Indian Muslims in the 1857 Rebellion facts for kids

The Indian Rebellion of 1857, which was also known as the Sepoy Mutiny or the First War of Independence, and was a significant uprising against British colonial rule in India from 1857 to 1858, was directed against the authority of the British East India Company, which acted as a self-governing entity on behalf of the British Crown. The rebellion originated on 10 May 1857 when sepoys, Indian soldiers, mutinied in Meerut, a garrison town northeast of Delhi. It quickly spread across the upper Gangetic plain and central India, with additional instances of revolt in the northern and eastern regions.

Muslim soldiers, known as sepoys, were instrumental in igniting the rebellion, driven by rumors that the cartridges for their rifles were greased with animal fat, which offended their religious beliefs. In regions such as Awadh, Delhi, Bihar, and Bengal, Muslim leaders emerged as key figures in the uprising. Prominent figures like Bahadur Shah II, the last Mughal emperor, and Maulvi Ahmadullah Shah led significant uprisings against the British, symbolizing a desire for the restoration of Muslim political power.

Contents

Factors

Military Employment

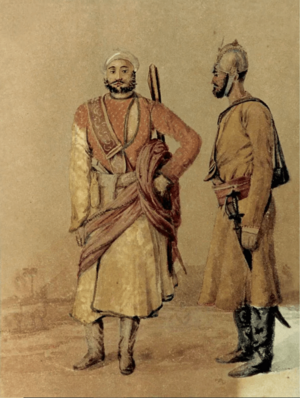

Unemployed Muslim horsemen joined the East India Company's army after the end of Muslim rule under irregular cavalry units that preserved Mughal cavalry traditions and were raised under the silladar system, primarily recruiting Hindustani Musalman biradaris such as the Sayyids, Ranghars, Shaikhs, Mughals and Hindustani Pathans who made up three-quarters of the British army's cavalry. This had a political purpose as it employed swathes of cavalrymen who would otherwise have been disaffected plunderers. However, as not all of these cavalrymen could be employed, partly as few were attracted to the discipline of the British military, many turned to mercenary activity such as the Pindaris, or were unemployed, leading to disaffection. For many Indian Muslims of this class, British conquest meant a destruction of a way of life as much as a destruction of a livelihood.

Ancestral Allegiance

According to Bates, Indian Muslim families who had for generations served the throne, such as the Barha Sadaat tribe of Muzaffarnagar, who had long produced Mansabdars (Mughal aristocrats), had developed a relationship of mutual respect between themselves and the throne which British rule had failed to replicate with its subjects. For example, this relationship forced Sayyid Ghulam Abbas, a Baraha Sayyid, to resign as a Sowar from the "Regiment IV in the British Army" to join the Mughal Emperor, although the latter had nothing to offer him:

"I have resigned and reached here on 29th Shawwal/ 12th June, 1857 to join your service because my ancestors had also served the Mughal Emperors. Now I am waiting when my prayer will be fulfilled."

In the point of view of the rebels, the restoration of the legitimate mughal sovereign was the return of the rightful chiefs of Hindustan to their respective positions. The insurgents did not describe themselves as 'rebels', rather they called themselves 'servants of the King of Delhi'. Instead, the British were referred to as "Baghi", or as usurpers who were thrown out for the highest to be restored to their legitimate superior status.

Religious Sentiment

Religion's role in the 1857 rebellion in North India has been debated for years. Early British sources suggest that religious grievances and transgressions by the East India Company played the primary role in the Mutiny, as the introduction of the Enfield Rifle and its pork cartridges were considered a religious offense to the Muslims. However, later scholarship tended to focus on non-religious grievances such as socio-economic issues, largely influenced by the prevalence of Marxism in late Indian historiography, as well as scholarly caution when dealing with orientalism in Western readings of the past. However this trend was reversed abruptly in recent scholarship, such as William Dalrymple's book The Last Mughal, has emphasized the role of religion in the rebellion, which particularly cite largely untapped Urdu sources, which frequently mention Nasrani(Christian) and Kafir(infidel) instead of Firangi(European) as the enemies of the king. An important distinction made by Dalrymple was that previous British converts to Islam were spared of the violence, while Indian converts to Christianity, including one of Bahadur Shah II's own physicians, Chaman Lal, were killed en masse.

Roles

Mutineers

Indian Muslims made up 75% of the Native Cavalry, as opposed to Hindus who made 80% of the infantry. In the British Indian artillery, North Indian MusIims were also generaIIy preferred and made the majority of the establishment, as unlike the Hindus, Indian Muslims were willing to fight overseas. The Sowars of the 3rd Native Cavalry, who had started the caused the catalyst for the war by being the first to break out in Mutiny in Meerut, were largely composed of Indian Muslims. These Sowars rode off from Meerut to Delhi to set up Bahadur Shah II as the head of the rebellion. While they retained significant organizational and hierarchical elements of the British army in which they had been trained, Indian Muslim military groups often took steps to adopt Islamic garb to distinguish themselves from the ranks of the loyal sepoys.

Leadership

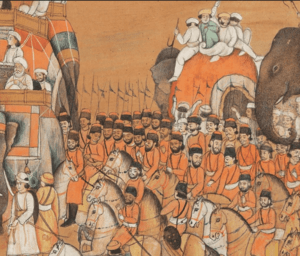

Bahadur Shah II, who was initially bewildered, was persuaded to hold a durbar, the first in years, to show that the Mughal Empire had returned. A working constitution, the Dastarul Amal was drawn up. Bahadur Shah II finalized positions for many of his sons and relations, and wrote letters to the regional rulers asking to join his troops against the English. A military and civilian management committee was formed. Nawab Aminuddin Ahmad Khan and his brother Ziauddin Khan, Nawabs of Loharu near Delhi were summoned to the Delhi court and received orders to occupy the Firozpur Jhirka. Despite Bahadur Shah's insistence of his reluctance during the later trials, an account by Munshi Mohan Lal offered a different picture, where Bahadur Shah II had become more actively involved in the movement of troops in the city. Bahadur Shah II's increasing openness to the Uprising, although never entirely wholehearted and always ambivalent, nevertheless changed the whole nature of the rebellion. A militant strain can be seen in Bahadur Shah II's own works:

O Allah, may the enemy troops be all killed

May the Gurkhas, Whites, Gujars and Englishmen be all killed

We shall recognize this day as the Festival of Sacrifice only when

O Zafar, your murderer be put to the sword today!

One of Bahadur Shah's sons, Mirza Mughal, the maternal son of a Sayyida, had already been in contact with discontent troops in the colonial army since 1856. From 12 May onwards, he became the principal rebel leader within the royal family, and worked with great industry to keep the Delhi administration running amid the chaos of the rebellion and the siege. Until his supersession after the arrival of Bakht Khan, he was made commander-in-chief of the initial rebel soldiers, and sought energetically to organize the troops. Mirza Mughal constructed an elaborate system of barricades and street defences, including a damdama in front of the Kashmir Gate, realizing that once the British were within the walls, their troops would be far more vulnerable than they would be behind their carefully built breastworks on the Ridge. He encouraged the British to leave their impregnable entrenchments and lure them into the city streets. On the other hand, Mirza Khizr Sultan was frequently criticized for corruption, making arrests and collecting taxes from the town bankers without authority to do so. Bakht Khan who had been elected general by the Bareilly troops and had arrived in Delhi, with a reputation as both of an administrator and an effective military leader.

Feudal Lords

The outbreak of the revolt in Meerut lighted a tinderbox, and although the uprisings did not occur all in the same manner, the type and pattern were largely the same, which was quickly felt in the whole of the North-Western Provinces and especially in the Doab which was a scene of a succession of mutinies excited by the same impulse. The uprising in Muzaffarnagar was led by Khaitati Khan Pindari, the noted rebel of the Kandhla pargana. The failed expedition and the initial reverses of the British troops turned the rising into a vast upsurge of the several villages of the southwestern part of the tahsil. Khairati Khan even captured the fort of Budhana to the east of Kandhla. Meanwhile, Inayat Ali Khan led the Indian Muslim uprising in Thana Bhawan, which was joined especially by the disaffected Shaikhzadas. The most formidable rising of the Muslim insurrections in Aligarh was by Ghiyasuddin Muhammad Khan, who raised the green flag, proclaimed himself the subahdar in the name of the king of Delhi, collected revenue and exercised the prerogatives of royalty. His field insurgents numbered five to six thousand besides a mixed body of sepoys and zamindari levies amounting to six or seven hundred men. In the district of Saharanpur, civil rebellion preceded the mutiny, where the population of the town amounted to about forty thousand most of whom were Indian Muslims. The mutiny of troops was less in evidence than the risings of the Gujjars and Muslim Ranghars who broke out in revolt on the news of the Meerut outbreak as well as the fall of Delhi and Muzaffarnagar. The Ranghars of this district were exceptionally hostile, although they were generally wealthy so that plunder could hardly be their indcument to disaffection. A huge ranghar gathering resisted the British offensive in June 26. In the town of Sikandarabad in Bulandshahr, the leader of the rebels was Walidad Khan who held the fort of Malagarh. His levies were drawn from disaffected Gujjars as well as the Indian Pathans of Barabasti. Abdul Latif Khan, another leader of the Barrah Basti pathans, his uncle Azim Khan, as well as his nephew Hajee Munir Khan, joined Walidad Khan. Abdul Latif Khan was later executed. Tafazzal Hussain, the Nawab of Farrukhabad consolidated his newly gained power in a broad-based government consisting of Ashraf Khan, Multan Khan, Hyder Ali and Mohammad Taki. In the district of Rohilkhand, where Indian Muslim influence was strong, large numbers of dissolute, desperate and distressed Muslims who had lineage to boast of, and old traditions to excite them, were easily disposed to rebellion.

Ghazis

British sources testify to the presence of green religious flags that acted as a call to arms and as a counterpoint to the regimental standards of the rebel army. One of the best descriptions of a ghazi force is that supplied by Forbes-MItchell, who described their dress as a "thick quilted tunic of green silk...with green turbans and kummerbunds(Cummerbund), round shields on the left arm, and curved tulwars". According to British sources, the ghazis were "far more difficult to deal with than mutinous sepoys." The Maulvi of Faizabad, Ahmad Allah Shah, who was a natural leader of men, harassed the forces of Sir Colin Campbell during the hot season's campaign in 1858 for the conquest of Awadh. One Maulana Rahmat Allah assumed leadership of the revolt in Muzaffarnagar. In Shamli, the Sunnis chose Imdadullah Muhajir Makki as their leader. Bakht Khan's Jihadis including Imdad Ali Khan, accompanied by Maulvi Nawazish Khan with 2,000 men, were said to have made use of axes, and to have displayed particular bravery despite being surrounded. Among the Ghazis were British converts to Islam, namely Sergeant Gordon, who had been brought by the rebels of Shahjahanpur, who had 'laid and fired guns against the English batteries." According to Sa'id Mubarak Shah, upon the failure of the mutiny, Gorgon remarked that "It is impossible, but I will die along with you. Maulvi Sarfaraz Ali, who was known as the "Imam of the Mujahedin", who was well connected to both the court and city of Delhi for many years, and was singled out by Syed Ahmad Khan for praise as one of the brightest jewels in Delhi's intellectual crown, was considered to be along with Bakht Khan a symbol of unity between the Jihadis and the Delhi elite.

Repercussions

In those parts of India where the Muslim participation in the Mutiny was clear enough, such as Delhi and UP, it was natural for local British commanders and observers to be conscious of a strong Muslim tinge in the rebellion. The Urdu poet Ghalib wrote to a friend: "The very particles of dust in Delhi thirst for the blood of Muslims." British characterizations of Muslims as fanatics took the fore during and after the Great Rebellion, as well as produced the Indian Muslims as a unified, cogent group, who were easily agitated, aggressive, and inherently disloyal. An example of this was John Lawrence's letter to the Governor-General, Lord canning:

The Mahomedans of the Regular Cavalry when they have broken out have displayed a more active, vindictive, and fanatic spirit than the Hindoos - but these traits are characteristics of that race.

On the other hand, Sayyid Ahmad Khan pushed the idea that Hindus were the real instigators of the rebellion while the Muslims were innocent dupes with the most to lose in the war.