Hjalmar Schacht facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Hjalmar Schacht

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Reichsminister of Economics | |

| In office 3 August 1934 – 26 November 1937 |

|

| President | Adolf Hitler (as Führer) |

| Chancellor | Adolf Hitler |

| Preceded by | Kurt Schmitt |

| Succeeded by | Hermann Göring |

| General Plenipotentiary for War Economy | |

| In office 21 May 1935 – 26 November 1937 |

|

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Walther Funk |

| President of the Reichsbank | |

| In office 12 November 1923 – 7 March 1930 |

|

| Preceded by | Rudolf E. A. Havenstein |

| Succeeded by | Hans Luther |

| In office 17 March 1933 – 20 January 1939 |

|

| Preceded by | Hans Luther |

| Succeeded by | Walther Funk |

| Reichsminister without Portfolio | |

| In office 26 November 1937 – 22 January 1943 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Horace Greeley Hjalmar Schacht

22 January 1877 Tinglev, German Empire |

| Died | 3 June 1970 (aged 93) Munich, West Germany |

| Resting place | Munich Ostfriedhof |

| Political party |

|

| Spouses |

Luise Sowa

(m. 1903; died 1940)Manci Vogler

(m. 1941) |

| Children | Cordula Schacht |

| Profession | Banker, economist |

| Awards | Golden Party Badge |

| Signature |  |

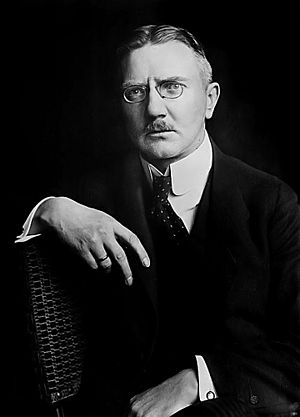

Hjalmar Schacht (born Horace Greeley Hjalmar Schacht; 22 January 1877 – 3 June 1970, German pronunciation: [ˈjalmaʁ ˈʃaxt]) was a German economist, banker, centre-right politician, and co-founder in 1918 of the German Democratic Party. He served as the Currency Commissioner and President of the Reichsbank under the Weimar Republic. He was a fierce critic of his country's post-World War I reparations obligations. He was also central in helping create the group of German industrialists and landowners that forced Hindenburg to form the first NSDAP-government.

He served in Adolf Hitler's government as President of the Central Bank (Reichsbank) 1933–1939 and as Minister of Economics (August 1934 – November 1937).

While Schacht was for a time feted for his role in the German "economic miracle", he opposed elements of Hitler's policy of German re-armament insofar as it violated the Treaty of Versailles and (in his view) disrupted the German economy. His views in this regard led Schacht to clash with Hitler and most notably with Hermann Göring. He resigned as President of the Reichsbank in January 1939. He remained as a Minister-without-portfolio, and received the same salary, until he left the government in January 1943.

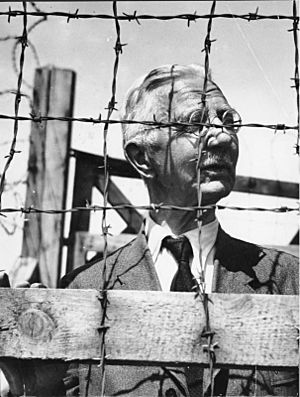

In 1944, Schacht was arrested by the Gestapo following the assassination attempt on Hitler on 20 July 1944 because he allegedly had contact with the assassins. Subsequently, he was interned in the concentration camps and later at Flossenbürg. In the final days of the war, he was one of the 139 special and clan prisoners who were transported by the SS from Dachau to South Tyrol. This location is within the area named by Himmler the "Alpine Fortress", and it is speculated that the purpose of the prisoner transport was with the intent of holding hostages. They were freed in Niederdorf, South Tyrol, in Italy, on 30 April 1945.

Schacht was tried at Nuremberg, but was fully acquitted despite Soviet objections; later on, a German denazification tribunal sentenced him to eight years' hard labor, which was also overturned on appeal.

In 1955, he founded a private banking house in Düsseldorf. He also advised developing countries on economic development.

Contents

Early life and career

Schacht was born in Tingleff, Prussia, German Empire (now in Denmark) to William Leonhard Ludwig Maximillian Schacht and Baroness Constanze Justine Sophie von Eggers, a native of Denmark. His parents, who had spent years in the United States, originally decided on the name Horace Greeley Schacht, in honor of the American journalist Horace Greeley. However, they yielded to the insistence of the Schacht family grandmother, who firmly believed the child's given name should be Danish. After completing his Abitur at the Gelehrtenschule des Johanneums, Schacht studied medicine, philology, political science, and finance at the Universities of Munich, Leipzig, Berlin, Paris and Kiel before earning a doctorate at Kiel in 1899 – his thesis was on mercantilism.

He joined the Dresdner Bank in 1903. In 1905, while on a business trip to the United States with board members of the Dresdner Bank, Schacht met the famous American banker J. P. Morgan, as well as U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt. He became deputy director of the Dresdner Bank from 1908 to 1915. He was then a board member of the German National Bank for the next seven years, until 1922, and after its merger with the Darmstädter und Nationalbank (Danatbank), a board member of the Danatbank.

Schacht was a freemason, having joined the lodge Urania zur Unsterblichkeit in 1908.

During the First World War, Schacht was assigned to the staff of General Karl von Lumm (1864–1930), the Banking Commissioner for German-occupied Belgium, to organize the financing of Germany's purchases in Belgium. He was summarily dismissed by General von Lumm when it was discovered that he had used his previous employer, the Dresdner Bank, to channel the note remittances for nearly 500 million francs of Belgian national bonds destined to pay for the requisitions.

After Schacht's dismissal from public service, he had another brief stint at the Dresdner Bank, and then various positions at other banks. In 1923, Schacht applied and was rejected for the position of head of the Reichsbank, largely as a result of his dismissal from Lumm's service.

During the German Revolution of 1918–1919 Schacht became a Vernunftrepublikaner who had reservations over the parliamentary democratic system of the new Weimar Republic but supported it anyways for pragmatic reasons. He helped found the left-liberal German Democratic Party (DDP), which took a leading role in the governing Weimar Coalition. However, Schacht later became an ally of Gustav Stresemann, the leader of the center-right German People's Party (DVP).

Rise to president of the Reichsbank

Despite the blemish on his record from his service with von Lumm, in November 1923, Schacht became currency commissioner for the Weimar Republic and participated in the introduction of the Rentenmark, a new currency the value of which was based on a mortgage on all of the properties in Germany. Germany entered into a brief period where it had two separate currencies: the Reichsmark managed by Rudolf Havenstein, President of the Reichsbank, and the newly created Rentenmark managed by Schacht.

After his economic policies helped battle German hyperinflation and stabilize the German Reichsmark (Helferich Plan), Schacht was appointed president of the Reichsbank at the requests of president Friedrich Ebert and Chancellor Gustav Stresemann.

In 1926, Schacht provided funds for the formation of IG Farben. He collaborated with other prominent economists to form the 1929 Young Plan to modify the way that war reparations were paid after Germany's economy was destabilizing under the Dawes Plan. In December 1929, he caused the fall of the Finance Minister Rudolf Hilferding by imposing upon the government his conditions for obtaining a loan. After modifications by Hermann Müller's government to the Young Plan during the Second Conference of The Hague (January 1930), he resigned as Reichsbank president on 7 March 1930. During 1930, Schacht campaigned against the war reparations requirement in the United States.

Schacht became a friend of the Governor of the Bank of England, Montagu Norman, both men belonging to the Anglo-German Fellowship and the Bank for International Settlements. Norman was so close to the Schacht family that he was godfather to one of Schacht's grandchildren .

Involvement with the NSDAP (Nazi Party) and government

By 1926, Schacht had left the shrinking DDP and began increasingly lending his support to the Nazi Party (NSDAP). He became disillusioned with Stresemann's policies after he believed that closer relations with the United States were failing to provide economic benefits, and after his efforts to negotiate a rapprochement with the United Kingdom by pegging the Reichsmark to the pound sterling failed. Beginning in 1929 he increasingly criticized German foreign and financial policy since 1924 and demanded the restoration of Germany's former eastern territories and overseas colonies. Schacht became closer to the Nazis between 1930 and 1932. Though never a member of the NSDAP, Schacht helped to raise funds for the party after meeting with Adolf Hitler. Close for a short time to Heinrich Brüning's government, Schacht shifted to the right by entering the Harzburg Front in October 1931.

Schacht's disillusionment with the existing Weimar government did not indicate a particular shift in his overall philosophy, but rather arose primarily out of two issues:

- his objection to the inclusion of Social Democratic Party elements in the government, and the effect of their various construction and job-creation projects on public expenditures and borrowings (and the consequent undermining of the government's anti-inflation efforts);

- his desire to see Germany retake its place on the international stage, and his recognition that "as the powers became more involved in their own economic problems in 1931 and 1932 ... a strong government based on a broad national movement could use the existing conditions to regain Germany's sovereignty and equality as a world power."

Schacht believed that if the German government was ever to commence a wholesale reindustrialization and rearmament in spite of the restrictions imposed by Germany's treaty obligations, it would have to be during a period lacking clear international consensus among the Great Powers.

After the November 1932 elections, in which the NSDAP saw its vote share fall by four percentage points, Schacht and Wilhelm Keppler organized a petition of industrial and financial leaders, the Industrielleneingabe (Industrial petition), requesting president Paul Von Hindenburg to appoint Adolf Hitler as Chancellor. After Hitler took power in January 1933, Schacht won re-appointment as Reichsbank president on 17 March.

In August 1934 Hitler appointed Schacht as Germany's Reichsminister of Economics. Schacht supported public-works programs, most notably the construction of autobahnen (highways) to attempt to alleviate unemployment – policies which had been instituted in Germany by Kurt von Schleicher's government in late 1932, and had in turn influenced Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal in the United States. He also introduced the "New Plan", Germany's attempt to achieve economic "autarky", in September 1934. Germany had accrued a massive foreign currency deficit during the Great Depression, which continued into the early years of Nazi rule. Schacht negotiated several trade agreements with countries in South America and southeastern Europe, under which Germany would continue to receive raw materials, but would pay in Reichsmarks. This ensured that the deficit would not get any worse, while allowing the German government to deal with the gap which had already developed. Schacht also found an innovative solution to the problem of the government deficit by using mefo bills.

Schacht also was made a member of the Academy for German Law. He was appointed General Plenipotentiary for the War Economy in May 1935 by provision of the Reich Defense Law of 21 May 1935 and was awarded honorary membership in the NSDAP and the Golden Party Badge in January 1937.

Schacht disagreed with what he called "unlawful activities" against Germany's Jewish minority and in August 1935 made a speech denouncing Julius Streicher and Streicher's writing in the Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer.

During the economic crisis of 1935–36, Schacht, together with the Price Commissioner Dr. Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, helped lead the "free-market" faction in the German government. They urged Hitler to reduce military spending, turn away from autarkic and protectionist policies, and reduce state control in the economy. Schacht and Goerdeler were opposed by a faction centering on Hermann Göring.

Göring was appointed "Plenipotentiary for the Four Year Plan" on 18 October 1936, with broad powers that conflicted with Schacht's authority. Schacht objected to continued high military spending, which he believed would cause inflation, thus coming into conflict with Hitler and Göring.

In 1937 Schacht met with Chinese Finance Minister Dr. H. H. Kung. Schacht told him that "German-Chinese friendship stemmed in good part from the hard struggle of both for independence". Kung said, "China considers Germany its best friend ... I hope and wish that Germany will participate in supporting the further development of China, the opening up of its sources of raw materials, the upbuilding of its industries and means of transportation."

In November 1937 he resigned as Reichsminister of Economics and General Plenipotentiary at both his and Göring's request. He had grown increasingly dissatisfied with Göring's near-total ignorance of economics, and was also concerned that Germany was coming close to bankruptcy. Hitler, however, knew that Schacht's departure would raise eyebrows outside Germany, and insisted that he remain in the cabinet as minister without portfolio. He remained President of the Reichsbank until Hitler dismissed him in January 1939. He remained as a Reichsminister without Portfolio, and received the same salary, until he was fully dismissed in January 1943.

Following the Kristallnacht of November 1938, Schacht publicly declared his repugnance at the events, and suggested to Hitler that he should use other means if he wanted to be rid of the Jews. He put forward a plan in which Jewish property in Germany would be held in trust, and used as security for loans raised abroad, which would also be guaranteed by the German government. Funds would be made available for Jewish emigrants, in order to overcome the objections of countries that were hesitant to accept penniless Jews. Hitler accepted the suggestion, and authorised him to negotiate with his London contacts. Schacht, in his book The Magic of Money (1967), wrote that Montagu Norman and Lord Bearstead, a prominent Jew, had reacted favourably, but Chaim Weizmann, leading spokesman for the British Zionist Federation, opposed the plan. A component of the plan was that emigrating Jews would have taken items such as machinery with them on leaving the country, as a means of boosting German exports. The similar Haavara Agreement allowing German Jews to emigrate to Mandatory Palestine under similar terms had been signed in 1933.

Resistance activities

Schacht was said to be in contact with the German resistance to Nazism as early as 1934, though at that time he still believed the Nazi regime would follow his policies. By 1938, he was disillusioned, and was an active participant in the plans for a coup d'état against Hitler if he started a war against Czechoslovakia. Goerdeler, his colleague in 1935–36, was the civilian leader of resistance to Hitler. Schacht talked frequently with Hans Gisevius, another resistance figure; when resistance organizer Theodor Strünck's house (a frequent meeting place) was bombed out, Schacht allowed Strünck and his wife to live in a villa he owned. However, Schacht had remained in the government and, after 1941, Schacht took no active part in any resistance.

Still, at Schacht's denazification trial (subsequent to his acquittal at the Nuremberg trials) it was declared by a judge that "None of the civilians in the resistance did more or could have done more than Schacht actually did."

After the attempt on Hitler's life on 20 July 1944, Schacht was arrested on 23 July. He was sent to Ravensbrück, then to Flossenbürg, and finally to Dachau. In late April 1945 he and about 140 other prominent inmates of Dachau were transferred to Tyrol by the SS, which left them there. They were liberated by the Fifth U.S. Army on 5 May 1945 in Niederdorf, South Tyrol, Dolomites, Italy.

After the war

Schacht had supported Hitler's gaining power, and had been an important official of the Nazi regime. Thus he was arrested by the Allies in 1945. He was put on trial at Nuremberg for "conspiracy" and "crimes against peace" (planning and waging wars of aggression), but not war crimes or crimes against humanity.

Schacht pleaded not guilty to these charges. He cited in his defense that he had lost all official power before the war even began, that he had been in contact with Resistance leaders like Hans Gisevius throughout the war, and that he had been arrested and imprisoned in a concentration camp himself.

His defenders argued that he was just a patriot, trying to make the German economy strong. Furthermore, Schacht was not a member of the NSDAP and shared very little of their ideology. The British judges favored acquittal, while the Soviet judges wanted to convict. The British prevailed and Schacht was acquitted. However, at a West German denazification trial, Schacht was sentenced to eight years hard labor. He was freed on appeal in 1948.

In 1950, Juan Yarur Lolas, the Palestinian-born founder of the Banco de Crédito e Inversiones and president of the Arab colony in Santiago, Chile, tried to hire Schacht as a "financial adviser" in conjunction with the German-Chilean community. However, the plan fell through when it became news. He served as a hired consultant for Aristotle Onassis, a Greek businessman, during the 1950s. He also advised the Indonesian government in 1951 following the invitation of economic minister Sumitro Djojohadikusumo.

In 1953, Schacht started a bank, Deutsche Außenhandelsbank Schacht & Co., which he led until 1963. He also gave advice on economics and finance to heads of state of developing countries, in particular the Non-Aligned countries; however, some of his suggestions were opposed, one of which was in the Philippines by the former Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas head Miguel Cuaderno, who firmly rebuffed Schacht, stating that his monetary schemes were hardly appropriate for an economy needing capital investment in basic industry and infrastructure.

Indirectly resulting from his founding of the bank, Schacht was the plaintiff in a foundational case in German law on the "general right of personality". A magazine published an article criticizing Schacht, containing several incorrect statements. Schacht first requested that the magazine publish a correction, and when the magazine refused, sued the publisher for violation of his personality rights. The district court found the publisher both civilly and criminally liable; on appeal, the appellate court reversed the criminal conviction, but found that the publisher had violated Schacht's general right of personality.

Schacht died in Munich, West Germany, on 3 June 1970.

Works

Schacht wrote 26 books during his lifetime, of which at least four have been translated into English:

- The Stabilisation of the Mark (1927) ([1])

- The End of Reparations (J. Cape & H. Smith; 1931)

- Account Settled/Abrechnung mit Hitler (1949) after his acquittal at the Nuremberg Trials

- Confessions of the Old Wizard, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1956) ([2])

- The Magic of Money, (London: Oldbourne, 1967)

- My First Seventy-Six Years (autobiography), (Allan Wingate, 1955; online)

Miscellany

- Gustave Gilbert, an American Army psychologist, examined the Nazi leaders who were tried at Nuremberg. He administered a German version of the Wechsler-Bellevue IQ test. Schacht scored 143, the highest among the leaders tested, after adjustment upwards to take account of his age.

- When he stabilized the mark in 1923, Schacht's office was a former charwoman's cupboard. When his secretary, Fräulein Steffeck, was later asked about his work there. She described it as follows:

-

- What did he do? He sat on his chair and smoked in his little dark room which still smelled of old floor cloths. Did he read letters? No, he read no letters. Did he write letters? No, he wrote no letters. He telephoned a great deal – he telephoned in every direction and to every German or foreign place that had anything to do with money and foreign exchange as well as with the Reichsbank and the Finance Minister. And he smoked. We did not eat much during that time. We usually went home late, often by the last suburban train, travelling third class. Apart from that he did nothing.

See also

In Spanish: Hjalmar Schacht para niños

In Spanish: Hjalmar Schacht para niños

- Secret Meeting of 20 February 1933