiju epic Destroy All Monsters (1968). While he spent his late years working on several Toho films and operating his company, Tsuburaya's health began to decline, and he died of a heart attack in January 1970.

Contents

Biography

Childhood to war years: 1901–1945

Childhood and youth (1901–1919)

Eiji Tsuburaya was born Eiichi Tsumuraya (圓谷 英一, Tsumuraya Eiichi) on July 7, 1901 at the merchant house called Ōtsukaya in Sukagawa, Iwase, Fukushima Prefecture, where his family ran a malted rice business. He was the first son of Isamu Shiraishi and Sei Tsumuraya, with a large extended family. When he was three, his mother died of illness, at the age of 19, shortly after giving birth to her second son. His father subsequently left the family, and Tsuburaya was raised by his grandmother Natsu. Through Natsu, he was related to the Edo period painter Aōdō Denzen, who brought copper printing and Western painting to Japan, from whom Tsuburaya considered to have inherited his dexterity. His uncle Ichirō, who was Sei's younger brother, was five years older than him and acted like an elder brother to him. Thus, Tsuburaya began to use the nickname Eiji ("ji" indicating second-born) instead of Eiichi ("ichi" indicating first-born).

He attended the Dai'ichi Jinjo Koto Elementary School in Sukagawa beginning in 1908 and it was soon realized he had a talent for drawing. Though he often daydreamed of flying during his elementary school years, Tsuburaya was interested in regular studies. Consequently, his aunt, Yoshi, predicted he would become prosperous by the age of thirty-three. In 1910, Tsuburaya took an interest in flight due to the sensational success of Japanese aviators. Two years after, he took advantage of a photograph featured in a newspaper article and started building model airplanes as a hobby, an interest he would pursue throughout his life.

He saw his first film the ensuing year, which featured footage of a volcanic eruption on Sakurajima; strangely, Tsuburaya was more fascinated by the projector than the movie itself. In 1958, Tsuburaya told Kinema Junpo that because he was extremely fascinated by the projector, he purchased a "toy movie viewer" and created his own film strips by "carefully cutting rolled paper, then making sprocket holes, and drawing stick figures [on the paper], frame by frame." Because of his craftwork at a young age, he became a provincial celebrity and was interviewed by the Fukushima Minyu Shimbun.

In 1915, at the age of 14, he graduated the equivalent of high school, and begged his family to let him enroll in the Nippon Flying School at Haneda. After the school was closed on account of the accidental death of its founder, Seitaro Tamai, in 1917, Tsuburaya attended the Tokyo Kanda Electrical Engineering School (now Tokyo Denki University). While at the school, he became an inventor at the toy company Utsumi and created some successful products that are still widely used in the 21st century. His devised inventions at the company include the first battery-powered phone capable of making calls, an automatic speed photo box, an "automatic skate" and the toy phone. The latter two earned him a patent fee of ¥500.

Early career and marriage (1919–1934)

In the spring of 1919, filmmaker Yoshirō Edamasa employed Tsuburaya at his company Natural Color Motion Pictures Company (dubbed "Tenkatsu"). Tsuburaya worked as Edamasa's camera assistant on films such as A Tune of Pity (1919) and Tombs of the Island (1920) and reportedly also served as a screenwriter during this period. Despite Tenkatsu becoming part of the Kokatsu Company and Edamasa leaving his job in March 1920, Tsuburaya maintained working at the studio until he was ordered to serve the Imperial Japanese Army in December 1922.

After leaving the army in 1923, Tsuburaya moved back to his family's house in Sukagawa. He stayed there considering possible future paths within the filmmaking industry until departing one morning on an unknown date, leaving a note: "I won't return home until I succeed in the motion picture business, even if I die trying." The next year, he work as the cinematographer on the film The Hunchback of Enmei'in Temple. Tsuburaya joined Shochiku the following year and would have his breakthrough as the cameraman, and assistant director on Teinosuke Kinugasa's masterpiece, A Page of Madness (1926). In 1927, he shoot Minoru Inuzuka's jidaigeki films Children's Swordplay and Melee both starring Chōjirō Hayashi and Tsuyako Okajima, as well as Toko Yamazaki's The Bat Copybook, Mad Blade Under the Moon, and Record of the Tragic Swords of the Tenpo Era. Because of the financial success of these films, Tsuburaya became regarded as one of the Kyoto's leading cinematographers.

In 1928, while working on eleven films at Shochiku, Tsuburaya began creating and utilizing developing camera operating techniques, including double-exposure and slow-motion camerawork. The next year, he constructed his own smaller version of D. W. Griffith's considerable 140-foot tall six-wheeled shooting crane, which he used both in and outside of the studio. Having invented it without the benefit of using blueprints or manuals, the wooden crane allowed Tsuburaya to improve camera movement and was able to be used in and outside the studio. The creation proved a success until one day while Tsuburaya and an assistant prepared the crane to film a scene, it collapsed sending him plummeting to the ground of the studio. A witness of the incident named Masano Araki was one of the first to run to his aid. She visited Tsuburaya daily while he was in the infirmary and the pair formed a relationship shortly thereafter. On February 27, 1930, Tsuburaya married the decade-younger Araki. Their first child, Hajime, was born on April 23 the following year.

In May 1932, Tsuburaya, Akira Mimura, Hiroshi Sakai, Kohei Sugiyama, Masao Tamai, and Tadayuki Yokota established the Japan Cameraman Association, which later coalesced with other companies to become the Nippon Cinematographers Club (presently called the Japanese Society of Cinematographers). Shortly after that, the association would start to hold award ceremonies. In November of that year, Tsuburaya quit Shochiku and joined Nikkatsu Futosou Studios. Around the same time, he began using the professional name "Eiji Tsuburaya".

In 1933, Tsuburaya saw the groundbreaking American film King Kong, which inspired him to work on films featuring special effects. In 1962, Tsuburaya told the Mainichi Shimbun that he attempted to convince Nikkatsu to "import this technical know-how, but they had little interest in it because at the time, I was seen as merely a cameraman who worked on Kazuo Hasegawa's historical dramas." He managed to acquire a 35mm print of the film and started to study its special effects frame-by-frame without the advantage of documents explaining how they were produced. In October 1933, an article on the film's effect, written by Tsuburaya, was published in Photo Times, which featured an inaccurate understanding of how the scenes were created.

In the same year, Masano gave birth to a second child, a daughter named Miyako. In 1935, she would, however, die of a confidential cause that shocked her parents. Nevertheless, Tsuburaya continued with his customary life, working on several projects, and arranging methods to enhance his camerawork.

In December of 1933, Nikkatsu granted Tsuburaya permission to use and study new screen projection technology for the company's jidaigeki films. While the studio approved of his decision to project these films cast into a location use using location plates, not all of his technological developments were met with approval. During filming the final scenes for Asataro Descends Mt. Akagi in February 1934, Tsuburaya got into a significant disagreement with Nikkatsu's CEO, who had no acquaintance with what Tsuburaya was creating and assumed Tsuburaya was wasting the company's money. After the argument, Tsuburaya resigned from his job at Nikkatsu.

J.O. Studios, directorial works, and Toho (1934–1940)

Shortly after leaving Nikkatsu, he accepted an offer from Kyoto entrepreneur Yoshio Osawa to work at his company, J.O. Talkies, and research optical printing and screen projection. In October 1934, Tsuburaya and his colleagues completed the first iron shooting crane model and used it to shoot Atsuo Tomioka's The Chorus of a Million. Contrary to his previous prototype, this one was on a truck that operated on tracks, which made it able to change the camera's position in seconds. Osawa renamed the studio J.O. Studios and designated Tsuburaya as its chief cinematographer in December of that year.

From February to August of 1935, he traveled to Hawaii, the Philippines, Australia, and New Zealand on the cruiser Asama in order to shoot his directorial debut, Three Thousand Miles Across the Equator, a feature-length propaganda documentary film. During the expedition, his second son, Noboru was born on May 10 that year.

Upon returning from the voyage, Tsuburaya began work on Princess Kaguya, an adaptation of the 10th-century Japanese literary tale The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter. He not only served as the film's cinematographer but was also in charge of special effects for the first time. For the film, he worked with animator Kenzō Masaoka to create miniatures, puppets, a composite of Kaguya emerging from a cut bamboo plant, and a sequence in which a ship encounters a storm. While the original print of the film is considered lost, a shortened version screened in England in 1936 was discovered by a researcher at the British Film Institute in May 2015. The shortened version was released in Japan as part of an event marking Tsuburaya's 120th birthday on September 4 and 5, 2021.

In March of the next year, his histrionic directorial debut, Folk Song Collection: Oichi of Torioi Village, was theatrically released. It is an adventure film concerning a condemned romance, which features political tones. Folk Song Collection: Oichi of Torioi Village was the second film to star popular geisha singer Ichimaru and it also featured actor Kenji Susukida. Soon after its completion, Tsuburaya began working on Arnold Fanck's The Daughter of the Samurai (released 1937). The Daughter of the Samurai was the first German-Japanese co-production, Tsuburaya's first major success in effects, and it featured the first full-scale rear projection. The German staff were impressed by his elaborate miniature work on the project.

In September 1936, Ichizō Kobayashi merged the film studios P.C.L. Studios and P.C.L. Film Company with J.O. Studios to create the film and theatre production company Toho. Film producer Iwao Mori was made the production manager at Toho and was keenly aware of the importance of special effects during a tour of Hollywood. As a result, in 1937, Mori hired Tsuburaya at the company's Tokyo Studio, establishing the special effects department on November 27, 1937, and treating him as the section's manager. Shortly after, Tsuburaya received a research budget and began studying optical printers to create Japan's first version of the device, which he designed.

Among Tsuburaya's first film assignments at Toho were The Abe Clan, a jidaigeki film directed by Hisatora Kumagai, and the unreleased propaganda musical The Song of Major Nanjo (both 1938). The latter film was directed and shot by Tsuburaya, and he completed it on September 6 of that year.

In 1939, because of an instruction from the Imperial government, he joined the Kumagaya Aviation Academy of the Imperial Army Corps and was entrusted to shoot flight-training films. After impressing his superiors with his aerial photography, Tsuburaya was given more assignments and a master's certificate during his almost three years at the academy.

In November 1939, while Tsuburaya was still at the flight school and undertaking assignments at Toho, he was appointed head of Toho's Special Arts Department. A month after that, he was commissioned to shoot a science film for Toho's then-recently assembled educational section. Under governance demands, Toho was mandated to maintain the creation of propaganda films. Accordingly, in May 1940, Tsuburaya began directing the documentary The Imperial Way of Japan for Toho Education Films' branch Toho National Policy Film Association. He also filmed the effects of Sotoji Kimura's Navy Bomber Squadron, featuring the bombing scene with a miniature airplane for the first time in his career, and he was given his first credit for special effects. Navy Bomber Squadron was believed lost for over sixty years until an unfinished copy of the film was discovered and screened in 2006.

In September 1940, Yutaka Abe's The Burning Sky, was released to Japanese cinemas. Tsuburaya was in charge of effects for the film and received his first accolade from the Japan Motion Picture Cinematographers Association. His next undertaking, Son Gokū, was released on November 6, 1940. In the August 1960 issue of American Cinematographer, he is quoted saying that for Son Gokū: "I was called upon to create and photograph a monkey-like monster which was supposed to fly through the air", adding: "I managed the job with some success and this assignment set the pattern for my future work."

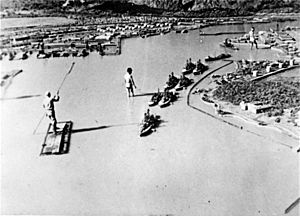

War years (1941–1945)

On December 7, 1941, the Japanese attacked the United States navy base on Pearl Harbor, causing a sensation of national pride in Japan. Consequently, the Imperial Japanese Government tasked Toho to produce a film that would influence the nation to believe they would win the Pacific War. The resulting film, Kajirō Yamamoto's war epic The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya (1942), became the highest-grossing Japanese film in history upon its release in December 1942 and won Kinema Junpo's Best Film Award. Tsuburaya directed its effects, which he created with the assistance of navy-provided photographs of the Pearl Harbor attack, and he worked with future Godzilla collaborates Akira Watanabe and Teizō Toshimitsu for the first time. His groundbreaking effects work was supposedly behind the film's major success and accordingly, he won the Technical Research Award from the Japan Motion Picture Cinematographers Association. The film depicted the attack so realistically that footage from it was later featured in documentaries on the Pearl Harbor attack.

Around the same time as The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya was in production, Toho's effects department was filming Japan's first puppet film Ramayana. The film's screenplay, inspired by the Sanskrit epic of the same name, was written by future Moonlight Mask creator Kōhan Kawauchi the previous year under Tsuburaya's supervision.

Tsuburaya's next major productions were all war films. During the production of General Kato's Falcon Fighters (released in 1944), Tsuburaya had his first meeting with his future collaborator, filmmaker Ishirō Honda. After watching The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya, Honda became interested in special effects and believed Tsuburaya's work in General Kato's Falcon Fighters was inferior in scope, but the art and gunpowder technology had enhanced. Additionally, Tsuburaya expressed dissatisfaction with the size of the shooting stage, the art materials, the method of performance, etc.

Shortly before Toho distributed General Kato's Falcon Fighters in cinemas, Masano and Tsuburaya's third son and last child, Akira, was born on February 12, 1944. Akira was the first of the couple's sons to receive baptism since his mother had been converted to the Catholic Church by her younger sister. Masano persisted in introducing her children to Catholicism and ultimately converted her husband.

In late 1945, Tsuburaya made the effects in Torajirō Saitō's Five Men from Tokyo, for which he was credited as Eiichi Tsuburaya. Five Men from Tokyo is a comedy film concerning five men who struggle to make a living after returning to Tokyo after the war and remain unemployed due to the Tokyo air raids on March 10, 1945 at the end of World War II. During the two-hour-long attacks on March 10, Tsuburaya told his sons fairy tales to keep them quiet as the family was in their residence's bomb shelter.

Occupation years to Chūshingura: 1946–1962

Early postwar work (1946–1954)

Even though Toho was unaffected by the Tokyo bombings as the company was located in Seijo, the amount of film productions was reduced due to the Occupation of Japan. Because of this, the company produced only eighteen films in 1946, with Tsuburaya working on eight of them. Since he and his effects unit at the company had a minor slate of films to work on, Tsuburaya began testing matte painting and optical printing. While the effects sector of Toho was experimenting with this equipment, meanwhile, the company was struggling.

Toho was on the verge of disbandment due to the three major labor disputes that occurred at the studio during the late 1940s. According to Akira Tsuburaya, for his father to get to work he had to sneak around the Japanese police and U.S. tanks deployed during these strikes and disputes. To repel the police, the labor strikers erected a barricade, using a large fan made by the special effects department of the company that was equipped with the Zero fighter engine that Tsuburaya had used during the war. These events lead to the creation of Shintoho; Tsuburaya would create the effects for Shintoho's first film, A Thousand and One Nights with Toho (1947).

In late March 1948, Tsuburaya was purged from Toho by the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers because of his comprehensive miniatures featured in The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya. Therefore, Toho disbanded their special effects division and Tsuburaya, with his son Hajime, founded the independent special effects company Tsuburaya Special Technology Laboratory, an unofficial juridical entity. Henceforth, he worked at major film studios outside Toho.

In 1949, five major Daiei Film productions featuring effects directed by Tsuburaya were released to Japanese theaters: Japanese horror filmmaker Bin Kato's The White Haired Fiend, Keigo Kimura's Flowers of Raccoon Palace, Kiyohiko Ushihara's The Rainbow Man, Akira Nobuchi's The Ghost Train, and Nobuo Adachi's The Invisible Man Appears. The Invisible Man Appears made a significant contribution as the first substantial Japanese science fiction film and the country's first adaption of H. G. Wells' novel The Invisible Man. Created by studying the eponymous 1933 film adaptation of Wells' novel, Daiei had intended this film to be Tsuburaya's full-scale postwar recovery, featuring special effects superior to those in Universal Pictures' The Invisible Man film series. Tsuburaya, however, was disappointed with his lack of competence on the project and gave up his ambition to become a Daiei employee after The Invisible Man Appears was finished.

In 1950, Tsuburaya relocated Tsuburaya Special Technology Laboratory to Toho; his independent company was merely the size of six tatami mats inside Toho Studios. While slowly rebuilding the company's Special Arts Department, he filmed all of the title cards, trailers, and the logo for Toho's films from 1950 to 1954. The first production featuring contributions by Tsuburaya upon his return to Toho was reportedly a 1950 film directed by Hiroshi Inagaki based on the life of Japanese swordsman Sasaki Kojirō. However, Senkichi Taniguchi's anti-war film Escape at Dawn is sometimes cited as featuring his contributions.

In February 1952, Tsuburaya's exile from public office was officially lifted. That same month, Ishirō Honda's second feature film, The Skin of the South, was released to theaters. Tsuburaya directed the film's effects for the typhoon and landslide scenes, which was his first experience acting as the effects director on a film by the future Godzilla director. Tsuburaya collaborated with Honda and producer Tomoyuki Tanaka on The Man Who Came to Port later that year, which marked the first time the trio, who are considered the creators of Godzilla, collaborated.

During World War II, Toho began researching 3D films and completed a 3D film process known as "Tovision". While it was later abandoned, the "Tovision" project at Toho was later revived when the 3D film Bwana Devil (1952) became a box office hit in the United States. Hence, the company produced its first 3D film, future Godzilla co-writer Takeo Murata's The Sunday That Jumped Out (1953). It features cinematography by Tsuburaya, who shot this short film using an interlocking camera.

After the completion of The Sunday That Jumped Out, Murata discussed creating a tokusatsu film about a giant whale attacking Tokyo, which Tsuburaya devised the previous year. Tsuburaya, therefore, resubmitted the conception of this production to producer Iwao Mori. Although this project never materialized, elements of it were inserted into early drafts of Godzilla the following year.

Tsuburaya's next project, the war epic Eagle of the Pacific (1953), was his first significant partnership with Ishirō Honda. As the film featured many effects sequences from The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya, Tsuburaya used only a small crew to shot its new effects. Upon its release, the film reportedly became Toho's first postwar production to gross over ¥100 million ($278,000). The ensuing year, he and Honda collaborated on another war film, Farewell Rabaul, released to Japanese theaters in February 1954, to moderate box office success. His effects for this assignment were more advanced than in Eagle of the Pacific, featuring many more of his technological approaches and syntheses. Because of the success of Eagle of the Pacific and Farewell Rabaul, Tomoyuki Tanaka believed Tsuburaya should make more tokusatsu (special effects) films with Honda. Tsuburaya's next film would become Japan's first global hit and gain him international attention.

International recognition (1954–1959)

After failing to renegotiate with the Indonesian government for the production of In the Shadow of Glory, producer Tomoyuki Tanaka began to consider creating a giant monster (or kaiju) film, inspired by Eugène Lourié's The Beast from 20,000 Fathoms (1953) and the Daigo Fukuryū Maru incident. He believed that it would be potential due to the financial success of monster films and nuclear fears generating news. Thus, he wrote an outline for the project and pitched it to Iwao Mori. Following Tsuburaya's agreement to create its effects, Mori approved the production, eventually titled Godzilla, in mid-April 1954; filmmaker Ishirō Honda soon took over the directing duties. During preproduction, Tsuburaya considered using stop motion to depict the titular monster but, as stated by special effects crew member Fumio Nakadai, had to employ the "costume method" because he "finally decided it wouldn't work". This technique is now known as "suitmation".

Tsuburya's special effects department filmed Godzilla in 71 days from August 1954 to late October on a budget of ¥27 million. He and his relatively younger crew worked relentlessly, regularly starting at 9:00 a.m., preparing at 5:00 p.m., and finishing the shoot at 4 or 5 a.m. the following morning. Shortly after Tsuburaya completed filming its effects, Tsuburaya, Tanaka, and Honda were shown the finished film on October 23, 1954, and its staff and cast were shown the film on October 25. Upon its nationwide release on November 3, Tsuburaya's effects received critical acclaim and the film became a box office hit. As a result, Godzilla established Toho as the most successful effects company in the world and Tsuburaya obtained his first Japan Technical Award for his efforts.

Instantly after completing Godzilla in October, Tsuburaya began working on another Toho-produced science fiction film, The Invisible Avenger, which was released to Japanese theaters in December 1954 under the title Invisible Man. This tokusatsu production was directed by Motoyoshi Oda and featured special effects and photography by Tsuburaya. Because The Invisible Avenger was his second film to feature an invisible character, after The Invisible Man Appears (1949), he inherited and expanded the technology used in The Invisible Man Appears for the movie. Tsuburaya instructed his crew to portray the title character's invisibility in various ways throughout the film, including optical synthesis and suggested that the character disguised his invisibility ability by dressing up as a clown.

Due to the enormous box-office success of Godzilla, Toho quickly gathered the majority of the crew behind the film to create a smaller-budget sequel to the film, entitled Godzilla Raids Again. Tsuburaya was officially given the title of special effects director for the first time on Godzilla Raids Again, as he was always credited under "special technique" beforehand. Shot in less than 3 months, the film opened in April 1955. A month after the release of Godzilla Raids Again, Tsuburaya began directing the effects of Half Human, his second kaiju film collaboration with director Ishirō Honda. Among his efforts on this film, the effects director notably created stop-motion animation, rear-screen miniature, and miniature avalanche sequences.

In April 1956, Godzilla became the first Japanese film to be widely distributed throughout the United States and it was later released worldwide, leading Tsuburaya to gain international recognition. However, for its American release, it was retitled Godzilla, King of the Monsters!, heavily re-edited, and featured new footage with actor Raymond Burr.

Tsuburaya's next major undertaking, The Legend of the White Serpent, a film adaptation of a novel by Fusao Hayashi based on the Chinese legend Legend of the White Snake, was Toho's first tokusatsu feature completely filmed in color (via Eastmancolor). In preparation for the film, which was produced on a then-enormous budget of ¥210 million, Tsuburaya and his unit spent a month training with color process technology before shooting the effects. After working on The Legend of the White Serpent, Tsuburaya made the renowned Toho logo and his unit constructed the opening credits for most of the company's films. Between working on large-scale Toho films, he created the effects for Toho's musical The Snapping Turtle, Nippon TV's Ninja Arts of Sanada Castle and theatrical productions for Tokyo Takarazuka Theater.

Toho's next assignment for Tsuburaya was Rodan, the first kaiju film produced in color. 60% of Rodan's ¥200 million budget was spent on Tsuburaya's effects, which was expended on optical animation, matte paintings, and extremely elaborate miniature sets created to be destroyed or flown over by its namesake monster (played by original Godzilla suit actor Haruo Nakajima). Rodan required a large number of model sets in a variety of sizes, including 1/10, 1/20, 1/25, and 1/30, to be developed and assembled by Tsuburaya's division. The film premiered in Japan In December 1956 and upon its release in the United States the following year, earned more at the box office than any previous science fiction film.

Throne of Blood, an adaptation of William Shakespeare's Macbeth from renowned filmmaker Akira Kurosawa, was Tsuburaya's first film release of 1957. Kurosawa cut several scenes by Tsuburaya due to his displeasure with the amount of footage he made for Throne of Blood. He next served as the special effects director for The Mysterians, a science fiction epic directed by Ishirō Honda. It was the first color Cinemascope film by Honda and Tsuburaya and is often called the "definitive science fiction movie". He obtained another Japan Technical Award for his widescreen effects in The Mysterians.

A new subgenre for Toho was born with Tsuburaya's first movie of 1958, The H-Man, which was the first entry in the "Transforming Human Series". He next directed the effects for Honda's Varan the Unbelievable about a giant monster awakened in the Tōhoku mountains that surfaces in Tokyo Bay. Initially planned as a made-for-television film co-produced between Toho and the American company AB-PT Pictures, the production was plagued with numerous difficulties. AB-PT collapsed during production, leading Toho to alter the film's status to a theatrical feature. Tsuburaya's final film released in 1958 was Kurosawa's The Hidden Fortress.

Tsuburaya began 1959 by directing the special effects for a storm sequence featured in Honda's Inao: Story of an Iron Arm, for which he also constructed the miniature for the title character's rowboat. Next, he worked on Monkey Sun, co-written and directed by Kajirō Yamamoto as an all-star remake of his 1940 film Son Gokū, on which the effects director also labored. Taking inspiration from watching soybean paste in the broth of his wife's miso soup, he created scenes with storm clouds and smoke and ash erupting from three volcanoes. His effects featured in the film were described by biographer August Ragone as "comical and surreal". Tsuburaya followed it by operating on the Tokyo Takarazuka Theater production The Story of Bali and then moved on to Shūe Matsubayashi's Submarine I-57 Will Not Surrender, his first war film in six years. In order to film submarine scenes for Matsubayashi's film, a model seabed terrain was built in the first Toho miniature pool (dubbed the "Small Pool" after a more considerable version was completed). He also filmed his effects for the film in color, but they were converted to black-and-white for the final film.

Tsuburaya's following significant production, director Hiroshi Inagaki's big-budget religious epic The Three Treasures, was created as Toho's celebratory thousandth film. Based on legends featured in the Kojiki and Nihon Shoki, it stars Toshiro Mifune as Yamato Takeru and the kami Susanoo. The effects director and his crew shot several substantial sequences included in the film such as a battle between Mifune's character Susanoo and the eight-headed dragon Yamata no Orochi and an eruption of Mount Fuji. Tsuburaya used the "Toho Versatile Process" for the first time for The Three Treasures, which he developed on a budget of ¥62 million for widescreen color films and revealed in May of the same year. It earned over ¥340 million against a ¥250 million budget, ranking as Toho's highest-grossing film of the year and the second-highest-grossing film altogether. He won the Japan Technical Award for Special Skill and was presented with the Special Achievement Award at Movie Day. While he was pleased with the film's success, Tsuburaya became disappointed after seeing a picture of the heads of the Yamata no Orochi prop held up by piano wires in a newspaper article concerning its special effects. Accordingly, he declined an interview with the newspaper because he believed the photograph "broke children's dreams".

When the Space Race erupted between the U.S. and the Soviet Union in the late 1950s, Tsuburaya counseled Toho to produce a film about a lunar expedition, believing that such a film would soon materialize. Therefore, his next film, Battle in Outer Space, was a science fiction epic about a group of astronauts who battle extraterrestrials on the surface of the moon. Tsuburaya paid homage to producer George Pal's Destination Moon (1950) in the film's moon landing sequence; he met Pal in Los Angeles in 1962. Because films featuring his contributions attained global popularity and praise for Japanese cinema, Hearst filmed Tsuburaya directing the film's effects and he received the Special Award of Merit at the 4th Movie Day ceremony prior to its release.

From The Secret of the Telegian to Chūshingura (1960–1962)

A smaller-scale science fiction film, entitled The Secret of the Telegian, which was Toho's second installment in the Transforming Human Series, marked Tsuburaya's first assignment of 1960. Tsuburaya next took on a project of a much larger extent, Storm Over the Pacific, the first-ever color war film. The "Big Pool" was created at Toho Studios and used for the first time during the production of this film. It would later be utilized in the production of virtually every Godzilla film until it was demolished after the filming of the ending of Godzilla: Final Wars. Storm Over the Pacific obtained critical acclaim upon its release and numerous of Tsuburaya's effects sequences were later be featured in Midway (1976), a film by Jack Smight that was also about the Pacific War. Throughout the rest of the year, he worked on notable productions such as the third film in the Transforming Human Series, The Human Vapor, and oversaw the creation of an extremely detailed miniature of Osaka Castle and directed its destruction scene in Hiroshi Inagaki's jidaigeki film The Story of Osaka Castle.

Next, Tsuburaya directed the effects for Mothra, another big-budget kaiju film created in collaboration with Ishirō Honda. Allegedly inspired by his dreams, Tsuburaya created the namesake titular giant divine moth kaiju, which would become one of the icons of Japanese fantasy cinema alongside Godzilla and Rodan and later appear in numerous films thereafter. Though its considerable budget allowed the effects department to create the largest-scale miniature set ever constructed for a Toho production, Tsuburaya was displeased with some sequences shot for the film, especially the scene where the powerful gusts of wind generated by Mothra's wings cause a vehicle to crash into a store window during the monster's attack on the fictional New Kirk City, and some composite cuts of the Shobijin. Nonetheless, he decided to keep these scenes upon editing Mothra in postproduction. The film opened on July 30, 1961, becoming a massive box office hit and, as stated by biographer August Ragone, an "instant classic" alongside Honda and Tsuburaya's earlier kaiju films Godzilla and Rodan. Ragone asserted that "no other kaiju eiga [sic] before or since has touched its size and magnitude", adding: "It's difficult to imagine a film like Mothra being produced today."

After directing blue screen dream scenes with actor Toshiro Mifune for Hiroshi Inagaki's film The Youth and His Amulet (1961), Tsuburaya moved on to direct the effects for Shūe Matsubayashi's ¥300 million epic tokusatsu film The Last War. The Last War emerged as a major hit upon its October 1961 release, and Tsuburaya's effects received critical acclaim. Additionally, he later listed this film as one of his "masterpieces". Producer Tomoyuki Tanaka, assured from the box office success of Mothra and The Last War, gave Honda and Tsuburaya their most considerable budget yet and 300 days to shoot Gorath, their next science fiction epic. Although Gorath is considered to feature some of his best work, it was a box office failure when it was released in March 1962.

"My movie company came up with a very interesting script that combines King Kong and Godzilla, so I couldn't help working on this production instead of my new fantasy films. This script is very special to me; it struck a deep emotional chord because it was seeing King Kong back in 1933 that sparked my interest in the world of special visual effects."

After filming Gorath, Tsuburaya began planning to work on other projects such as a new version of Princess Kaguya. However, he postponed those to direct the special effects for Honda's King Kong vs. Godzilla. Early drafts of the script were sent back with notes from the studio asking that the monster antics be made as "funny as possible". This comical approach was embraced by Tsuburaya, who wanted to appeal to children's sensibilities and broaden the genre's audience. Much of the monster battle was filmed to contain a great deal of humor but the approach was not favored by most of the effects crew, who "couldn't believe" some of the things Tsuburaya asked them to do, such as Kong and Godzilla volleying a giant boulder back and forth. According to Sadamasa Arikawa, the suit sculptors had a difficult time coming up with a King Kong suit that appeased Tsuburaya; the King Kong suits used in the final film were described by August Ragone as "less than stellar". For their portrayals, Tsuburaya gave Nakajima (playing Godzilla) and the King Kong suit actor (Shoichi Hirose) free rein to choreograph their own moves. Tsuburaya directed sequences at a miniature outdoor set on the Miura Coast that depicted the giant octopus's attack on the Faro Island village and later ate some of the four octopuses for dinner with some of the special effects crew members. During its original theatrical release in August 1962, King Kong vs. Godzilla became the second-highest-grossing Japanese film in history and was attended by 11.2 million people, leading it to be regarded as the most-attended film in the Godzilla series.

Tsuburaya's final film release of 1962 was Inagaki's epic jidaigeki film Chūshingura: Hana no Maki, Yuki no Maki, for which he and his department made forced perspective stages and various optical effects. Produced by Toho—like King Kong vs. Godzilla—in celebration of their 30th anniversary, it was Toho's fourth highest-grossing film of the year and the tenth-highest altogether.

Birth of a company to last years: 1963–1970

Birth of a company and career expansion (1963–1965)

The first film released in 1963 featuring Tsuburaya's contributions was another war film by Shūe Matsubayashi, Attack Squadron!, released in January of that year. Though not an epic like Toho's previous war movies, the film nevertheless features several miniature Japanese and American aircraft by Tsuburaya's crew, with some of the models portrayed using radio control. The sole new miniature battleship built for the film was Yamato, which was an enormous motorized model constructed at 1/15 scale and measuring 17.5 meters (or 57.5 feet).

After visiting Hollywood to observe the special effects work of major American studios, Tsuburaya founded his own independent company Tsuburaya Special Effects Productions (later called simply Tsuburaya Productions) on April 12, 1963. It was initially handled entirely by his family: Tsuburaya was reported as its director general and present, his wife (Masano) was on the director's board, and his second son (Noboru) was declared the accountant. Hajime, Tsuburaya's eldest son, would soon join the company as well, leaving his award-winning directorial employment at the Tokyo Broadcasting System. Around August of the same year, Kiyoshi Suzuki was employed as a photography assistant, and Koichi Takano, who was a news cameraman for Kyodo Television from Toho, was hired at the company as a cameraman. Tsuburaya himself employed Takano for Tsuburaya Productions' first full-scale tokusatsu production, Alone Across the Pacific (1963), which required twenty-five effects sequences. Throughout the rest of the year, Tsuburaya worked for his new company and Toho, where he still controlled the effects department despite canceling his exclusive contract with Toho.

Tsuburaya's next production, described by August Ragone as a "lighthearted World War I adventure", was entitled The Siege of Fort Bismarck. For his first partnership with director Kengo Furusawa, Tsuburaya's division developed several new models for the film, including large-scale miniatures, full-scale replications of early twentieth-century flying vehicles, and an enormous outdoor model set of Fort Bismarck. According to Ragone, Tsuburaya enjoyed working on this film but he nonetheless desired to make his own tribute feature to Japanese aviation pioneers.

Shortly after completing The Siege of Fort Bismarck in April 1963, he began preproduction work on Matango, another film created in cooperation with Ishirō Honda and is regarded as the final entry in the Transforming Human Series. In contrary to the majority of the previous Toho films featuring monsters, the actors were capable of psychical interaction with the suit actors portraying the monsters on a sound stage. Sadao Iizuka said that Tsuburaya "focused" Toho to purchase the "Optical Printer 1900 Series" in order to facilitate the effects featured in the film, noting that optical synthesis technology became popular after the film's release. A box office failure upon its Japanese release, it was not included in Kinema Junpo's list of height-grossing films for the year, and has been since anointed "virtually unknown film", except to "aficionados of Asian cult cinema, fans of weird literature, and sleepless consumers of late-night television programming".

Tsuburaya soon moved on to film miniatures and produce optical animation (via his newly purchased Optical Printer 1900 Series) for The Lost World of Sinbad. This film, directed by Senkichi Taniguchi from a screenplay by Mothra and King Kong vs. Godzilla writer Shinichi Sekizawa, included an acclaimed choreographed chase sequence between a wizard and a witch created via animation and matte photography that gained Tsuburaya another Japan Technical Award for Special Skill.

Tsuburaya almost immediately started work on another Honda-directed science fiction tokusatsu movie, Atragon (1963). Based on Shunrō Oshikawa's novel The Undersea Warship and incorporated with Shigeru Komatsuzaki's novel Undersea Empire, the film concerns a group of former colleges, friends, and family that must convince the captain of the battleship Gotengo, Hachiro Jinguji (played by Jun Tazaki), to use his battleship to save the world from the invading ancient undersea civilization of Mu who are using their advanced technology and guardian sea dragon Manda in an attempt to concern the surface world. Since Toho desired to distribute the film in Japanese theaters on December 22 of that year, Tsuburaya was given roughly two months to shoot the effects sequences for Atragon. Thus, in order to achieve the company's goal, he separated his special effects team into two units, assuring that it would allow him to complete the assignment as soon as possible. Four miniatures were constructed to represent the Gotengo, with the largest, a ¥1.5 million radio-operated model, measuring 4.5 meters (15 feet) in length. Although it was quickly converted and developed, the film is regarded as "one of the cornerstones of Japanese cinema" and is still often referenced in media.

Since this was the peak of his career, Tsuburaya was concluding model effects for the Hiroshi Inagaki-directed jidaigeki film Whirlwind and Atragon simultaneously. As both Inagaki and Tsuburaya were busy producing other films, they never directly discussed how the threatening tornado in an effects sequence for Whirlwind would appear onscreen. Fortunately, both had the same opinion on the direction of materialization. During this period, lack of sleep and workload-related stress were taking a toll on Tsuburaya's health, so he was often discovered sleeping in his chair during scene setups for his effects shoots.

The third installment in the Godzilla film series, Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964), was Tsuburaya's next film. Often regarded as Tsuburaya's best kaiju film, it was produced in celebration of the tenth-anniversary of Toho's kaiju films and depicts the battle between Godzilla and the title character of the self-titled 1961 film Mothra (as suggested by its title). He utilized his 1900 optical printer to remove damages in composite photography shots for the picture and to create Godzilla's atomic breath. Tsuburaya went on location to shoot some composite plates of Nagoya Castle for the scene where Godzilla destroyed the castle. Nakajima was, however, incapable of entirely destroying the model based on the castle and attempted to salvage the shot by having Godzilla appear enraged by the Castle's strong fortification, but Tsuburaya chose to re-shoot the scene with a rebuilt model designed to crumble more easily. He also went on location to shoot a segment featuring the United States navy discharging missiles at Godzilla for the U.S. market which was discluded from the Japanese version. This was one of the rare occasions that a sequence with Godzilla was shoot outside Toho Studios.

In the spring of 1964, Tsuburaya received a visit from frequent collaborator Ishirō Honda on the Hawaiian Island of Kauai. The effects director was shooting a dogfight and plain crash sequence for renowned singer and actor Frank Sinatra's None but the Brave (released in 1965), which was his sole directorial picture. As the first Japanese-American coproduction, this anti-war epic revolves around a troop of American soldiers stranded in the Pacific during World War II who are forced to collaborate with an opposition Japanese unit that has also been stranded on the island. During Honda's visit, Tsuburaya told him that he was planning the first Tsuburaya Productions-produced television series then-titled Unbalance but was struggling to find a lead actor for the series. Honda convinced Kenji Sahara (who played in None but the Brave and also starred in several Honda-Tsuburaya kaiju films) to play the team leader for the intended show that later became Ultra Q (1966). None but the Brave was released in Japan by Toho on January 15, 1965, and was distributed by Warner Bros. in the U.S. the following month, where it grossed $2.5 million and obtained mixed reviews from critics.

Tsuburaya ordered Oxberry's 1200 optical printer while in New York in January 1964, which only one other studio in the world owned at the time, Disney. Costing a then-enormous ¥40 million (equivalent to $570,710 in 2014), Tsuburaya desired to acquire the new printer for Tsuburaya Productions because it was one of the adaptable postproduction tools and he had used Oxberry's previous iteration of the device on films such as Matango. He operated this technology on Ultra Q, Tsuburaya Productions' first television series, which was a combination of his projects that he devised that spring, tentatively titled Unbalance and WoO. Principal photography on Ultra Q began on September 27, 1964, with the shooting of the episode "Mammoth Flower". Broadcast on the Tokyo Broadcasting System from January 2 to July 3, 1966, the series centers on a trio who investigates strange phenomena ranging from supernatural threats to kaiju in the 20th century. Upon broadcast, 30% of Japanese households with televisions watched the show, making Eiji Tsuburaya a household name and gaining him even more attention from the media who dubbed him the "God of Tokusatsu".

After directing the effects on Honda's kaiju film Dogora (released in August 1964), he worked on another Honda-directed kaiju film, Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster, making 1964 the only time two Godzilla pictures were released in the same year. As it was produced as one of the features celebrating ten years of Toho's kaiju films, it featured a dragon kaiju designed as an homage to Yamata no Orochi, King Ghidorah, who opposed Godzilla, Rodan, and Mothra in the film. Screenwriter Shinichi Sekizawa proposed to Tsuburaya that the Ghidorah suit be constructed from light silicon-based textiles to allow more mobility for the suit actor. Tsuburaya and Toho executives decided to anthropomorphize the monsters, despite Honda feeling "uncomfortable" with the decision and being reluctant to use The Peanuts (who previously played the Mothra's fairies in the namesake film) as the interpreters for the kaiju in the summit scene. During the shooting of Godzilla and Rodan's match in Toho Studios' enormous water tank, one of the borders of the tank was exposed on film. Tsuburaya hid this mistake by superimposing trees in the area. Released on December 20, 1964, Ghidorah was a massive box office hit, grossing ¥375 million (equivalent to over $1 million in 2017), relatively more than King Kong vs. Godzilla, the series' previous record holder. King Ghidorah would go on to become a frequent antagonist of the Godzilla franchise.

Tsuburaya's next production originated in the United States around 1960 when King Kong stop-motion animator Willis H. O'Brien proposed King Kong vs. Frankenstein. O'Brien hired John Beck to produce this project and then offered the idea to Toho, who scrapped the concept in favor of Kong battling Godzilla, and thus became the blockbuster King Kong vs. Godzilla in 1962. The following year, Sekizawa took O'Brien's concept and wrote the screenplay Frankenstein vs. The Human Vapor, a planned entry in the Transforming Human Series. However, the project was canceled after Matango became a box office failure upon its release that year. In July 1964, screenwriter Kaoru Mabuchi submitted a screenplay titled Frankenstein vs. Godzilla, however, it was abandoned in favor of Mothra vs. Godzilla. Therefore, Mabuchi converted his Frankenstein vs. Godzilla screenplay into a new script that had Frankenstein's monster fight a new subterranean kaiju named Baragon. Tsuburaya was enthusiastic about this picture, entitled Frankenstein vs. Baragon, because the titular monsters were going to be more diminutive than normal, allowing his team to build larger model sets than their Godzilla movies, and an actor in makeup—Kōji Furuhata—would play Frankenstein rather than a stuntman in a monster suit. In spite of featuring model sets among the most enormous and intricate detailed models for a Honda-Tsuburaya collaboration, some critics have questioned why Tsuburaya used a puppet to portray a horse for a sequence in which Baragon overruns a farmstead instead of another method such as a shot of an actual equine. According to Koichi Takano, Tsuburaya said that he used the puppet because it was "more fun". Tsuburaya also made a scene depicting the Atomic bomb falling upon Hiroshima, which Honda biographers Steve Ryfle and Ed Godziszewski called an "impressionistic display of smoke and fire".

After postproduction on the film was finalized for its Japanese release two days after the twentieth anniversary of the Hiroshima atomic bombing (August 8, 1965), American co-producer Henry G. Saperstein asked for Toho to film a new ending for the U.S. version where Frankenstein confronts a giant octopus that drowns him in a lake at Mount Fuji rather than Frankenstein, after defeating Baragon, falling into an aperture that opens underneath him at the bottom of the mountain. Tsuburaya and Honda, accordingly, reassembled the cast and crew to shoot the new ending which was eventually left unused in both American and Japanese iterations of the motion picture, though it later was screened at a fan convention in 1982 and featured as a bonus on home video.

After directing the effects for Seiji Maruyama's war film Retreat From Kiska (released in June 1965), Tsuburaya began work on Honda's Invasion of Astro-Monster (1965), the sixth film in the Godzilla franchise and Shōwa period as well as the second collaboration between Toho and UPA. A direct sequel to Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster, it focuses on two astronauts who land on a planet occupied by an alien race known as the Xiliens who ask humanity for assistance with Godzilla and Rodan in defeating King Ghidorah, who they claim is intruding on their homeworld. After bringing the astronauts, scientist Sakurai, Godzilla, and Rodan to their planet the aliens attempt to use Ghidorah, Godzilla, and Rodan to conquer the Earth via mind-controlling them. The last Godzilla film to feature the contributions of Tsuburaya's entire effects unit, it notably features Godzilla's renowned Shie victory dance that was included in the film after actor Yoshio Tsuchiya suggested it to Tsuburaya, who was already supportive of anthropomorphizing monster characters with comical characteristics. For his work on Kiska, he won a Japan Technical Award for Special Skill at the 19th Japan Technical Awards and obtained another for Invasion of Astro-Monster the following year.

Ultraman and beyond (1966–1967)

In 1966, his company aired the first Ultra series for television, Ultra Q beginning in January, followed by the highly popular Ultraman in July, and premiered a comedy-monster series, Monster Booska in November. Ultraman became the first live-action Japanese television series to be exported worldwide, spawning the Ultra series which continues to this day.

Final works and last years (1968–1970)

Toward the end of his life, Tsuburaya dedicated himself to planning for a film titled Japan Airplane Guy. Despite preliminary work, it was never filmed. Tsuburaya was advised to reduce his workload due to declining health. Still, he continued to take on more and more projects, dividing his time between Tsuburaya Productions and directing special effects for two Toho films, Latitude Zero and Battle of the Japan Sea. In addition, Mitsubishi hired him to oversee a special exhibit at Expo '70, the World's Fair in Osaka. On January 25, 1970, at 10:15 P.M., he died of a heart attack caused by bronchial asthma, while sleeping with his wife in their home in Itō, Shizuoka. Five days after he died, on January 30, 1970, Emperor Hirohito awarded him the "Order of the Sacred Treasure." His funeral was held at Toho Studios on February 2, with Sanezumi Fujimoto providing the services. He was later entombed at Catholic Cemetery in Fuchū, Tokyo, Japan.

Filmmaking

Filming and editing

According to special effects cinematographer Sadamasa Arikawa, Tsuburaya also edited his own film work. Tsuburaya's assistant director, Masakatsu Asai, stated that memorized the situation and storage location of the cuts he shot. Scripter Keiko Suzuki said Tsuburaya envisioned his own editing plan, and he often filmed scenes unscripted. Thus, for instance, scenes were altered to become "Battle 1" and "Aerial Battle 2".

Legacy

Tsuburaya Productions described Tsuburaya as the "Father of Tokusatsu" because of his "astounding balancing act of technique and entertainment". The Independent's Doug Bolton wrote that even "people not familiar with Japanese science fiction will easily recognise [sic] the legacy of Tsuburaya's work". The Tokusatsu Network said that Tsuburaya was "possibly the most influential figure in the Japanese film industry" and stated that his legacy "lives on to this day through his creations and has had a large enough impact for him to be compared to Walt Disney."

Posthumous works

Tsuburaya had intended to work on Space Amoeba (1970), but he died shortly after filming began. While the film was completed in Tsuburaya's honor and was his last project to be involved in, Toho executives refused to grant him a dedication in its opening credits.

A number of posthumous works have been created based on or inspired by Tsuburaya's unfilmed concepts. A script for a project entitled Princess Kaguya was written by Tsuburaya shortly before he died in Izu. Motivated by his father's desire to work on another adaptation of the tale, Hajime Tsubruaya attempted to produce Princess Kaguya into a film for Tsuburaya Productions' 10th anniversary. In the preface of Hiroyasu Yamaura's script for the film, Tsuburaya said he had taken "great pains to incorporate the strengths of various folk tales and fairy tales into a work that children around the world would honestly enjoy". Despite his tireless efforts, he passed away on the morning of February 9, 1973, before director Yoshiyuki Kuroda was scheduled to begin production that evening. Thus, production on the project was canceled. In 1987, producer Tomoyuki Tanaka turned Eiji Tsuburaya's lifelong ambition into a live-action movie titled Princess from the Moon, which featured effects directed by Tsuburaya's protégé Teruyoshi Nakano.

In 2020, filmmaker Minoru Kawasaki created a film loosely based on his unmade film prior to production of Godzilla, featuring a giant octopus.

Portrayals

Many actors have played Tsuburaya in television dramas and programs. For his portrayal in the 1989 television drama The Men Who Made Ultraman, an unidentified renowned Toho actor who had been starring in many of the company's box office hits since before Godzilla (1954) was initially cast as Tsuburaya. However, the famed actor declined the offer, believing he lacked similarities in appearance to Tsuburaya. Therefore, actor Kō Nishimura was cast instead. In 1993, filmmaker Seijun Suzuki played Tsuburaya in the television drama I Loved Ultraseven. For The Pair of Ultraman, a 2022 television documentary on the two screenwriters behind Ultraman, he was portrayed by Toshiki Ayada.

Tributes

In honor of the 114th anniversary of his birth, Google made an animated doodle of his skill with special effects on July 7, 2015. On January 11, 2019, the Eiji Tsuburaya Museum opened in his hometown of Sukagawa, a tribute to his life and work in film and television.

Selected filmography

Films

- A Page of Madness (1926)

- Princess Kaguya (1935)

- The New Land (1937)

- The Abe Clan (1938)

- The Burning Sky (1940)

- The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya (1942)

- General Kato's Falcon Fighters (1944)

- A Thousand and One Nights with Toho (1947)

- Lady from Hell (1949)

- The Invisible Man Appears (1949)

- Escape at Dawn (1950)

- The Skin of the South (1952)

- The Man Who Came to Port (1952)

- Anatahan (1953)

- Eagle of the Pacific (1953)

- Farewell Rabaul (1954)

- Godzilla (1954)

- The Invisible Avenger (1954)

- Godzilla Raids Again (1955)

- Half Human (1955)

- The Legend of the White Serpent (1956)

- Rodan (1956)

- Throne of Blood (1957)

- The Mysterians (1957)

- The H-Man (1958)

- Varan (1958)

- The Hidden Fortress (1958)

- Monkey Sun (1959)

- Submarine I-57 Will Not Surrender (1959)

- The Three Treasures (1959)

- Battle in Outer Space (1959)

- The Secret of the Telegian (1960)

- Storm Over the Pacific (1960)

- The Human Vapor (1960)

- The Story of Osaka Castle (1961)

- Mothra (1961)

- The Last War (1961)

- Gorath (1962)

- King Kong vs. Godzilla (1962)

- Chūshingura: Hana no Maki, Yuki no Maki (1962)

- Attack Squadron! (1963)

- Matango (1963)

- The Lost World of Sinbad (1963)

- Atragon (1963)

- Whirlwind (1964)

- Mothra vs. Godzilla (1964)

- Dogora (1964)

- Ghidorah, the Three-Headed Monster (1964)

- None but the Brave (1965)

- Frankenstein vs. Baragon (1965)

- Invasion of Astro-Monster (1965)

- The War of the Gargantuas (1966)

- Ebirah, Horror of the Deep (1966)

- King Kong Escapes (1967)

- Son of Godzilla (1967)

- Destroy All Monsters (1968)

- Latitude Zero (1969)

- Battle of the Japan Sea (1969)

- All Monsters Attack (1969)

Television

- Ultra Q (1966)

- Modern Leaders [episode, "The Father of Ultra Q"] (1966)

- Ultraman (1966-1967)

- Monster Booska (1966-1967)

- Mighty Jack (1968)

- Fight! Mighty Jack (1968)

Awards and honors

| Year | Award | Category | Nominated work | Result | Ref(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1940 | Japan Motion Picture Cinematographers Association | Special Technology Award | The Burning Sky | Won | |

| 1942 | Technical Research Award | The War at Sea from Hawaii to Malaya |

|||

| 1954 | 8th Japan Technical Awards | Special Skill | Godzilla | ||

| 1957 | 11th Japan Technical Awards | The Mysterians | |||

| 1959 | 13th Japan Technical Awards | The Three Treasures | |||

| 4th Movie Day | Special Award of Merit | N/A | |||

| 1963 | 17th Japan Technical Awards | Special Skill | The Lost World of Sinbad | ||

| 1965 | 19th Japan Technical Awards | Retreat From Kiska | |||

| 1966 | 20th Japan Technical Awards | Invasion of Astro-Monster | |||

| 1970 | N/A | 4th Class Medal of Order of the Sacred Treasure |

N/A | ||

| Japanese Society of Cinematographers | Honorary Chairman Award |

See also

In Spanish: Eiji Tsuburaya para niños

In Spanish: Eiji Tsuburaya para niños