Hotel Chelsea facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Hotel Chelsea |

|

|---|---|

Seen from across 23rd Street

|

|

| Alternative names | Chelsea Hotel |

| Etymology | The neighborhood of Chelsea, Manhattan |

| General information | |

| Type | Hotel |

| Architectural style | Queen Anne Revival, Victorian Gothic |

| Address | 222 West 23rd Street, Manhattan, New York, U.S. |

| Coordinates | 40°44′40″N 73°59′49″W / 40.74444°N 73.99694°W |

| Construction started | 1883 |

| Opened | 1884 |

| Renovated |

|

| Owner | Chelsea Hotel Owner LLC |

| Management | BD Hotels |

| Height | 180 ft (55 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 12 |

| Grounds | 17,281 sq ft (1,605.5 m2) |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Philip Hubert |

| Architecture firm | Hubert, Pirsson & Co. |

| Developer | Chelsea Association |

| Other information | |

| Number of rooms | 155 (125 hotel rooms, 30 suites) |

|

Hotel Chelsea

|

|

| Location | 222 West 23rd Street Chelsea, Manhattan, New York City |

| Built | 1883–1884 |

| Architect | Hubert, Pirsson and Company |

| Architectural style | Queen Anne Revival, Victorian Gothic |

| NRHP reference No. | 77000958 |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | December 27, 1977 |

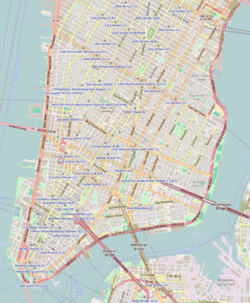

The Hotel Chelsea – also called the Chelsea Hotel, or simply the Chelsea – is a hotel in Manhattan, New York City, built between 1883 and 1885. The 250-unit hotel is located at 222 West 23rd Street, between Seventh and Eighth Avenues, in the neighborhood of Chelsea.

It has been the home of numerous writers, musicians, artists and actors. Though the Chelsea no longer accepts new long-term residents, the building is still home to many who lived there before the change in policy. Arthur C. Clarke wrote 2001: A Space Odyssey while staying at the Chelsea, and poets Allen Ginsberg and Gregory Corso chose it as a place for philosophical and artistic exchange. It is also known as the place where the writer Dylan Thomas was staying in room 205 when he became ill and died several days later, in a local hospital, of pneumonia on November 9, 1953. Arthur Miller wrote a short piece, "The Chelsea Affect", describing life at the Chelsea Hotel in the early 1960s.

The building has been a designated New York City landmark since 1966, and on the National Register of Historic Places since 1977.

Contents

History

Built between 1884 and 1885 and opened for initial occupation in 1884, the twelve-story red-brick building that is now the Hotel Chelsea was one of the city's first private apartment cooperatives. It was designed by Philip Hubert of the firm of Hubert, Pirrson & Company in a style that has been described variously as Queen Anne Revival and Victorian Gothic. Among its distinctive features are the delicate, flower-ornamented iron balconies on its facade, which were constructed by J.B. and J.M. Cornell and its grand staircase, which extends upward twelve floors. Generally, this staircase is only accessible to registered guests, although the hotel does offer monthly tours to others. At the time of its construction, the building was the tallest in New York.

Hubert and Pirsson had created a "Hubert Home Club" in 1880 for "The Rembrandt," a six-story building on West 57th Street intended as housing for artists. This early cooperative building had rental units to help defray costs, and also provided servants as part of the building staff. The success of this model led to other "Hubert Home Clubs," and the Chelsea was one of them. Initially successful, its surrounding neighborhood constituted the center of New York's theater district. However, within a few years the combination of economic stresses, the suspicions of New York's middle class about apartment living, the opening up of Upper Manhattan and the plentiful supply of houses there, and the relocation of the city's theater district bankrupted the Chelsea.

The building reopened as a hotel in 1905, which was later managed by Knott Hotels and resident manager A. R. Walty. After the hotel went bankrupt, it was purchased in 1939 by Joseph Gross, Julius Krauss, and David Bard, and these partners managed the hotel together until the early 1970s. Stanley Bard, David Bard's son, became manager after Gross and Krauss' deaths.

On June 18, 2007, the hotel's board of directors ousted Bard as the hotel's manager. Dr. Marlene Krauss, the daughter of Julius Krauss, and David Elder, the grandson of Joseph Gross and the son of playwright and screenwriter Lonne Elder III, replaced Stanley Bard with the management company BD Hotels NY; that firm has since been terminated as well.

The hotel was sold to real estate developer Joseph Chetrit for $80 million in 2011 and stopped taking reservations for new guests, to begin renovations. Long-time residents were allowed to remain in the building, some of them protected by state rent regulations. The renovations prompted complaints to the city by the remaining tenants of health hazards caused by the construction. The city's Building Department investigated these complaints and found no major violations. In November 2011, the management ordered all of the hotel's many artworks taken off the walls, supposedly for their protection and cataloging, a move which some tenants interpreted as a step towards forcing them out as well. In 2013, Ed Scheetz became the Chelsea Hotel's new owner after buying back five properties from Chetrit and David Bistricer.

Located in the Chelsea since 1930 is the restaurant El Quijote which was owned by the same family until 2017 when it was sold to the new owner of the hotel. In late March 2018 the eatery also closed for renovations.

The hotel fully reopened in mid-2022. At the time, there were still 40 permanent residents, and the cheapest suite cost $700 per night.

Notable residents

Over the years, the Chelsea has become particularly well-known for its residents, who have come from all social classes. The New York Times described the hotel in 2001 as a "roof for creative heads", given the large number of such personalities who have stayed at the Chelsea; the previous year, the same newspaper had characterized the list of tenants as "living history". The journalist Pete Hamill characterized the hotel's clientele as "radicals in the 1930s, British sailors in the 40s, Beats in the 50s, hippies in the 60s, decadent poseurs in the 70s". Although early tenants were wealthy, the Chelsea attracted less well-off tenants by the mid-20th century, and many writers, musicians, and artists lived at the Hotel Chelsea when they were short on money. Accordingly, the Chelsea's guest list had almost zero overlap with that of the more fashionable Plaza Hotel crosstown.

New York magazine wrote that "people who lived in the hotel slept together as often as they celebrated holidays together", particularly under Stanley Bard's tenure. Despite the high number of notable people associated with the Chelsea, its residents typically desired privacy and frowned upon those who used their relationships with their neighbors to further their own careers.

Literature

The Hotel Chelsea has housed numerous literary figures, some of whom wrote their books there. Arthur C. Clarke wrote 2001: A Space Odyssey while staying at the Chelsea, calling the hotel his "spiritual home" despite its condition. Thomas Wolfe lived in the hotel before his death in 1938, writing several books such as You Can't Go Home Again; he often walked around the halls to gain inspiration for his writing. William S. Burroughs, who also lived at the Chelsea, wrote his book Naked Lunch there. While living at the Chelsea, Edgar Lee Masters wrote 18 poetry books, often wandering the hotel for hours.

Welsh poet Dylan Thomas (who lived with his wife Caitlin Thomas) was staying in room 205 when he became ill and died in 1953, while American poet Delmore Schwartz spent the last few years of his life in seclusion at the Chelsea before he died in 1966. Irish poet Brendan Behan lived at the hotel for several months before his death in 1964. Many poets of the Beat poetry movement also lived at the Chelsea before the Beat Hotel in Paris became popular.

Other authors, writers, and journalists who stayed or lived at the hotel have included:

- Henry Abbey, poet

- Nelson Algren, writer

- Léonie Adams, poet; lived with husband William Troy

- Sherwood Anderson, writer

- Ben Lucien Burman, writer

- Henri Chopin, poet and musician

- Ira Cohen, poet and filmmaker

- Gregory Corso, poet

- Hart Crane, poet

- Quentin Crisp, writer and actor

- Jane Cunningham Croly, journalist

- Katherine Dunn, novelist and journalist

- Edward Eggleston, writer

- James T. Farrell, novelist

- Allen Ginsberg, poet

- John Giorno, poet

- Maurice Girodias, publisher

- Pete Hamill, journalist

- Bernard Heidsieck, poet

- O. Henry, writer

- Herbert Huncke, poet

- Clifford Irving, novelist and reporter

- Charles R. Jackson, author

- Theodora Keogh, novelist

- Jack Kerouac, writer

- Suzanne La Follette, journalist

- John La Touche, lyricist

- Jakov Lind, novelist

- Mary McCarthy, novelist and political activist

- Arthur Miller, playwright

- Jessica Mitford, author

- Vladimir Nabokov, novelist

- Eugene O'Neill, playwright

- Joseph O'Neill, novelist

- Claude Pélieu, poet and artist

- Rene Ricard, poet

- James Schuyler, poet

- Sam Shepard, playwright and actor

- Valerie Solanas, writer

- Benjamin Stolberg, publicist and author

- Richard Suskind, children's writer

- William Troy, critic; lived with wife Léonie Adams

- Mark Twain, writer

- Gore Vidal, writer

- Arnold Weinstein, librettist

- Tennessee Williams, playwright

- Yevgeny Yevtushenko, poet

Entertainers

The hotel has been home to actors, film directors, producers, and comedians. The actress Sara Lowndes moved to a room adjoining that of musician Bob Dylan before the two married in 1965. Edie Sedgwick, an actress and Warhol superstar, set her room on fire by accident in 1967, while Viva, another Warhol superstar, lived at the Chelsea with her daughter Gaby Hoffmann. Members of the Squat Theatre Company also stayed in the hotel in the 1970s while performing nearby.

Other entertainment personalities who lived or stayed at the Chelsea include:

- Martine Barrat, filmmaker

- Sarah Bernhardt, actress, slept in a custom coffin

- Russell Brand, actor and comedian

- Peter Brook, director

- Shirley Clarke, filmmaker

- Laura Sedgwick Collins, actress

- Bette Davis, actress

- Abel Ferrara, filmmaker

- Jane Fonda, actress

- Miloš Forman, filmmaker

- Ethan Hawke, actor and film director

- Mitch Hedberg, comedian

- Dave Hill, comedian

- Dennis Hopper, filmmaker

- John Houseman, actor, lived in a penthouse

- Michael Imperioli, actor

- Eddie Izzard, comedian

- Stanley Kubrick, director

- Lillie Langtry, actress

- Carl Lee, actor

- Gerard Malanga, actor, filmmaker, poet, and musician

- Jonas Mekas, filmmaker

- Ondine, actor

- Al Pacino, actor

- Isabella Rossellini, actress

- Annie Russell, actress

- Lillian Russell, actress

- Elaine Stritch, actress

- Donald Sutherland, actor

- Eva Tanguay, actress

- Aurélia Thierrée, actress

- Rosa von Praunheim, filmmaker

- Mary Woronov, actress

Musicians

Composer and critic Virgil Thomson, once described by The New York Times as the hotel's "most illustrious tenant", lived at the hotel for nearly five decades before his death in 1989. The composer George Kleinsinger lived with his pet animals on the tenth floor. The activist Stormé DeLarverie was also a long-term resident, as was the drag queen Candy Darling.

The Chelsea was particularly popular among rock musicians and rock and roll musicians in the 1970s. These included Sid Vicious of the Sex Pistols. Numerous rock bands frequented the Chelsea as well, including the Allman Brothers, the Band, Big Brother and the Holding Company, the Paul Butterfield Blues Band, the Byrds, Country Joe and the Fish, Jefferson Airplane, Lovin' Spoonful, Moby Grape, the Mothers of Invention, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Sly and the Family Stone, and the Stooges. The Kills wrote much of their album No Wow at the Chelsea prior to its release in 2005. The Grateful Dead once performed on the roof.

Other prominent musical acts that stayed in the Chelsea include:

- Ryan Adams, singer-songwriter

- Joan Baez, folk musician

- Chet Baker, jazz trumpeter and vocalist

- John Cale, musician, composer, and record producer

- Leonard Cohen, singer-songwriter

- Alice Cooper, rock singer

- Chick Corea, composer, pianist, keyboardist, bandleader, and percussionist

- Julie Delpy, actress and songwriter

- Donovan, multi-instrumentalist and songwriter

- Bob Dylan, singer-songwriter

- Marianne Faithfull, rock singer

- Jimi Hendrix, guitarist

- Abdullah Ibrahim, pianist and composer

- Janis Joplin, singer

- Jobriath, singer

- Madonna, singer and actress;

- Bette Midler, actress

- Buddy Miles, drummer and singer

- Joni Mitchell, singer-songwriter

- Jim Morrison, singer-songwriter

- Nico, singer

- Phil Ochs, songwriter

- Édith Piaf, singer

- Iggy Pop, rock musician

- Dee Dee Ramone, punk rock musician

- Robbie Robertson, singer-songwriter and guitarist

- Ravi Shankar, musician

- Patti Smith, singer

- Johnny Thunders, guitarist and singer-songwriter

- Rufus Wainwright, singer-songwriter and composer

- Tom Waits, jazz musician, composer, songwriter

- Edgar Winter, multi-instrumentalist

- Johnny Winter, guitarist and singer

- Frank Zappa, guitarist, composer, and bandleader

Visual artists

Many visual artists, including painters, sculptors, and photographers, have resided at the Chelsea. The painter John Sloan lived in one of the top-floor duplexes until his death in 1951, painting portraits of both the Chelsea and nearby buildings. Joseph Glasco lived at the Chelsea in 1949 and then lived there on recurring visits and painted Chelsea Hotel (1992) there. During the 1960s, acolytes of the polymath Harry Everett Smith frequently gathered around his apartment. The painter Alphaeus Philemon Cole lived there for 35 years until his death in 1988 when, at the age of 112, he was the oldest verified man alive. The artist Vali Myers lived at the hotel from 1971 to 2014, while conceptual artist Bettina Grossman lived in the Chelsea from 1970 to her death in 2021. Although Andy Warhol never lived in the hotel, many of his associates did.

Other artists who have lived at the Chelsea include:

- Joe Andoe, painter

- Karel Appel, painter and sculptor

- Arman, painter

- Brigid Berlin, artist and Warhol superstar

- Robert Blackburn, printmaker

- Arthur Bowen Davies, painter

- Frank Bowling, painter

- Henri Cartier-Bresson, photographer

- Doris Chase, video artist

- Ching Ho Cheng, painter

- Bernard Childs, painter

- Christo and Jeanne-Claude, installation artists

- Francesco Clemente, artist

- Robert Crumb, cartoonist

- Charles Melville Dewey, painter

- Jim Dine, artist

- Claudio Edinger, photographer

- William Eggleston, photographer

- Jorge Fick, mixed-media artist

- André François, cartoonist

- Herbert Gentry, artist

- Alberto Giacometti, painter

- Joseph Glasco, abstract artist

- Brion Gysin, multimedia artist

- Childe Hassam, painter

- David Hockney, artist

- Alain Jacquet, artist

- Jasper Johns, painter, sculptor, draftsman, and printmaker

- Leo Katz, muralist

- Yves Klein, artist

- Willem de Kooning, painter

- Nicola L, multidisciplinary artist

- Ryah Ludins, painter

- Robert Mapplethorpe. photographer; lived with Patti Smith

- Inge Morath, photographer

- Charles R. Macauley, cartoonist

- Maryan S. Maryan, post-expressionist painter; died in his hotel room in 1977

- Kenneth Noland, abstract painter

- Claes Oldenburg, sculptor

- Elizabeth Peyton, contemporary artist

- Jackson Pollock, abstract painter

- Martial Raysse, artist

- David Remfry, painter

- Diego Rivera, artist

- Larry Rivers, artist

- Mark Rothko, abstract painter

- Niki de Saint Phalle, sculptor, painter, and filmmaker

- Julian Schnabel, artist

- Moses Soyer, painter; died in his studio in 1974

- Philip Taaffe, artist; lived in Virgil Thompson's old apartment

- Jean Tinguely, sculptor

- Nahum Tschacbasov, expressionist artist

- Stella Waitzkin, artist

- Tom Wesselmann, artist

- Brett Whiteley, artist

- Rufus Fairchild Zogbaum, painter

Other figures

One early resident of the Chelsea, U.S. congressman-elect Andrew J. Campbell, died at his apartment in 1894 before he could be sworn in. The choreographer Katherine Dunham, who rehearsed at the hotel in the 1960s, was one of the few dance–associated figures to stay in the Chelsea. Communist Party USA leader Elizabeth Gurley Flynn lived at the hotel, as did event producer Susanne Bartsch.

Several fashion designers have lived at the Chelsea. Charles James, credited with being America's first couturier who influenced fashion in the 1940s and 1950s, moved into the Chelsea in 1964. The designer Elizabeth Hawes lived in the Chelsea until her death in 1971. Billy Reid used one of the Chelsea's rooms as an office, studio, and showroom starting in 1998. After returning to New York City in 2001, Natalie "Alabama" Chanin briefly lived in the Chelsea Hotel.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Hotel Chelsea para niños

In Spanish: Hotel Chelsea para niños