François Rabelais facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

François Rabelais

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | between 1483 and 1494 Chinon, Touraine, France |

| Died | prior to 14 March 1553 (aged between 61 and 70) Paris, France |

| Occupation | Writer, physician, humanist, clergyman |

| Alma mater |

|

| Literary movement | Renaissance humanism |

| Notable works | Gargantua and Pantagruel |

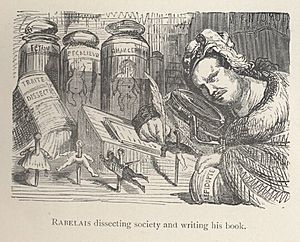

François Rabelais (UK: /ˈræbəleɪ/ rab-Ə-lay, US: /ˌræbəˈleɪ/ --lay, French: [fʁɑ̃swa ʁablɛ]; born between 1483 and 1494; died 1553) was a French Renaissance writer, physician, Renaissance humanist, monk and Greek scholar. He is primarily known as a writer of satire, of the grotesque, and of bawdy jokes and songs.

Both Ecclesiastical and anticlerical, Christian and a free thinker, a doctor and a bon vivant, the multiple facets of his personality sometimes seem contradictory. Caught up in the religious and political turmoil of the Reformation, Rabelais treated the great questions of his time in his novels. Assessments of his life and work have evolved over time depending on dominant paradigms of thought.

Rabelais admired Erasmus and is considered a Christian humanist. He was critical of medieval scholasticism, the abuses of powerful princes and popes, opposing them with Greco-Roman learning and popular culture. His taste for popular satire led John Calvin to attack Rabelais in 1550.

Known most widely for the first two volumes relating the childhoods of the giants Gargantua and Pantagruel in the style of bildungsroman, Rabelais' later work in the Third Book and the Fourth Book prefigures the philosophical novel and the parodic epic.

His literary legacy is such that the word Rabelaisian designates something that is "marked by gross robust humor, extravagance of caricature, or bold naturalism".

Contents

Biography

The place and date of his birth are unknown. He was probably born in November 1494 near Chinon in the province of Touraine, where his father worked as a lawyer. The estate of La Devinière in Seuilly in the modern-day Indre-et-Loire, allegedly the writer's birthplace, houses a Rabelais museum.

Rabelais became a novice of the Franciscan Order, and was later sent to Fontenay-le-Comte in Poitou, where he studied Greek and Latin as well as science, philology, and law, already becoming known and respected by the humanists of his era, including Guillaume Budé (1467–1540). Frustrated with the Franciscan order's ban on the study of Greek (because of Erasmus' commentary on the Greek version of the Gospel of Saint Luke), Rabelais petitioned Pope Clement VII (1523–1534) and gained permission to leave the Franciscans and to enter the Benedictine Order at Maillezais in Poitou.

Later he left the monastery to study medicine at the University of Poitiers and at the University of Montpellier. In 1532 he moved to Lyon, one of the intellectual centres of the Renaissance, and began working as a doctor at the hospital Hôtel-Dieu de Lyon. During his time in Lyon, he edited Latin works for the printer Sebastian Gryphius, and wrote a famous admiring letter to Erasmus to accompany the transmission of a Greek manuscript from the printer. Gryphius published Rabelais' translations & annotations of Hippocrates, Galen and Giovanni Manardo. As a physician, he used his spare time to write and publish humorous pamphlets critical of established authority and preoccupied with the educational and monastic mores of the time.

In 1532, under the pseudonym Alcofribas Nasier (an anagram of François Rabelais), he published his first book, Pantagruel King of the Dipsodes, the first of his Gargantua series. The idea of basing an allegory on the lives of giants came to Rabelais from the folklore legend of les Grandes chroniques du grand et énorme géant Gargantua, which were sold as popular literature at the time in the form of inexpensive pamphlets by colporteurs and at the fairs of Lyon. Pantagruelisme is an "eat, drink and be merry" philosophy, which led his books into disfavor with the theologians but brought them popular success and the admiration of later critics for their focus on the body. This first book, critical of the existing monastic and educational system, contains the first known occurrence in French of the words encyclopédie, caballe, progrès, and utopie, among others. Despite the book's popularity, both it and the subsequent prequel book (1534) about the life and exploits of Pantagruel's father Gargantua were condemned by the Sorbonne in 1543 and other clerics in 1545. Rabelais taught medicine at Montpellier in 1534 and again in 1539. In 1537, Rabelais gave an anatomy lesson at Lyon's Hôtel-Dieu using the corpse of a hanged man; Etienne Dolet, with whom Rabelais was close at this time, wrote of these anatomy lessons in his Carmina.

Rabelais traveled frequently to Rome with his friend and patient Cardinal Jean du Bellay, and lived for a short time in Turin (1540–?) as part of the household of du Bellay's brother, Guillaume. Rabelais also spent some time lying low, under periodic threat of being condemned of heresy depending upon the health of his various protectors. Only the protection of du Bellay saved Rabelais after the condemnation of his novel by the Sorbonne. In June 1543 Rabelais became a Master of Requests.

Between 1545 and 1547 François Rabelais lived in Metz, then a free imperial city and a republic, to escape the condemnation by the University of Paris. In 1547, he became curate of Saint-Christophe-du-Jambet in Maine and of Meudon near Paris.

With support from members of the prominent du Bellay family, Rabelais had received approval from King Francis I to continue to publish his collection. However, after the king's death in 1547, the academic élite frowned upon Rabelais, and the French Parlement suspended the sale of his fourth book, published in 1552.

Rabelais resigned from the curacy in January 1553 and died in Paris later that year.

Novels

Gargantua and Pantagruel

Gargantua and Pantagruel relates the adventures of Gargantua and his son Pantagruel. The tales are adventurous and erudite, festive and gross, and rarely—if ever—solemn for long. The first book, chronologically, was Pantagruel: King of the Dipsodes and the Gargantua mentioned in the Prologue refers not to Rabelais' own work but to storybooks that were being sold at the Lyon fairs in the early 1530s. In the first chapter of the earliest book, Pantagruel's lineage is listed back 60 generations to a giant named Chalbroth. The narrator dismisses the skeptics of the time—who would have thought a giant far too large for Noah's Ark—stating that Hurtaly (the giant reigning during the flood and a great fan of soup) simply rode the Ark like a kid on a rocking horse.

Although most chapters are humorous, wildly fantastic and frequently absurd, a few relatively serious passages have become famous for expressing humanistic ideals of the time. In particular, the chapters on Gargantua's boyhood and Gargantua's paternal letter to Pantagruel present a quite detailed vision of education.

Thélème

In the second novel, Gargantua, M. Alcofribas narrates the Abbey of Thélème, built by the giant Gargantua. It differs markedly from the monastic norm, since it is open to both monks and nuns and has a swimming pool, maid service, and no clocks in sight. Only the good-looking are permitted to enter. The inscription at the gate first specifies who is not welcome: hypocrites, bigots, the pox-ridden, Goths, Magoths, straw-chewing law clerks, usurious grinches, old or officious judges, and burners of heretics. When the members are defined positively, the text becomes more inviting:

Honour, praise, distraction

Herein lies subtraction

in the tuning up of joy.

To healthy bodies so employed

Do pass on this reaction:

Honour, praise, distraction

The Thélèmites in the abbey live according to a single rule:

DO WHAT YOU WANT

- Fay ce que vouldras

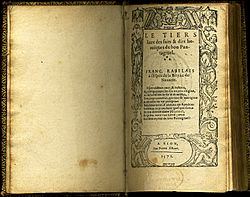

The Third Book

Published in 1546 under his own name with the privilège granted by Francis I for the first edition and by Henri II for the 1552 edition, The Third Book was condemned by the Sorbonne, like the previous tomes. In it, Rabelais revisited discussions he had had while working as a secretary to Geoffroy d'Estissac earlier in Poitiers, where la querelle des femmes had been a lively subject of debate. More recent exchanges with Marguerite de Navarre—possibly about the question of clandestine marriage and the Book of Tobit whose canonical status was being debated at the Council of Trent—led Rabelais to dedicate the book to her before she wrote the Heptameron.

In contrast to the two preceding chronicles, the dialogue between the characters is much more developed than the plot elements in the third book. In particular, the central question of the book, which Panurge and Pantagruel consider from multiple points of view, is an abstract one: whether Panurge should marry or not. Panurge consults authorities vested with revealed knowledge, like the sibyl of Panzoust or the mute Nazdecabre, acquaintances, like the theologian Hippothadée or the philosopher Trouillogan, and even the jester Triboulet. It is likely that several of the characters refer to real people: Abel Lefranc argues that Hippothadée was Jacques Lefèvre d'Étaples, Rondibilis was the doctor Guillaume Rondelet, the esoteric Her Trippa corresponds to Cornelius Agrippa. One of the comic features of the story is the contradictory interpretations Pantagruel and Panurge get embroiled in, the first of which being the paradoxical encomium of debts in chapter III. The Third Book, deeply indebted to In Praise of Folly, contains the first-known attestation of the word paradoxe in French.

The more reflective tone shows the characters' evolution from the earlier tomes. Here Panurge is not as crafty as Pantagruel and is stubborn in his will to turn every sign to his advantage, refusing to listen to advice he had himself sought out. For example, when Her Trippa reads dark omens in his future marriage, Panurge accuses him of the same blind self-love (philautie) from which he seems to suffer. His erudition is more often put to work for pedantry than let to settle into wisdom. By contrast, Pantagruel's speech gains in weightiness by the third book, the exuberance of the young giant having faded.

At the end of the Third Book, the protagonists decide to set sail in search of a discussion with the Oracle of the Divine Bottle. The last chapters are focused on the praise of the Pantagruelion (hemp)—a plant used in the 16th century for both the hangman's rope and medicinal purposes—being copiously loaded onto the ships. As a naturalist inspired by Pliny the Elder and Charles Estienne, the narrator intercedes in the story, first describing the plant in great detail, then waxing lyrical on its various qualities.

The Fourth Book

A first draft edition of The Fourth Book appeared in 1548 containing eleven chapters and many typos. The slipshod nature of this first edition made the circumstances of its publication mysterious, especially for a controversial author. While the prologue denounces slanderers, the story that follows did not raise any polemical issues. Already it contained some of the best-known episodes, including the storm at sea and Panurge's sheep. It was framed as an erratic odyssey, inspired both by the Argonauts and the news of Jacques Cartier's voyage to Canada.

Use of language

The French Renaissance was a time of linguistic contact and debate. The first book of French, rather than Latin, grammar was published in 1530, followed nine years later by the language's first dictionary. Spelling was far less codified. Rabelais, as an educated reader of the day, preferred etymological spelling, preserved clues to the lineage of words, to more phonetic spellings which wash those traces away.

Rabelais' use of Latin, Greek, regional and dialectal terms, creative calquing, gloss, neologism and mis-translation was the fruit of the printing press having been invented less than a hundred years earlier. A doctor by trade, Rabelais was a prolific reader, who wrote a great deal about bodies. His fictional works are filled with multilingual puns, absurd creatures, bawdy songs and lists. Words and metaphors from Rabelais abound in modern French and some words have found their way into English, through Thomas Urquhart's unfinished 1693 translation, completed and considerably augmented by Peter Anthony Motteux by 1708.

Scholarly views

Most scholars today agree that Rabelais wrote from a perspective of Christian humanism. This has not always been the case. Abel Lefranc, in his 1922 introduction to Pantagruel, depicted Rabelais as a militant anti-Christian atheist. On the contrary, M. A. Screech, like Lucien Febvre before him, describes Rabelais as an Erasmian. While formally a Roman Catholic, Rabelais was an adherent of Renaissance humanism, which meant that he favoured classical Antiquity over the "barbarous" Middle Ages and believed in the need of reform to bring science and arts to their classical flourishing and theology and the Church to their original Evangelical form as expressed in the Gospels. In particular, he was critical of monasticism. Rabelais criticised what he considered to be inauthentic Christian positions by both Catholics and Protestants, and was attacked and portrayed as a threat to religion or even an atheist by both. For example, "at the request of Catholic theologians, all four Pantagrueline chronicles were censured by either the Sorbonne, Parliament, or both". On the opposite end of the spectrum, John Calvin saw Rabelais as a representative of the numerous moderate evangelical humanists who, while "critical of contemporary Catholic institutions, doctrines, and conduct", did not go far enough; in addition, Calvin considered Rabelais' apparent mocking tone to be especially dangerous, since it could be easily misinterpreted as a rejection of the sacred truths themselves.

Timothy Hampton writes that "to a degree unequaled by the case of any other writer from the European Renaissance, the reception of Rabelais's work has involved dispute, critical disagreement, and ... scholarly wrangling ..." In particular, as pointed out by Bruno Braunrot, the traditional view of Rabelais as a humanist has been challenged by early post-structuralist analyses denying a single consistent ideological message of his text, and to some extent earlier by Marxist critiques such as Mikhail Bakhtin with his emphasis on the subversive folk roots of Rabelais' humour in medieval "carnival" culture. At present, however, "whatever controversy still surrounds Rabelais studies can be found above all in the application of feminist theories to Rabelais criticism", as he is alternately considered a misogynist or a feminist based on different episodes in his works.

Citing Jean de La Bruyère, the Catholic Encyclopedia of 1911 declared that Rabelais was

... a revolutionary who attacked all the past, Scholasticism, the monks; his religion is scarcely more than that of a spiritually minded pagan. Less bold in political matters, he cared little for liberty; his ideal was a tyrant who loves peace. [...] His vocabulary is rich and picturesque, but licentious and filthy. In short, as La Bruyère says: "His book is a riddle which may be considered inexplicable. Where it is bad, it is beyond the worst; it has the charm of the rabble; where it is good it is excellent and exquisite; it may be the daintiest of dishes." As a whole it exercises a baneful influence.

In literature

In his 1759-1767 novel Tristram Shandy, Laurence Sterne quotes extensively from Rabelais.

Alfred Jarry performed, from memory, hymns of Rabelais at Symbolist Rachilde's Tuesday salons. Jarry worked for years on an unfinished libretto for an opera by Claude Terrasse based on Pantagruel.

Anatole France lectured on him in Argentina. John Cowper Powys, D. B. Wyndham-Lewis, and Lucien Febvre (one of the founders of the French historical school Annales), all wrote books about him.

James Joyce included an allusion to "Master Francois somebody" in his 1922 novel Ulysses.

Mikhail Bakhtin, a Russian philosopher and critic, derived his concepts of the carnivalesque and grotesque body from the world of Rabelais. He points to the historical loss of communal spirit after the Medieval period and speaks of carnival laughter as an "expression of social consciousness".

Aldous Huxley admired Rabelais' work. Writing in 1929, he praised Rabelais, stating "Rabelais loved the bowels which Swift so malignantly hated. His was the true amor fati : he accepted reality in its entirety, accepted with gratitude and delight this amazingly improbable world."

George Orwell was not an admirer of Rabelais. Writing in 1940, he called him "an exceptionally perverse, morbid writer, a case for psychoanalysis".

Milan Kundera, in a 2007 article in The New Yorker, commented on a list of the most notable works of French literature, noting with surprise and indignation that Rabelais was placed behind Charles de Gaulle's war memoirs, and was denied the "aura of a founding figure! Yet in the eyes of nearly every great novelist of our time he is, along with Cervantes, the founder of an entire art, the art of the novel".

Rabelais is treated as a pivotal figure in Kenzaburō Ōe's 1994 acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

In the satirical musical The Music Man by Meredith Willson, the names "Chaucer! Rabelais! Balzac!" are presented by local gossips as evidence that the town librarian "advocates dirty books."

Honours, tributes and legacy

- The public university in Tours, France is named Université François Rabelais.

- Honoré de Balzac was inspired by the works of Rabelais to write Les Cent Contes Drolatiques (The Hundred Humorous Tales). Balzac also pays homage to Rabelais by quoting him in more than twenty novels and the short stories of La Comédie humaine (The Human Comedy). Michel Brix wrote of Balzac that he "is obviously a son or grandson of Rabelais... He has never hidden his admiration for the author of Gargantua that he cites in Le Cousin Pons as "the greatest mind of modern humanity". In his story of Zéro, Conte Fantastique published in La Silhouette on 3 October 1830, Balzac even adopted Rabelais's pseudonym (Alcofribas).

- Rabelais also left a tradition at the University of Montpellier's Faculty of Medicine: no graduating medic can undergo a convocation without taking an oath under Rabelais's robe. Further tributes are paid to him in other traditions of the university, such as its faluche, a distinctive student headcap styled in his honour with four bands of colour emanating from its centre.

- Asteroid '5666 Rabelais' was named in honor of François Rabelais in 1982.

- In Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio's 2008 Nobel Prize lecture, Le Clézio referred to Rabelais as "the greatest writer in the French language".

- In France the moment at a restaurant when the waiter presents the bill is still sometimes called le quart d'heure de Rabelais (The fifteen minutes of Rabelais), in memory of a famous trick Rabelais used to get out of paying a tavern bill.

Works

- Gargantua and Pantagruel, a series of four or five books including:

- Pantagruel (1532)

- La vie très horrifique du grand Gargantua, usually called Gargantua (1534)

- Le Tiers Livre ("The third book", 1546)

- Le Quart Livre ("The fourth book", 1552)

- Le Cinquième Livre (a fifth book, whose authorship is contested)

See also

- Rabelais and His World

- Thomas Urquhart

- Peter Anthony Motteux, (works at wikisource)

- The Great Mare

- Rabelais Student Media