J. Edgar Hoover facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

J. Edgar Hoover

|

|

|---|---|

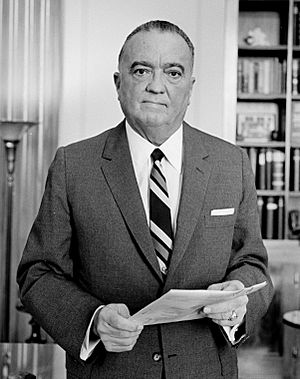

J. Edgar Hoover in September 1961

|

|

| 1st Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation | |

| In office March 22, 1935 – May 2, 1972 |

|

| President | Franklin D. Roosevelt Harry S. Truman Dwight D. Eisenhower John F. Kennedy Lyndon B. Johnson Richard Nixon |

| Deputy | Clyde Tolson |

| Preceded by | Office created (was BOI director) |

| Succeeded by | L. Patrick Gray (Acting) |

| 6th Director of the Bureau of Investigation | |

| In office May 10, 1924 – March 22, 1935 |

|

| President | Calvin Coolidge Herbert Hoover Franklin D. Roosevelt |

| Preceded by | William J. Burns |

| Succeeded by | Himself (as FBI Director) |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

John Edgar Hoover

January 1, 1895 Washington, D.C. United States |

| Died | May 2, 1972 (aged 77) Washington, D.C. United States |

| Alma mater | George Washington University |

| Signature | |

John Edgar Hoover (January 1, 1895 – May 2, 1972), was an American detective and the first Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) of the United States. He was appointed as the director of the Bureau of Investigation — the FBI's predecessor — in 1924 and was instrumental in founding the FBI in 1935, where he remained director until his death in 1972 at the age of 77. Hoover has been credited with building the FBI into a larger crime-fighting agency than it was at its inception and with instituting a number of modernizations to police technology, such as a centralized fingerprint file and forensic laboratories.

Later in life and after his death, Hoover became a controversial figure as evidence of his secretive abuses of power began to surface. He was found to have exceeded the jurisdiction of the FBI, and to have used the FBI to harass political dissenters and activists, to amass secret files on political leaders, and to collect evidence using illegal methods. Hoover consequently amassed a great deal of power and was in a position to intimidate and threaten sitting presidents.

Contents

Early life and education

John Edgar Hoover was born on New Year's Day 1895 in Washington, D.C., to Anna Marie (née Scheitlin; 1860–1938), who was of Swiss-German descent, and Dickerson Naylor Hoover, Sr. (1856–1921), who was of English and German ancestry. Hoover's maternal great-uncle, John Hitz, was a Swiss honorary consul general to the United States. Among his family, he was the closest to his mother, who was their moral guide and disciplinarian.

Hoover did not have a birth certificate filed upon his birth, although it was required in 1895 in Washington. Two of his siblings did have certificates, but Hoover's was not filed until 1938 when he was 43.

Hoover lived in Washington, D.C. for his entire life. He grew up near the Eastern Market in Washington's Capitol Hill neighborhood and attended Central High School, where he sang in the school choir, participated in the Reserve Officers' Training Corps program, and competed on the debate team. During debates, he argued against women getting the right to vote and against the abolition of the death penalty. The school newspaper applauded his "cool, relentless logic." Hoover stuttered as a boy, which he overcame by teaching himself to talk quickly—a style that he carried through his adult career. He eventually spoke with such ferocious speed that stenographers had a hard time following him.

Head of the Bureau of Investigation

In 1921, Hoover rose in the Bureau of Investigation to deputy head and, in 1924, the Attorney General made him the acting director. On May 10, 1924, President Calvin Coolidge appointed Hoover as the fifth Director of the Bureau of Investigation, partly in response to allegations that the prior director, William J. Burns, was involved in the Teapot Dome scandal. When Hoover took over the Bureau of Investigation, it had approximately 650 employees, including 441 Special Agents.

Hoover was sometimes unpredictable in his leadership. He frequently fired Bureau agents. He also relocated agents who had displeased him to career-ending assignments and locations. Melvin Purvis was a prime example: Purvis was one of the most effective agents in capturing and breaking up 1930s gangs, and it is alleged that Hoover maneuvered him out of the Bureau because he was envious of the substantial public recognition Purvis received.

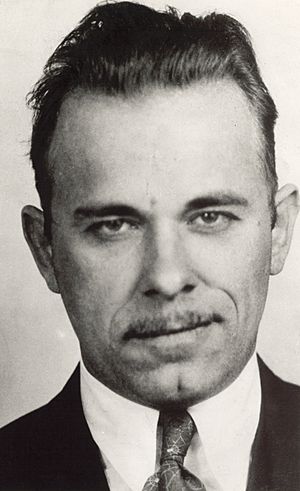

Depression-era gangsters

In the early 1930s, criminal gangs carried out large numbers of bank robberies in the Midwest. They used their superior firepower and fast getaway cars to elude local law enforcement agencies and avoid arrest. Many of these criminals frequently made newspaper headlines across the United States, particularly John Dillinger, who became famous for leaping over bank cages, and repeatedly escaping from jails and police traps. The gangsters enjoyed a level of sympathy in the Midwest, as banks and bankers were widely seen as oppressors of common people during the Great Depression.

The robbers operated across state lines, and Hoover pressed to have their crimes recognized as federal offenses so that he and his men would have the authority to pursue them and get the credit for capturing them. In late July 1934, Special Agent Melvin Purvis, the Director of Operations in the Chicago office, received a tip on Dillinger's whereabouts that paid off when Dillinger was located, ambushed, and killed by Bureau agents outside the Biograph Theater.

Hoover was credited with several highly publicized captures or shootings of outlaws and bank robbers, even though he was not present at the events. These included those of Machine Gun Kelly in 1933, of Dillinger in 1934, and of Alvin Karpis in 1936, which led to the Bureau's powers being broadened.

In 1935, the Bureau of Investigation was renamed the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). In 1939, the FBI became pre-eminent in the field of domestic intelligence, thanks in large part to changes made by Hoover, such as expanding and combining fingerprint files in the Identification Division, to compile the largest collection of fingerprints to date, and Hoover's help to expand the FBI's recruitment and create the FBI Laboratory, a division established in 1932 to examine and analyze evidence found by the FBI.

American Mafia

During the 1930s Hoover persistently denied the existence of organized crime, even while there were numerous shootings as a result of Mafia control of and competition over the Prohibition-created black-market.

While Hoover had fought bank-robbing gangsters in the 1930s, anti-communism was a bigger focus for him after World War II, as the Cold War developed. During the 1940s through mid-1950s, he seemed to ignore organized crime. He denied that any Mafia operated in the U.S. In the 1950s, evidence of Hoover's unwillingness to focus FBI resources on the Mafia became useful material, especially to support an argument for the media.

Hoover was concerned about what he claimed was subversion, and under his leadership, the FBI investigated tens of thousands of suspected subversives and radicals. According to critics, Hoover tended to exaggerate the dangers of these alleged subversives and many times overstepped his bounds in his pursuit of eliminating that perceived threat.

Florida and Long Island U-boat landings

The FBI investigated rings of German saboteurs and spies starting in the late 1930s, and had primary responsibility for counterespionage. The first arrests of German agents were made in 1938 and continued throughout World War II. In the Quirin affair, during World War II, German U-boats set two small groups of Nazi agents ashore in Florida and Long Island to cause acts of sabotage within the country. The two teams were apprehended after one of the men contacted the FBI and told them everything. He was also charged and convicted.

During this time period President Roosevelt, out of concern over Nazi agents in the United States, gave “qualified permission” to wiretap persons “suspected ... [of] subversive activities”. He went on to add, in 1941, that the United States Attorney General had to be informed of its use in each case. The Attorney General Robert H. Jackson left it to Hoover to decide how and when to use wiretaps, as he found the “whole business” distasteful.

Concealed espionage discoveries

The FBI participated in the Venona Project, a pre-World War II joint project with the British to eavesdrop on Soviet spies in the UK and the United States. They did not initially realize that espionage was being committed, but the Soviet's multiple use of one-time pad ciphers (which with single use are unbreakable) created redundancies that allowed some intercepts to be decoded. These established that espionage was being carried out.

Hoover kept the intercepts – America's greatest counterintelligence secret – in a locked safe in his office. He chose to not inform President Truman, Attorney General J. Howard McGrath, or Secretaries of State Dean Acheson and General George Marshall while they held office. He informed the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) of the Venona Project in 1952.

In 1946 Attorney General Tom C. Clark authorized Hoover to compile a list of potentially disloyal Americans who might be detained during a wartime national emergency. In 1950, at the outbreak of the Korean War, Hoover submitted to President Truman a plan to suspend the writ of habeas corpus and detain 12,000 Americans suspected of disloyalty. Truman did not act on the plan.

COINTELPRO and the 1950s

In 1956, Hoover was becoming increasingly frustrated by U.S. Supreme Court decisions that limited the Justice Department's ability to prosecute people for their political opinions, most notably communists. Some of his aides reported that he purposely exaggerated the threat of communism to "ensure financial and public support for the FBI."

At this time he formalized a covert "dirty tricks" program under the name COINTELPRO. COINTELPRO was first used to disrupt the Communist Party USA, where Hoover went after targets that ranged from suspected everyday spies to larger celebrity figures such as Charlie Chaplin that he saw as spreading Communist Party propaganda.

In 1960s, Hoover's FBI monitored John Lennon and Malcolm X. The COINTELPRO tactics were later extended to organizations such as the Black Panther Party, Martin Luther King, Jr.'s Southern Christian Leadership Conference, and others. Hoover's moves against people who maintained contacts with subversive elements, some of whom were members of the civil rights movement, also led to accusations of trying to undermine their reputations.

Hoover amassed significant power by collecting files containing large amounts of compromising and potentially embarrassing information on many powerful people, especially politicians.

COINTELPRO's methods included infiltration, burglaries, illegal wiretaps, planting forged documents, and spreading false rumors about key members of target organizations. This program remained in place until it was exposed to the public in 1971, the committee declared COINTELPRO's activities were illegal and contrary to the Constitution.

Late career and death

Presidents Harry Truman and John F. Kennedy each considered dismissing Hoover as FBI Director, but ultimately concluded that the political cost of doing so would be too great.

Hoover personally directed the FBI investigation of the assassination of President John F. Kennedy. In 1964, just days before Hoover testified in the earliest stages of the Warren Commission hearings, President Lyndon B. Johnson waived the then-mandatory U.S. Government Service Retirement Age of 70, allowing Hoover to remain the FBI Director "for an indefinite period of time." The House Select Committee on Assassinations issued a report in 1979 critical of the performance by the FBI, the Warren Commission, and other agencies. The report criticized the FBI's (Hoover's) reluctance to thoroughly investigate the possibility of a conspiracy to assassinate the President.

When Richard Nixon took office in January 1969, Hoover had just turned 74. There was a growing sentiment in Washington, D.C., that the aging FBI chief needed to go, but Hoover's power and friends in Congress remained too strong for him to be forced into retirement.

Hoover remained director of the FBI until he died of a heart attack in his Washington home, on May 2, 1972. Hoover's body lay in state in the Rotunda of the U.S. Capitol, where Chief Justice Warren Burger eulogized him. President Richard Nixon delivered another eulogy at the funeral service in the National Presbyterian Church, and called Hoover one of the Giants, [whose] long life brimmed over with magnificent achievement and dedicated service to this country which he loved so well. Hoover was buried in the Congressional Cemetery in Washington, D.C., next to the graves of his parents and a sister who died in infancy.

Legacy

Biographer Kenneth D. Ackerman summarizes Hoover's legacy thus:

For better or worse, he built the FBI into a modern, national organization stressing professionalism and scientific crime-fighting. For most of his life, Americans considered him a hero. He made the G-Man brand so popular that, at its height, it was harder to become an FBI agent than to be accepted into an Ivy League college.

Hoover worked to groom the image of the FBI in American media; he was a consultant to Warner Brothers for a theatrical film about the FBI, The FBI Story (1959), and in 1965 on Warner's long-running spin-off television series, The F.B.I. Hoover personally made sure Warner portrayed the FBI more favorably than other crime dramas of the times.

Because Hoover's actions came to be seen as abuses of power, FBI directors are now limited to one 10 year term, subject to extension by the United States Senate.

The FBI Headquarters in Washington, DC is named the J. Edgar Hoover Building, after Hoover.

Hoover's practice of violating civil liberties for the sake of national security has been questioned in reference to recent national surveillance programs. An example is a lecture titled Civil Liberties and National Security: Did Hoover Get it Right?, given at The Institute of World Politics on April 21, 2015.

Honors

- 1938: Oklahoma Baptist University awarded Hoover an honorary doctorate during commencement exercises, at which he spoke.

- 1939: the National Academy of Sciences awarded Hoover its Public Welfare Medal.

- 1950: King George VI of the United Kingdom awarded Hoover an honorary knighthood in the Order of the British Empire.

- 1955: President Dwight Eisenhower gave Hoover the National Security Medal.

- 1966: President Lyndon B. Johnson bestowed the State Department's Distinguished Service Award on Hoover for his service as director of the FBI.

- 1973: The newly built FBI headquarters in Washington, D.C., is named the J. Edgar Hoover Building.

- 1974: Congress voted to honor Hoover's memory by publishing a memorial book, J. Edgar Hoover: Memorial Tributes in the Congress of the United States and Various Articles and Editorials Relating to His Life and Work.

- 1974: In Schaumburg, Illinois, a grade school was named after J. Edgar Hoover. However, in 1994, after information about Hoover's illegal activities was released, the school's name was changed to commemorate Herbert Hoover, instead.

Images for kids

-

Hoover investigated ex-Beatle John Lennon by putting the singer under surveillance, and Hoover wrote this letter to Richard Kleindienst, the US Attorney General in 1972. A 25-year battle by historian Jon Wiener under the Freedom of Information Act eventually resulted in the release of documents related to John Lennon, such as this one.

-

July 24, 1967. President Lyndon B. Johnson (seated, foreground) confers with (background L-R): Marvin Watson, J. Edgar Hoover, Sec. Robert McNamara, Gen. Harold Keith Johnson, Joe Califano, Sec. of the Army Stanley Rogers Resor, on responding to the Detroit riots

-

President Lyndon B. Johnson at the signing of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. White House East Room. People watching include Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, Senate Minority Leader Everett M. Dirksen, Senator Hubert Humphrey, First Lady "Lady Bird" Johnson, Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., F.B.I. Director J. Edgar Hoover, Speaker of the House John McCormack. Television cameras are broadcasting the ceremony.

-

Hoover and his assistant Clyde Tolson sitting in beach lounge chairs, c. 1939

See also

In Spanish: John Edgar Hoover para niños

In Spanish: John Edgar Hoover para niños