Fable facts for kids

A fable is a type of story which shows something in life or has a meaning to a word. A fable is a funny story but may teach a lesson or suggest a moral from it. A fable starts in the middle of the story, that means, jumps into the main event without detailed introduction of characters. The characters of a fable may be people, animals, gods, or anything else. When animals and objects are used in fables, they think and talk like people, even though they act like animals or objects. For example, in a fable a clay pot might say that it is frightened of being broken.

The stories told by fables are usually very simple. To understand a fable, the reader or listener does not need to know all about the characters, only one important thing. For this reason animals are often used in fables in a way that is easily understood because it is always the same. They keep the same characteristics from story to story.

- A lion is noble

- A rooster is boastful

- A peacock is proud

- A fox is cunning

- A wolf is fierce

- A horse is brave

- A donkey is hard-working

The most famous fables are those attributed to Aesop (6th century B.C.). Many fables are so well-known that their morals have become English sayings.

For example:

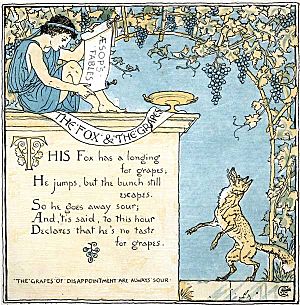

- If a person says "sour grapes!" then they are referring to "The Fox and the Grapes". This fable is about a fox who saw a beautiful bunch of grapes hanging on a vine. He wanted to eat them but they were high up. He tried and tried to jump high enough to pull them down. When he was too tired to jump anymore, he went away saying "I'll bet those grapes were sour!"

- So, if a person sees a beautiful thing that they want, but cannot have, sometimes they say "I don't want it, anyway! I'll bet it is really no good!" This way of thinking is called "sour grapes".

- "Crying wolf" is another well-known English saying. This comes from "The Boy Who Cried Wolf". This fable is about a boy who was sent to mind the sheep. The owners of the sheep said, "If a wolf comes to eat the sheep, you must shout loudly, and we will chase the wolf away!" But the boy got lonely while minding the sheep. So after a while he shouted "Wolf! Wolf!" The people came running. When they saw there was no wolf, they were angry. The next day the boy got lonely again, so he shouted "Wolf! Wolf!" The people came running, but there was no wolf. They were very angry with the boy! On the third day the boy saw a large grey animal hiding behind the rocks and watching the sheep. He cried "Wolf! Wolf!" as loudly as he could, but no one came to chase the wolf away, and at the end of the day, when the people came to look for him, there was nothing left but his bones.

- So if a person always makes a great fuss to get attention, or if a person says something bad has happened when it has not, then it is called "crying wolf" and people will stop bothering to pay attention, even when things go really wrong.

Contents

History

The fable is one of the most enduring forms of folk literature, spread abroad, modern researchers agree, less by literary anthologies than by oral transmission. Fables can be found in the literature of almost every country.

Aesopic or Aesop's fable

The varying corpus denoted Aesopica or Aesop's Fables includes most of the best-known western fables, which are attributed to the legendary Aesop, supposed to have been a slave in ancient Greece around 550 BC. When Babrius set down fables from the Aesopica in verse for a Hellenistic Prince "Alexander," he expressly stated at the head of Book II that this type of "myth" that Aesop had introduced to the "sons of the Hellenes" had been an invention of "Syrians" from the time of "Ninos" (personifying Nineveh to Greeks) and Belos ("ruler"). Epicharmus of Kos and Phormis are reported as having been among the first to invent comic fables. Many familiar fables of Aesop include "The Crow and the Pitcher", "The Tortoise and the Hare" and "The Lion and the Mouse". In ancient Greek and Roman education, the fable was the first of the progymnasmata—training exercises in prose composition and public speaking—wherein students would be asked to learn fables, expand upon them, invent their own, and finally use them as persuasive examples in longer forensic or deliberative speeches. The need of instructors to teach, and students to learn, a wide range of fables as material for their declamations resulted in their being gathered together in collections, like those of Aesop.

Africa

African oral culture has a rich story-telling tradition. As they have for thousands of years, people of all ages in Africa continue to interact with nature, including plants, animals and earthly structures such as rivers, plains and mountains. Grandparents enjoy enormous respect in African societies and fill the new role of story-telling during retirement years. Children and, to some extent, adults are mesmerized by good story-tellers when they become animated in their quest to tell a good fable.

Joel Chandler Harris wrote African-American fables in the Southern context of slavery under the name of Uncle Remus. His stories of the animal characters Brer Rabbit, Brer Fox, and Brer Bear are modern examples of African-American story-telling that transcends critiques and controversies as to whether or not Uncle Remus was a racist or apologist for slavery. The Disney movie Song of the South introduced many of the stories to the public and others not familiar with the role that story-telling played in the life of cultures and groups without training in speaking, reading, writing, or the cultures to which they had been relocated to from world practices of capturing Africans and other indigenous populations to provide slave labor to colonized countries.

India

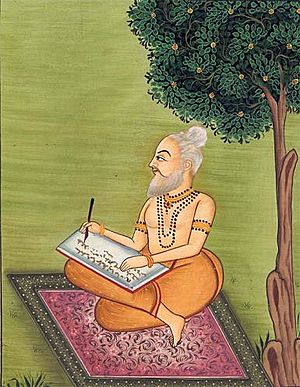

India has a rich tradition of fabulous novels, mostly explainable by the fact that the culture derives traditions and learns qualities from natural elements. Most of the gods are some form of animals with ideal qualities. Also hundreds of fables were composed in ancient India during the first millennium BC, often as stories within frame stories. Indian fables have a mixed cast of humans and animals. The dialogues are often longer than in fables of Aesop and often witty as the animals try to outwit one another by trickery and deceit. In Indian fables, man is not superior to the animals. The tales are often comical. The Indian fable adhered to the universally known traditions of the fable. The best examples of the fable in India are the Panchatantra and the Jataka tales. These included Vishnu Sarma's Panchatantra, the Hitopadesha, Vikram and The Vampire, and Syntipas' Seven Wise Masters, which were collections of fables that were later influential throughout the Old World. Ben E. Perry (compiler of the "Perry Index" of Aesop's fables) has argued controversially that some of the Buddhist Jataka tales and some of the fables in the Panchatantra may have been influenced by similar Greek and Near Eastern ones. Earlier Indian epics such as Vyasa's Mahabharata and Valmiki's Ramayana also contained fables within the main story, often as side stories or back-story. The most famous folk stories from the Near East were the One Thousand and One Nights, also known as the Arabian Nights.

Europe

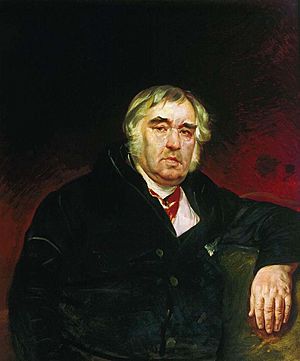

Fables had a further long tradition through the Middle Ages, and became part of European high literature. During the 17th century, the French fabulist Jean de La Fontaine (1621–1695) saw the soul of the fable in the moral — a rule of behavior. Starting with the Aesopian pattern, La Fontaine set out to satirize the court, the church, the rising bourgeoisie, indeed the entire human scene of his time. La Fontaine's model was subsequently emulated by England's John Gay (1685–1732); Poland's Ignacy Krasicki (1735–1801); Italy's Lorenzo Pignotti (1739–1812) and Giovanni Gherardo de Rossi (1754–1827); Serbia's Dositej Obradović (1739–1811); Spain's Félix María de Samaniego (1745–1801) and Tomás de Iriarte y Oropesa (1750–1791); France's Jean-Pierre Claris de Florian (1755–94); and Russia's Ivan Krylov (1769–1844).

Modern era

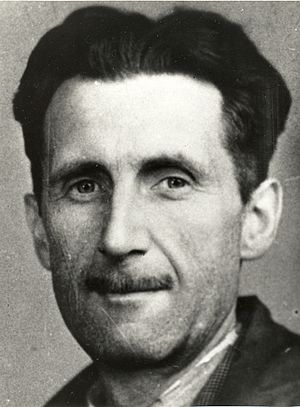

In modern times, while the fable has been trivialized in children's books, it has also been fully adapted to modern adult literature. Felix Salten's Bambi (1923) is a Bildungsroman — a story of a protagonist's coming-of-age — cast in the form of a fable. James Thurber used the ancient fable style in his books Fables for Our Time (1940) and Further Fables for Our Time (1956), and in his stories "The Princess and the Tin Box" in The Beast in Me and Other Animals (1948) and "The Last Clock: A Fable for the Time, Such As It Is, of Man" in Lanterns and Lances (1961). Władysław Reymont's The Revolt (1922), a metaphor for the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, described a revolt by animals that take over their farm in order to introduce "equality." George Orwell's Animal Farm (1945) similarly satirized Stalinist Communism in particular, and totalitarianism in general, in the guise of animal fable.

In the 21st century the Neapolitan writer Sabatino Scia is the author of more than two hundred fables that he describes as “western protest fables.” The characters are not only animals, but also things, beings and elements from nature. Scia’s aim is the same as in the traditional fable, playing the role of revealer of human society. In Latin America, the brothers Juan and Victor Ataucuri Garcia have contributed to the resurgence of the fable. But they do so with a novel idea: use the fable as a means of dissemination of traditional literature of that place.

Fable Writers

Other pages

Images for kids

-

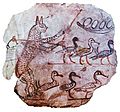

Anthropomorphic cat guarding geese, Egypt, ca. 1120 BCE

See also

In Spanish: Fábula para niños

In Spanish: Fábula para niños