Elizabeth Siddal facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Elizabeth Siddal

|

|

|---|---|

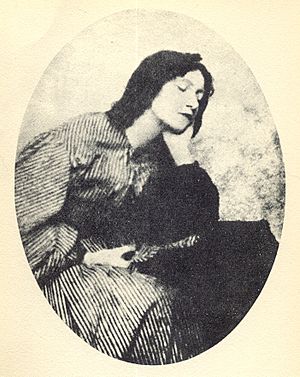

Siddal, c. 1860

|

|

| Born |

Elizabeth Eleanor Siddall

25 July 1829 London, England

|

| Died | 11 February 1862 (aged 32) Blackfriars, London, England

|

| Occupation |

|

| Spouse(s) | |

Elizabeth Eleanor Siddall (25 July 1829 – 11 February 1862), better known as Elizabeth Siddal, was an English artist, poet, and artists' model. Significant collections of her artworks can be found at Wightwick Manor and the Ashmolean. Siddal was painted and drawn extensively by artists of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, including Walter Deverell, William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais (including his notable 1852 painting Ophelia), and especially by her husband, Dante Gabriel Rossetti.

Early life

Elizabeth Eleanor Siddall, named after her mother, was born on 25 July 1829, at the family's home at 7 Charles Street, Hatton Garden. Her parents were Charles Crooke Siddall, and Elizabeth Eleanor Evans, from a family of English and Welsh descent. She had two older siblings, Ann and Charles Robert. At the time of her birth, her father had a cutlery-making business.

About 1831, the Siddalls moved to the less affluent borough of Southwark, in south London. The rest of Siddal's siblings were born in Southwark; Lydia, to whom she was particularly close; Mary, Clara, James and Henry. Siddal "received an ordinary education, conformable to her condition in life" and first "read Tennyson by finding one or two poems of his on a piece of paper" that had been wrapped around some butter. This engendered a love of poetry while young and inspired her to write her own.

Pre-Raphaelite Model

In 1849, while working at a millinery in Cranbourne Alley, London, Siddal made the acquaintance of Walter Deverell. Accounts differ on the circumstances of their meeting: in one account, William Allingham noticed her when he came to admire a co-worker, and then recommended her as a possible model to his friend Deverell, who was struggling with a large oil painting based on the Shakespeare play Twelfth Night. Another account has Deverell accompanying his mother to the millinery where he noticed Siddal in the back of the shop. In either case, Deverell later described Siddal as "magnificently tall, with a lovely figure, and a face of the most delicate and finished modelling ... she has grey eyes, and her hair is like dazzling copper, and shimmers with luster." Deverell subsequently employed Siddal as a model and introduced her to the Pre-Raphaelites.

As with the other Pre-Raphaelites, Deverell took his inspiration directly from life rather than from an idealized classical figure. In his Twelfth Night painting, he based Orsino on himself, Feste on his friend Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Viola/Cesario on Siddal. This was the first time Siddal sat as a model. According to William Michael Rossetti, Dante Gabriel's brother, "Deverell drew another Viola from her, in an etching for The Germ." Elaine Shefer asserts that Deverell portrayed Siddal in A Pet and The Grey Parrot.

William Holman Hunt painted her in A Converted British Family Sheltering a Christian Missionary from the Persecution of the Druids (1849–1850) and Two Gentlemen of Verona, Valentine Rescuing Sylvia From Proteus (1850 or 1851).

For Millais's Ophelia, Siddal floated in a bathtub full of water to portray Ophelia. Millais painted daily through the winter, putting oil lamps under the tub to warm the water. On one occasion, the lamps went out and the water became icy cold. Millais, absorbed by his painting, did not notice and Siddal did not complain. After this, she became ill with a severe cold or pneumonia. Her father held Millais responsible and, under the threat of legal action, Millais paid her doctor's bills.

Relationship with Rossetti

Dante Gabriel Rossetti met Siddal in 1849, probably while they both modelled for Deverell. Rossetti gave Siddal the nickname "Lizzie" when she entered the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood circle, and "the diminutive enhanced her youthful, dependent role." By 1851, she had become Rossetti's muse, and he began to paint her to the exclusion of nearly all others. He also stopped Siddal from modelling for others.

In 1852, she began to study with Rossetti. That same year, Siddal became lovers with Rossetti and moved into his Chatham Place residence. They subsequently became anti-social and absorbed in each other's affections. They coined affectionate nicknames for one another, such as "Guggums" or "Gug" and "Dove", the latter one of Rossetti's names for Siddal. He also shortened the spelling of her name to Siddal, dropping the second 'l'.

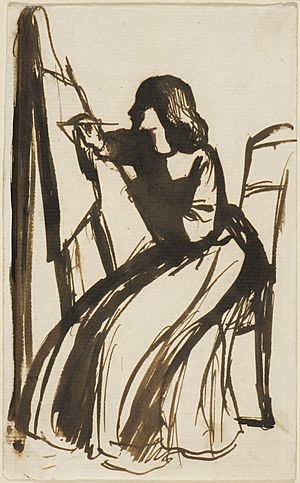

Perhaps Rossetti's most abundant and personal works were his idealized pencil sketches of Siddal at home, most of which he entitled simply "Elizabeth Siddal". In these sketches, he portrayed Siddal as a woman of leisure, class, and beauty, often situated in comfortable settings. She also became the subject of much of Rossetti's poetry. One poem, A Last Confession, extolls his love for Siddal, whom he personifies as the heroine with eyes "as of the sea and sky on a grey day."

Beginning in 1853, Rossetti used Siddal as a model for a series of Dante-themed paintings, including The First Anniversary of the Death of Beatrice (1852), Beatrice Meeting Dante at a Marriage Feast, Denies him her Salutation (1851), Dante's Vision of Rachel and Leah (1855), and, perhaps his most famous portrait of her, Beata Beatrix (1864–1870), which he painted as a memorial after her death.

It has been estimated that there are thousands of Rossetti's drawings, paintings, and poems in which Siddal was a subject.

Work

In 1854, Siddal painted a self-portrait that differed from the typical Pre-Raphaelite idealised beauty. In 1855, art critic John Ruskin began to subsidise her career and paid £150 per year in exchange for all the drawings and paintings she produced. She produced many sketches, drawings, and watercolours as well as one oil painting. Her sketches are similar to other Pre-Raphaelite compositions illustrating Arthurian legend and other idealized medieval themes, and she exhibited with the Pre-Raphaelites at the summer exhibition at Russell Place in 1857.

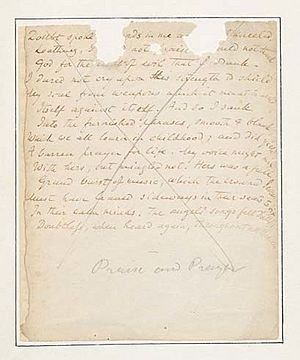

During Siddal’s career as an artist and poet from 1852 to 1861, she produced over 100 works. Siddal also wrote poetry during this period, often with dark themes about lost love or the impossibility of true love. "Her verses were as simple and moving as ancient ballads; her drawings were as genuine in their medieval spirit as much more highly finished and competent works of Pre-Raphaelite art," wrote critic William Gaunt. Both Rossetti and Ford Madox Brown supported and admired her work.

Relationship with Rossetti's family and marriage

As Siddal came from a working-class family, Rossetti feared introducing her to his parents. Siddal was the victim of harsh criticism from his sisters. The knowledge that his family would not approve contributed to Rossetti delaying the marriage. Siddal appears to have believed, with some justification, that Rossetti was always seeking to replace her with a younger muse, which contributed to her later depressive periods and illness.

Shortly before their marriage, Rossetti produced a famous portrait of Siddal, Regina Cordium or The Queen of Hearts (1860). This painting is a close-up, vibrantly coloured depiction of Siddal.

Siddal and Rossetti married on Wednesday, 23 May 1860 at St. Clement's Church in the seaside town of Hastings. There were no family or friends present, only a couple of witnesses whom they had asked in Hastings.

Ill health and death

It was thought that Siddal suffered from tuberculosis, but some historians believe an intestinal disorder was more likely. Elbert Hubbard wrote that "She suffered much from neuralgia, and the laudanum taken to relieve the pain had grown into a necessity." Others have suggested she might have been anorexic while others attribute her poor health to a combination of ailments.

Siddal travelled to Paris and Nice for several years for her health. At the time of her wedding, she was so frail and ill that she had to be carried to the church, despite it being a five-minute walk from where she was staying. In 1861, Siddal became pregnant, which ended with the birth of a stillborn daughter.

Siddal died on 11 February 1862 at their home at 14 Chatham Place. The coroner ruled her death as accidental.

After Siddal's death

Siddal was buried with her father-in-law Gabriele on 17 February 1862 in the Rossetti family grave in the west side of Highgate Cemetery. Later burials in the same grave are her mother-in-law Frances Rossetti (1886), Christina Georgina Rossetti (1895), and William Michael Rossetti (1919).

In August 1869, Rossetti authorized Charles Howell to disinter her coffin to retrieve a handwritten book of Rossetti's poems, which he had laid beside her head before burial. With the aid of a Dr. Llewelyn Williams and two others, Howell accomplished this in October 1869. Dr. Williams subsequently disinfected the book. Rossetti then published the contents in Poems (1870).

Legacy

Their home at 14 Chatham Place was demolished and is now covered by Blackfriars Station.

Exhibitions and collections

The first solo exhibition of Siddal's work was curated by Jan Marsh in 1991 at the Ruskin Gallery in Sheffield.

Rosalie Glynn Grylls and Geoffrey Mander paid a record sum for her work in the 1960s and donated the art to the National Trust. A 2018 exhibition, "Beyond Ophelia", curated by National Trust Assistant Curator Hannah Squire, ran at Wightwick Manor for nine months and featured twelve artworks by Siddal and owned by the National Trust. Only the second solo exhibition of her work, the exhibition examined Siddal's career, artistic style, subject matter, and the prejudice she faced as a female artist, whilst also exploring the Manders of Wightwick as pioneering collectors.

The oil painting Self Portrait (1853–54) and watercolour Lady Clare (1857) are currently in private collections.

Lady Affixing a Pennant to a Knight’s Spear (1856), Sir Patrick Spens (1856), and The Quest of the Holy Grail(1855) have all been exhibited in the Tate Gallery in London.

The finished drawings The Lady of Shalott and Pippa Passes (1854) are respectively displayed in the J.S. Maas Collection and the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford.

Siddal’s paintings also include Clerk Saunders (1857), The Haunted Wood, and Madonna and Child with an Angel (c. 1856).

Gallery

Works by Siddal

Works with Siddal as a model

-

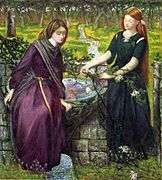

William Holman Hunt, Two Gentlemen of Verona, Valentine Rescuing Sylvia From Proteus, 1850 or 1851

See also

In Spanish: Elizabeth Siddal para niños

In Spanish: Elizabeth Siddal para niños