Jeremy Bentham facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Jeremy Bentham

|

|

|---|---|

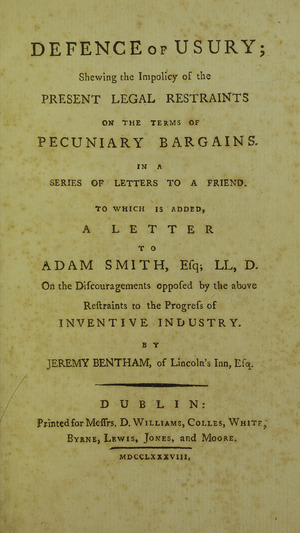

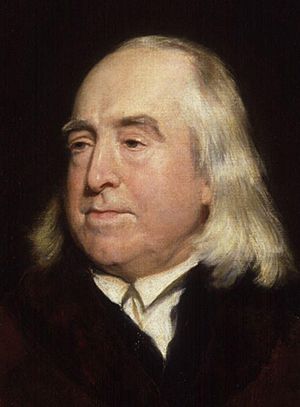

Portrait by Henry William Pickersgill

|

|

| Born | 15 February 1748 [O.S. 4 February 1747/8] |

| Died | 6 June 1832 (aged 84) London, England, United Kingdom

|

| Education | The Queen's College, Oxford (MA) |

| Era |

|

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Utilitarianism Legal positivism Liberalism Radicalism Epicureanism |

|

Main interests

|

Political philosophy, philosophy of law, ethics, economics |

|

Notable ideas

|

Principle of utility Felicific calculus |

|

Influenced

|

|

| Signature | |

|

|

Jeremy Bentham (/ˈbɛnθəm/; 4 February 1747/8 O.S. [15 February 1748 N.S.] – 6 June 1832) was an English philosopher, jurist, and social reformer regarded as the founder of modern utilitarianism.

Bentham defined as the "fundamental axiom" of his philosophy the principle that "it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong." He became a leading theorist in Anglo-American philosophy of law, and a political radical whose ideas influenced the development of welfarism. He advocated individual and economic freedoms, the separation of church and state, freedom of expression, equal rights for women, the right to divorce, and (in an unpublished essay) the decriminalising of homosexual acts. He called for the abolition of slavery, capital punishment and physical punishment, including that of children. He has also become known as an early advocate of animal rights. Though strongly in favour of the extension of individual legal rights, he opposed the idea of natural law and natural rights (both of which are considered "divine" or "God-given" in origin), calling them "nonsense upon stilts". Bentham was also a sharp critic of legal fictions.

Bentham's students included his secretary and collaborator James Mill, the latter's son, John Stuart Mill, the legal philosopher John Austin and American writer and activist John Neal. He "had considerable influence on the reform of prisons, schools, poor laws, law courts, and Parliament itself."

On his death in 1832, Bentham left instructions for his body to be first dissected, and then to be permanently preserved as an "auto-icon" (or self-image), which would be his memorial. This was done, and the auto-icon is now on public display in the entrance of the Student Centre at University College London (UCL). Because of his arguments in favour of the general availability of education, he has been described as the "spiritual founder" of UCL. However, he played only a limited direct part in its foundation.

Biography

Early life

Bentham was born on 4 February 1747/8 O.S. [15 February 1748 N.S.] in Houndsditch, London, to attorney Jeremiah Bentham (1712–1792) and Alicia Woodward (died 1759), widow of a Mr Whitehorne and daughter of mercer Thomas Grove, of Andover. His wealthy family were supporters of the Tory party. He was reportedly a child prodigy: he was found as a toddler sitting at his father's desk reading a multi-volume history of England, and he began to study Latin at the age of three. He learnt to play the violin, and at the age of seven Bentham would perform sonatas by Handel during dinner parties. He had one surviving sibling, Samuel Bentham (1757–1831), with whom he was close.

He attended Westminster School; in 1760, at age 12, his father sent him to The Queen's College, Oxford, where he completed his bachelor's degree in 1764, receiving the title of MA in 1767. He trained as a lawyer and, though he never practised, was called to the bar in 1769. He became deeply frustrated with the complexity of English law, which he termed the "Demon of Chicane". When the American colonies published their Declaration of Independence in July 1776, the British government did not issue any official response but instead secretly commissioned London lawyer and pamphleteer John Lind to publish a rebuttal. His 130-page tract was distributed in the colonies and contained an essay titled "Short Review of the Declaration" written by Bentham, a friend of Lind, which attacked and mocked the Americans' political philosophy.

Abortive prison project and the Panopticon

In 1786 and 1787, Bentham travelled to Krichev in White Russia (modern Belarus) to visit his brother, Samuel, who was engaged in managing various industrial and other projects for Prince Potemkin. It was Samuel (as Jeremy later repeatedly acknowledged) who conceived the basic idea of a circular building at the hub of a larger compound as a means of allowing a small number of managers to oversee the activities of a large and unskilled workforce.

Bentham began to develop this model, particularly as applicable to prisons, and outlined his ideas in a series of letters sent home to his father in England. He supplemented the supervisory principle with the idea of contract management; that is, an administration by contract as opposed to trust, where the director would have a pecuniary interest in lowering the average rate of mortality.

The Panopticon was intended to be cheaper than the prisons of his time, as it required fewer staff; "Allow me to construct a prison on this model", Bentham requested to a Committee for the Reform of Criminal Law, "I will be the gaoler. You will see ... that the gaoler will have no salary—will cost nothing to the nation." As the watchmen cannot be seen, they need not be on duty at all times, effectively leaving the watching to the watched. According to Bentham's design, the prisoners would also be used as menial labour, walking on wheels to spin looms or run a water wheel. This would decrease the cost of the prison and give a possible source of income.

The ultimately abortive proposal for a panopticon prison to be built in England was one among his many proposals for legal and social reform. But Bentham spent some sixteen years of his life developing and refining his ideas for the building and hoped that the government would adopt the plan for a National Penitentiary appointing him as contractor-governor. Although the prison was never built, the concept had an important influence on later generations of thinkers. Twentieth-century French philosopher Michel Foucault argued that the panopticon was paradigmatic of several 19th-century "disciplinary" institutions. Bentham remained bitter throughout his later life about the rejection of the panopticon scheme, convinced that it had been thwarted by the King and an aristocratic elite. Philip Schofield argues that it was largely because of his sense of injustice and frustration that he developed his ideas of "sinister interest"—that is, of the vested interests of the powerful conspiring against a wider public interest—which underpinned many of his broader arguments for reform.

On his return to England from Russia, Bentham had commissioned drawings from an architect, Willey Reveley. In 1791, he published the material he had written as a book, although he continued to refine his proposals for many years to come. He had by now decided that he wanted to see the prison built: when finished, it would be managed by himself as contractor-governor, with the assistance of Samuel. After unsuccessful attempts to interest the authorities in Ireland and revolutionary France, he started trying to persuade the prime minister, William Pitt, to revive an earlier abandoned scheme for a National Penitentiary in England, this time to be built as a panopticon. He was eventually successful in winning over Pitt and his advisors, and in 1794 was paid £2,000 for preliminary work on the project.

The intended site was one that had been authorised (under an act of 1779) for the earlier Penitentiary, at Battersea Rise; but the new proposals ran into technical legal problems and objections from the local landowner, Earl Spencer. Other sites were considered, including one at Hanging Wood, near Woolwich, but all proved unsatisfactory. Eventually Bentham turned to a site at Tothill Fields, near Westminster. Although this was common land, with no landowner, there were a number of parties with interests in it, including Earl Grosvenor, who owned a house on an adjacent site and objected to the idea of a prison overlooking it. Again, therefore, the scheme ground to a halt. At this point, however, it became clear that a nearby site at Millbank, adjoining the Thames, was available for sale, and this time things ran more smoothly. Using government money, Bentham bought the land on behalf of the Crown for £12,000 in November 1799.

From his point of view, the site was far from ideal, being marshy, unhealthy, and too small. When he asked the government for more land and more money, however, the response was that he should build only a small-scale experimental prison—which he interpreted as meaning that there was little real commitment to the concept of the panopticon as a cornerstone of penal reform. Negotiations continued, but in 1801 Pitt resigned from office, and in 1803 the new Addington administration decided not to proceed with the project. Bentham was devastated: "They have murdered my best days."

Nevertheless, a few years later the government revived the idea of a National Penitentiary, and in 1811 and 1812 returned specifically to the idea of a panopticon. Bentham, now aged 63, was still willing to be governor. However, as it became clear that there was still no real commitment to the proposal, he abandoned hope, and instead turned his attentions to extracting financial compensation for his years of fruitless effort. His initial claim was for the enormous sum of nearly £700,000, but he eventually settled for the more modest (but still considerable) sum of £23,000. An Act of Parliament in 1812 transferred his title in the site to the Crown.

More successful was his cooperation with Patrick Colquhoun in tackling the corruption in the Pool of London. This resulted in the Thames Police Bill of 1798, which was passed in 1800. The bill created the Thames River Police, which was the first preventive police force in the country and was a precedent for Robert Peel's reforms 30 years later.

Correspondence and contemporary influences

Bentham was in correspondence with many influential people. In the 1780s, for example, Bentham maintained a correspondence with the aging Adam Smith, in an unsuccessful attempt to convince Smith that interest rates should be allowed to freely float. As a result of his correspondence with Mirabeau and other leaders of the French Revolution, Bentham was declared an honorary citizen of France. He was an outspoken critic of the revolutionary discourse of natural rights and of the violence that arose after the Jacobins took power (1792). Between 1808 and 1810, he held a personal friendship with Latin American revolutionary Francisco de Miranda and paid visits to Miranda's Grafton Way house in London. He also developed links with José Cecilio del Valle.

In 1821, John Cartwright proposed to Bentham that they serve as "Guardians of Constitutional Reform", seven "wise men" whose reports and observations would "concern the entire Democracy or Commons of the United Kingdom". Describing himself, among the names mentioned which also included Sir Francis Burdett, George Ensor, and Sir Matthew Wood, and as a "nonentity", Bentham declined the offer.

South Australian colony proposal

On 3 August 1831 the Committee of the National Colonization Society approved the printing of its proposal to establish a free colony on the south coast of Australia, funded by the sale of appropriated colonial lands, overseen by a joint-stock company, and which would be granted powers of self-government as soon as was practicable. Contrary to assumptions, Bentham had no hand in the preparation of the 'Proposal to His Majesty's Government for founding a colony on the Southern Coast of Australia, which was prepared under the auspices of Robert Gouger, Charles Grey, 2nd Earl Grey, and Anthony Bacon. Bentham did, however, in August 1831, draft an unpublished work entitled 'Colonization Company Proposal', which constitutes his commentary upon the National Colonization Society's 'Proposal'.

Westminster Review

In 1823, he co-founded The Westminster Review with James Mill as a journal for the "Philosophical Radicals"—a group of younger disciples through whom Bentham exerted considerable influence in British public life. One was John Bowring, to whom Bentham became devoted, describing their relationship as "son and father": he appointed Bowring political editor of The Westminster Review and eventually his literary executor. Another was Edwin Chadwick, who wrote on hygiene, sanitation and policing and was a major contributor to the Poor Law Amendment Act: Bentham employed Chadwick as a secretary and bequeathed him a large legacy.

Personal life

Bentham never married.

An insight into his character is given in Michael St.

A psychobiographical study by Philip Lucas and Anne Sheeran argues that he may have had Asperger's syndrome. Bentham was an atheist.

Bentham's daily pattern was to rise at 6 am, walk for 2 hours or more, and then work until 4 pm.

Legacy

The Faculty of Laws at University College London occupies Bentham House, next to the main UCL campus.

Bentham's name was adopted by the Australian litigation funder IMF Limited to become Bentham IMF Limited on 28 November 2013, in recognition of Bentham being "among the first to support the utility of litigation funding".

Work

Utilitarianism

Bentham today is considered as the "Father of Utilitarianism". His ambition in life was to create a "Pannomion", a complete utilitarian code of law. He not only proposed many legal and social reforms, but also expounded an underlying moral principle on which they should be based. This philosophy of utilitarianism took for its "fundamental axiom" to be the notion that it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong. Bentham claimed to have borrowed this concept from the writings of Joseph Priestley, although the closest that Priestley in fact came to expressing it was in the form "the good and happiness of the members, that is the majority of the members of any state, is the great standard by which every thing [sic] relating to that state must finally be determined."

Bentham was a rare major figure in the history of philosophy to endorse psychological egoism. He was also a determined opponent of religion, as Crimmins observes: "Between 1809 and 1823 Jeremy Bentham carried out an exhaustive examination of religion with the declared aim of extirpating religious beliefs, even the idea of religion itself, from the minds of men."

Bentham also suggested a procedure for estimating the moral status of any action, which he called the hedonistic or felicific calculus.

Principle of utility

The principle of utility, or "greatest happiness principle", forms the cornerstone of all Bentham's thought. By "happiness", he understood a predominance of "pleasure" over "pain".

Bentham's Principles of Morals and Legislation focuses on the principle of utility and how this view of morality ties into legislative practices. His principle of utility regards good as that which produces the greatest amount of pleasure and the minimum amount of pain and evil as that which produces the most pain without the pleasure. This concept of pleasure and pain is defined by Bentham as physical as well as spiritual. Bentham writes about this principle as it manifests itself within the legislation of a society.

In order to measure the extent of pain or pleasure that a certain decision will create, he lays down a set of criteria divided into the categories of intensity, duration, certainty, proximity, productiveness, purity, and extent. Using these measurements, he reviews the concept of punishment and when it should be used as far as whether a punishment will create more pleasure or more pain for a society.

He calls for legislators to determine whether punishment creates an even more evil offence. Instead of suppressing the evil acts, Bentham argues that certain unnecessary laws and punishments could ultimately lead to new and more dangerous vices than those being punished to begin with, and calls upon legislators to measure the pleasures and pains associated with any legislation and to form laws in order to create the greatest good for the greatest number. He argues that the concept of the individual pursuing his or her own happiness cannot be necessarily declared "right", because often these individual pursuits can lead to greater pain and less pleasure for a society as a whole. Therefore, the legislation of a society is vital to maintain the maximum pleasure and the minimum degree of pain for the greatest number of people.

Hedonistic/felicific calculus

In his exposition of the felicific calculus, Bentham proposed a classification of 12 pains and 14 pleasures, by which we might test the "happiness factor" of any action. For Bentham, according to P. J. Kelly, the law "provides the basic framework of social interaction by delimiting spheres of personal inviolability within which individuals can form and pursue their own conceptions of well-being". It provides security, a precondition for the formation of expectations. As the hedonic calculus shows "expectation utilities" to be much higher than natural ones, it follows that Bentham does not favour the sacrifice of a few to the benefit of the many.

Criticisms

Utilitarianism was revised and expanded by Bentham's student John Stuart Mill, who sharply criticized Bentham's view of human nature, which failed to recognize conscience as a human motive. Mill considered Bentham's view "to have done and to be doing very serious evil." In Mill's hands, "Benthamism" became a major element in the liberal conception of state policy objectives.

Bentham's critics have claimed that he undermined the foundation of a free society by rejecting natural rights. Historian Gertrude Himmelfarb wrote "The principle of the greatest happiness of the greatest number was as inimical to the idea of liberty as to the idea of rights."

Bentham's "hedonistic" theory (a term from J. J. C. Smart) is often criticised for lacking a principle of fairness embodied in a conception of justice. In Bentham and the Common Law Tradition, Gerald J. Postema states: "No moral concept suffers more at Bentham's hand than the concept of justice. There is no sustained, mature analysis of the notion."

Economics

Bentham's opinions about monetary economics were completely different from those of David Ricardo; however, they had some similarities to those of Henry Thornton. He focused on monetary expansion as a means of helping to create full employment. He was also aware of the relevance of forced saving, propensity to consume, the saving-investment relationship, and other matters that form the content of modern income and employment analysis. His monetary view was close to the fundamental concepts employed in his model of utilitarian decision making. His work is considered to be an early precursor of modern welfare economics.

Bentham stated that pleasures and pains can be ranked according to their value or "dimension" such as intensity, duration, certainty of a pleasure or a pain. He was concerned with maxima and minima of pleasures and pains; and they set a precedent for the future employment of the maximisation principle in the economics of the consumer, the firm and the search for an optimum in welfare economics.

Bentham advocated "Pauper Management" which involved the creation of a chain of large workhouses.

Law reform

Bentham was the first person to be an aggressive advocate for the codification of all of the common law into a coherent set of statutes; he was actually the person who coined the verb "to codify" to refer to the process of drafting a legal code. He lobbied hard for the formation of codification commissions in both England and the United States, and went so far as to write to President James Madison in 1811 to volunteer to write a complete legal code for the young country. After he learned more about American law and realised that most of it was state-based, he promptly wrote to the governors of every single state with the same offer.

During his lifetime, Bentham's codification efforts were completely unsuccessful. Even today, they have been completely rejected by almost every common law jurisdiction, including England. However, his writings on the subject laid the foundation for the moderately successful codification work of David Dudley Field II in the United States a generation later.

Animal rights

Bentham is widely regarded as one of the earliest proponents of animal rights. He argued and believed that the ability to suffer, not the ability to reason, should be the benchmark, or what he called the "insuperable line". If reason alone were the criterion by which we judge who ought to have rights, human infants and adults with certain forms of disability might fall short, too. Earlier in the paragraph, Bentham makes clear that he accepted that animals could be killed for food, or in defence of human life, provided that the animal was not made to suffer unnecessarily. Bentham did not object to medical experiments on animals, providing that the experiments had in mind a particular goal of benefit to humanity, and had a reasonable chance of achieving that goal. He wrote that otherwise he had a "decided and insuperable objection" to causing pain to animals, in part because of the harmful effects such practices might have on human beings.

Imperialism

Bentham's writings in the early 1790s onwards expressed an opposition to imperialism. His 1793 pamphlet Emancipate Your Colonies! critiqued French colonialism. In the early 1820s, he argued that the liberal government in Spain should emancipate its New World colonies. In the essay Plan for an Universal and Perpetual Peace, Bentham argued that Britain should emancipate its New World colonies and abandon its colonial ambitions. He argued that empire was bad for the greatest number in the metropole and the colonies. According to Bentham, empire was financially unsound, entailed taxation on the poor in the metropole, caused unnecessary expansion in the military apparatus, undermined the security of the metropole, and were ultimately motivated by misguided ideas of honor and glory.

Privacy

For Bentham, transparency had moral value. For example, journalism puts power-holders under moral scrutiny. However, Bentham wanted such transparency to apply to everyone. This he describes by picturing the world as a gymnasium in which each "gesture, every turn of limb or feature, in those whose motions have a visible impact on the general happiness, will be noticed and marked down". He considered both surveillance and transparency to be useful ways of generating understanding and improvements for people's lives.

Fictional entities

Bentham distinguished among fictional entities what he called "fabulous entities" like Prince Hamlet or a centaur, from what he termed "fictitious entities", or necessary objects of discourse, similar to Kant's categories, such as nature, custom, or the social contract.

Death and the auto-icon

Bentham died on 6 June 1832, aged 84, at his residence in Queen Square Place in Westminster, London. He had continued to write up to a month before his death, and had made careful preparations for the preservation of his body as an auto-icon.

It is kept on public display at the main entrance of the UCL Student Centre. It was previously displayed at the end of the South Cloisters in the main building of the college until it was moved in 2020.

University College London

Bentham is widely associated with the foundation in 1826 of London University (the institution that, in 1836, became University College London), though he was 78 years old when the university opened and played only an indirect role in its establishment. His direct involvement was limited to his buying a single £100 share in the new university, making him just one of over a thousand shareholders.

Bentham and his ideas can nonetheless be seen as having inspired several of the actual founders of the university. He strongly believed that education should be more widely available, particularly to those who were not wealthy or who did not belong to the established church; in Bentham's time, membership of the Church of England and the capacity to bear considerable expenses were required of students entering the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge. As the University of London was the first in England to admit all, regardless of race, creed or political belief, it was largely consistent with Bentham's vision. There is some evidence that, from the sidelines, he played a "more than passive part" in the planning discussions for the new institution, although it is also apparent that "his interest was greater than his influence". He failed in his efforts to see his disciple John Bowring appointed professor of English or History, but he did oversee the appointment of another pupil, John Austin, as the first professor of Jurisprudence in 1829.

The more direct associations between Bentham and UCL—the college's custody of his Auto-icon (see above) and of the majority of his surviving papers—postdate his death by some years: the papers were donated in 1849, and the Auto-icon in 1850. A large painting by Henry Tonks hanging in UCL's Flaxman Gallery depicts Bentham approving the plans of the new university, but it was executed in 1922 and the scene is entirely imaginary. Since 1959 (when the Bentham Committee was first established), UCL has hosted the Bentham Project, which is progressively publishing a definitive edition of Bentham's writings.

UCL now endeavours to acknowledge Bentham's influence on its foundation, while avoiding any suggestion of direct involvement, by describing him as its "spiritual founder".

See also

In Spanish: Jeremy Bentham para niños

In Spanish: Jeremy Bentham para niños

- List of animal rights advocates

- List of civil rights leaders

- List of liberal theorists

- Philosophy of happiness

- Rule according to higher law

- Rule of law