Juana Inés de la Cruz facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Juana Inés de la Cruz

O.S.H.

|

|

|---|---|

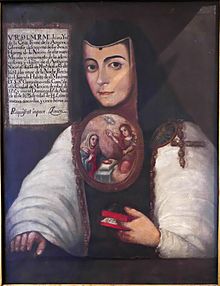

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz by Miguel Cabrera

|

|

| Native name |

Doña Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana

|

| Born | Juana Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana 12 November 1648 San Miguel Nepantla, New Spain (near modern Tepetlixpa, Mexico) |

| Died | 17 April 1695 (aged 46) Mexico City, New Spain |

| Resting place | Convent of San Jerónimo, Mexico City |

| Pen name | Juana Inés de la Cruz |

| Occupation | Nun, poet, writer, musician composer |

| Language | Spanish, Nahuatl, Latin |

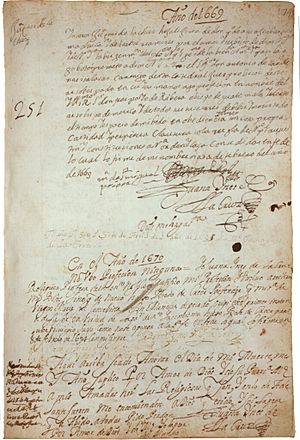

| Education | Self taught until the age of twenty-one. (1669) |

| Period | 17th century Nun |

| Literary movement | Baroque |

| Years active | ~1660 to ~1693 |

|

|

|

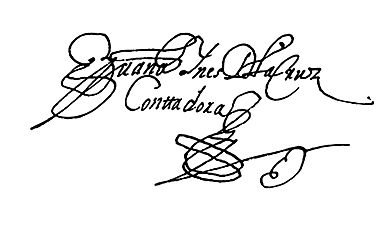

| Signature |  |

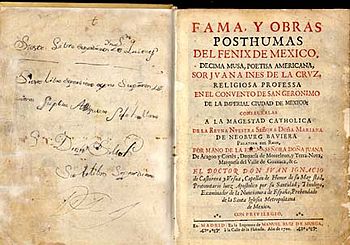

Doña Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana, better known as Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz OSH (12 November 1648 – 17 April 1695) was a Mexican writer, philosopher, composer and poet of the Baroque period, and Hieronymite nun. Her contributions to the Spanish Golden Age gained her the nicknames of "The Tenth Muse" or "The Phoenix of America"; historian Stuart Murray calls her a flame that rose from the ashes of "religious authoritarianism".

Sor Juana lived during Mexico's colonial period, making her a contributor both to early Spanish literature as well as to the broader literature of the Spanish Golden Age. Beginning her studies at a young age, Sor Juana was fluent in Latin and also wrote in Nahuatl, and became known for her philosophy in her teens. Sor Juana educated herself in her own library, which was mostly inherited from her grandfather. After joining a nunnery in 1667, Sor Juana began writing poetry and prose dealing with such topics as love, environmentalism, feminism, and religion. She turned her nun's quarters into a salon, visited by New Spain's female intellectual elite, including Doña Eleonora del Carreto, Marchioness of Mancera, and Doña Maria Luisa Gonzaga, Countess of Paredes de Nava, both Vicereines of the New Spain, amongst others. Her criticism of misogyny and the hypocrisy of men led to her condemnation by the Bishop of Puebla, and in 1694 she was forced to sell her collection of books and focus on charity towards the poor. She died the next year, having caught the plague while treating her sisters.

After she had faded from academic discourse for hundreds of years, Nobel Prize winner Octavio Paz re-established Sor Juana's importance in modern times. Scholars now interpret Sor Juana as a protofeminist, and she is the subject of vibrant discourse about themes such as colonialism, education rights, women's religious authority, and writing as examples of feminist advocacy.

Contents

Life

Early life

Doña Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana was born in San Miguel Nepantla (now called Nepantla de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz) near Mexico City. Owing to her Spanish ancestry and Mexican birth, Inés is considered a Criolla. She was the illegitimate child of Don Pedro Manuel de Asuaje y Vargas-Machuca, a Spanish officer, and Doña Isabel Ramírez de Santillana y Rendón, a wealthy criolla, who inhabited the Hacienda of Panoaya, close to Mexico City. She was baptized on 2 December 1651 with the name of “Inés” ("Juana" was only added after she entered the convent) described on the baptismal rolls as "a daughter of the Church". The name “Inés” came from her maternal aunt “Doña” Inés Ramírez de Santillana, who received the name herself from her Andalusian grandmother “Doña” Inés de Brenes. The name “Inés” was also present through their cousin Doña Inés de Brenes y Mendoza, married to a grandson of Antonio de Saavedra Guzmán, the first ever published American-born poet.

Her biological father, according to all accounts, was completely absent from her life. However, thanks to her maternal grandfather, who owned a very productive hacienda in Amecameca, Inés lived a comfortable life with her mother on his estate, Panoaya, accompanied by an illustrious group of relatives who constantly visited or were visited in their surrounding haciendas.

During her childhood, Inés often hid in the hacienda chapel to read her grandfather's books from the adjoining library, something forbidden to girls. By the age of three, she had learned how to read and write Latin. By the age of five, she reportedly could do accounts. At age eight, she composed a poem on the Eucharist. By adolescence, Inés had mastered Greek logic, and at age thirteen she was teaching Latin to young children. She also learned the Aztec language of Nahuatl and wrote some short poems in that language.

In 1664, at the age of 16, Inés was sent to live in Mexico City. She even asked her mother's permission to disguise herself as a male student so that she could enter the university there, without success. Without the ability to obtain formal education, Juana continued her studies privately. Her family's influential position had gained her the position of lady-in-waiting at the colonial viceroy's court, where she came under the tutelage of the Vicereine Donna Eleonora del Carretto, member of one of Italy's most illustrious families, and wife of the Viceroy of New Spain Don Antonio Sebastián de Toledo, Marquis of Mancera. The viceroy Marquis de Mancera, wishing to test the learning and intelligence of the 17-year-old, invited several theologians, jurists, philosophers, and poets to a meeting, during which she had to answer many questions unprepared and explain several difficult points on various scientific and literary subjects. The manner in which she acquitted herself astonished all present and greatly increased her reputation. Her literary accomplishments garnered her fame throughout New Spain. She was much admired in the viceregal court, and she received several proposals of marriage, which she declined.

Religious life and name change

In 1667, she entered the Monastery of St. Joseph, a community of the Discalced Carmelite nuns, as a postulant, where she remained but a few months. Later, in 1669, she entered the monastery of the Hieronymite nuns, which had more relaxed rules, where she changed her name to Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, probably in reference to Sor Juana de la Cruz Vázquez Gutiérrez who was a Spanish nun whose erudition earned her one of the few dispensations for women to preach the gospel. Another potential namesake was Saint Juan de la Cruz, one of the most accomplished authors of the Spanish Baroque. She chose to become a nun so that she could study as she wished since she wanted "to have no fixed occupation which might curtail my freedom to study."

In the convent and perhaps earlier, Sor Juana became intimate friends with fellow savant, Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora, who visited her in the convent's locutorio. She stayed cloistered in the Convent of Santa Paula of the Hieronymite in Mexico City from 1669 until her death in 1695, and there she studied, wrote, and collected a large library of books. The Viceroy and Vicereine of New Spain became her patrons; they supported her and had her writings published in Spain. She addressed some of her poems to paintings of her friend and patron María Luisa Manrique de Lara y Gonzaga, daughter of Vespasiano Gonzaga, Duca di Guastala, Luzara e Rechiolo and Inés María Manrique, 9th Countess de Paredes, which she also addressed as Lísida.

In November 1690, the bishop of Puebla, Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz published, under the pseudonym of Sor Filotea, and without her permission, Sor Juana's critique of a 40-year-old sermon by Father António Vieira, a Portuguese Jesuit preacher. Although Sor Juana's intentions for the work, called Carta Atenagórica are left to interpretation, many scholars have opted to interpret the work as a challenge to the hierarchical structure of religious authority. Along with Carta Atenagórica, the bishop also published his own letter in which he said she should focus on religious instead of secular studies. He published his criticisms to use them to his advantage against the priest, and while he agreed with her criticisms, he believed that as a woman, she should devote herself to prayer and give up her writings.

In response to her critics, Sor Juana wrote a letter, Respuesta a Sor Filotea de la Cruz (Reply to Sister Philotea), in which she defended women's right to formal education. She also advocated for women's right to serve as intellectual authorities, not only through the act of writing, but also through the publication of their writing. By putting women, specifically older women, in positions of authority, Sor Juana argued, women could educate other women. Resultingly, Sor Juana argued, this practice could also avoid potentially dangerous situations involving male teachers in intimate settings with young female students. In 1691, she was reprimanded and ordered to stop writing after the exposure of a private letter in which she wrote of the right of women to education.

In addition to her status as a woman in a self-prescribed position of authority, Sor Juana's radical position made her an increasingly controversial figure. She famously remarked by quoting an Aragonese poet and echoing St. Teresa of Ávila: "One can perfectly well philosophize while cooking supper." In response, Francisco de Aguiar y Seijas, Archbishop of Mexico joined other high-ranking officials in condemning Sor Juana's "waywardness." In addition to opposition she received for challenging the patriarchal structure of the Catholic Church, Sor Juana was repeatedly criticized for believing that her writing could achieve the same philanthropic goals as community work.

By 1693, she seemingly ceased to write, rather than risking official censure. Although there is no undisputed evidence of her renouncing devotion to letters, there are documents showing her agreeing to undergo penance. Her name is affixed to such a document in 1694, but given her deep natural lyricism, the tone of the supposed handwritten penitentials is in rhetorical and autocratic Church formulae; one is signed "Yo, la Peor de Todas" ("I, the worst of all women"). She is said to have sold all her books, then an extensive library of over 4,000 volumes, and her musical and scientific instruments as well. Other sources report that her defiance toward the Church led to the confiscation of all of her books and instruments, although the bishop himself agreed with the contents of her letters.

Of over one hundred unpublished works, only a few of her writings have survived, which are known as the Complete Works. According to Octavio Paz, her writings were saved by the vicereine.

She died after ministering to other nuns stricken during a plague, on 17 April 1695. Sigüenza y Góngora delivered the eulogy at her funeral.

Works

Poetry

First Dream

First Dream, a long philosophical and descriptive silva (a poetic form combining verses of 7 and 11 syllables), "deals with the shadow of night beneath which a person falls asleep in the midst of quietness and silence, where night and day animals participate, either dozing or sleeping, all urged to silence and rest by Harpocrates. The person's body ceases its ordinary operations, which are described in physiological and symbolical terms, ending with the activity of the imagination as an image-reflecting apparatus: the Pharos. From this moment, her soul, in a dream, sees itself free at the summit of her own intellect; in other words, at the apex of an own pyramid-like mount, which aims at God and is luminous.

There, perched like an eagle, she contemplates the whole creation, but fails to comprehend such a sight in a single concept. Dazzled, the soul's intellect faces its own shipwreck, caused mainly by trying to understand the overwhelming abundance of the universe, until reason undertakes that enterprise, beginning with each individual creation, and processing them one by one, helped by the Aristotelic method of ten categories.

The soul cannot get beyond questioning herself about the traits and causes of a fountain and a flower, intimating perhaps that his method constitutes a useless effort, since it must take into account all the details, accidents, and mysteries of each being. By that time, the body has consumed all its nourishment, and it starts to move and wake up, soul and body are reunited. The poem ends with the Sun overcoming Night in a straightforward battle between luminous and dark armies, and with the poet's awakening.

Love poetry

Sor Juana's first volume of poetry, Inundación castálida, was published in Spain by the Vicereine Maria Luisa Manrique de Lara y Gonzága, Countess of Paredes, Marquise de la Laguna. Many of her poems dealt with the subject of love and sensuality. One of Sor Juana's sonnets:

| Soneto 173 | Sonnet 173 in Edith Grossman's 2014 translation |

|---|---|

|

Efectos muy penosos de amor, y que no por grandes se igualan con las prendas de quien le causa

¿Vesme, Alcino, que atada a la cadena |

The very distressing effects of love, but no matter how great, they do not equal the qualities of the one who causes them

Do you see me, Alcino, here am I caught |

Dramas

In addition to the two comedies outlined here (House of Desires [Los empeños de una casa]) and Love is but a Labyrinth [Amor es mas laberinto]), Sor Juana is attributed as the author of a possible ending to the comedy by Agustin de Salazar: The Second Celestina (La Segunda Celestina). In the 1990s, Guillermo Schmidhuber found a release of the comedy that contained a different ending than the otherwise known ending. He proposed that those one thousand words were written by Sor Juana. Some literary critics, such as Octavio Paz, Georgina Sabat-Rivers, and Luis Leal) have accepted Sor Juana as the co-author, but others, such as Antonio Alatorre and José Pascual Buxó, have refuted it.

Comedies

Scholars have debated the meaning of Juana's comedies. Julie Greer Johnson describes how Juana protested against the rigorously defined relationship between genders through her full-length comedies and humor. She argues that Juana recognized the negative view of women in comedy which was designed to uphold male superiority at the expense of women. By recognizing the power of laughter, Juana appropriated the purpose of humor, and used it as a socially acceptable medium with which to question notions of men and women.

Pawns of a House

The work was first performed on October 4, 1683, during the celebration of the Viceroy Count of Paredes’ first son's birth. Some critics maintain that it could have been set up for the Archbishop Francisco de Aguiar y Seijas’ entrance to the capital, but this theory is not considered reliable.

The story revolves around two couples who are in love but, by chance of fate, cannot yet be together. This comedy of errors is considered one of the most prominent works of late baroque Spanish-American literature. One of its most peculiar characteristics is that the driving force in the story is a woman with a strong, decided personality who expresses her desires to a nun. The protagonist of the story, Dona Leonor, fits the archetype perfectly.

It is often considered the peak of Sor Juana's work and even the peak of all New-Hispanic literature. Pawns of a House is considered a rare work in colonial Spanish-American theater due to the management of intrigue, representation of the complicated system of marital relationships, and the changes in urban life.

Love is but a Labyrinth

The work premiered on February 11, 1689, during the celebration of the inauguration of the viceroyalty Gaspar de la Cerda y Mendoza. However, in his Essay on Psychology, Ezequiel A. Chavez mentions Fernandez del Castillo as a coauthor of this comedy.

The plot takes on the well-known theme in Greek mythology of Theseus: a hero from Crete Island. He fights against the Minotaur and awakens the love of Ariadne and Phaedra. Sor Juana conceived Theseus as the archetype of the baroque hero, a model also used by her fellow countryman Juan Ruiz de Alarcón. Theseus’ triumph over the Minotaur does not make Theseus proud, but instead allows him to be humble.

Music

Besides poetry and philosophy, Sor Juana was interested in science, mathematics and music. The latter represents an important aspect, not only because musicality was an intrinsic part of the poetry of the time but also for the fact that she devoted a significant portion of her studies to the theory of instrumental tuning that, especially in the Baroque period, had reached a point of critical importance. So involved was Sor Juana in the study of music, that she wrote a treatise called El Caracol (which is lost now) that sought to simplify musical notation and solve the problems that Pythagorean tuning suffered.

In the writings of Juana Inés, it is possible to detect the importance of sound. We can observe this in two ways. First of all, the analysis of music and the study of musical temperament appears in several of her poems. For instance, in the following poem, Sor Juana delves into the natural notes and the accidentals of musical notation:

Professor Sarah Finley argues that the visual is related with patriarchal themes, while the sonorous offers an alternative to the feminine space in the work of Sor Juana. As an example of this, Finley points out that Narciso falls in love with a voice, and not with a reflection.

Other notable works

One musical work attributed to Sor Juana survives from the archive of Guatemala Cathedral. This is a 4-part villancico, Madre, la de los primores.

Other works include Hombres Necios (Foolish Men), and The Divine Narcissus.

Historical influence

Philanthropy

The Sor Juana Inés Services for Abused Women was established in 1993 to pay Sor Juana's dedication to helping women survivors of domestic violence forward. Renamed the Community Overcoming Relationship Abuse (CORA), the organization offers community, legal, and family support services in Spanish to Latin American women and children who have faced or are facing domestic violence.

Education

The San Jerónimo Convent, where Juana lived the last 27 years of her life and where she wrote most of her work is today the University of the Cloister of Sor Juana in the historic center of Mexico City. The Mexican government founded in the university in 1979.

Contribution to feminism

Historic feminist movements

Amanda Powell locates Sor Juana as a contributor to the Querelles des Femmes, a three-century long literary debate about women. Central to this early feminist debate were ideas about gender and sex, and, consequently, misogyny.

Powell argues that the formal and informal networks and pro-feminist ideas of the Querelles des Femmes were important influences on Sor Juana's work, La Respuesta. For women, Powell argues, engaging in conversation with other women was as significant as communicating through writing. However, while Teresa of Ávila appears in Sor Juana's La Respuesta, Sor Juana makes no mention of the person who launched the debate, Christine de Pizan. Rather than focusing on Sor Juana's engagement with other literary works, Powell prioritizes Sor Juana's position of authority in her own literary discourse. This authoritative stance not only demonstrates a direct counter to misogyny, but was also typically reserved for men. As well, Sor Juana's argument that ideas about women in religious hierarchies are culturally constructed, not divine, echoes ideas about the construction of gender and sex.

Modern feminist movements

Yugar connects Sor Juana to feminist advocacy movements in the twenty-first century, such as religious feminism, ecofeminism, and the feminist movement in general.

Although the current religious feminist movement grew out of the Liberation Theology movement of the 1970s, Yugar uses Sor Juana's criticism of religious law that permits only men to occupy leadership positions within the Church as early evidence of her religious feminism. Based on Sor Juana's critique of the oppressive and patriarchal structures of the Church of her day, Yugar argues that Sor Juana predated current movements, like Latina Feminist Theology, that privilege Latina women's views on religion. She also cites modern movements such as the Roman Catholic Women Priest Movement, the Women's Ordination Conference, and the Women's Alliance for Theology, Ethics and Ritual, all of which also speak out against the patriarchal limitations on women in religious institutions.

Yugar emphasizes that Sor Juana interpreted the Bible as expressing concern with people of all backgrounds as well as with the earth. Most significantly, Yugar argues, Sor Juana expressed concern over the consequences of capitalistic Spanish domination over the earth. These ideas, Yugar points out, are commonly associated with modern feminist movements concerned with decolonization and the protection of the planet.

Alicia Gaspar de Alba connects Sor Juana to the modern lesbian movement and Chicana movement. She links Sor Juana to criticizing the concepts of compulsory heterosexuality and advocating the idea of a lesbian continuum, both of which are credited to well-known feminist writer and advocate Adrienne Rich. As well, Gaspar de Alba locates Sor Juana in the Chicana movement, which has not been accepting of "Indigenous lesbians".

A symbol

Colonial and indigenous identities

As a woman in religion, Sor Juana has become associated with the Virgin of Guadalupe, a religious symbol of Mexican identity, but was also connected to Aztec goddesses. For example, parts of Sor Juana's Villancico 224 are written in Nahuatl, while others are written in Spanish. The Virgin of Guadalupe is the subject of the Villancico, but depending on the language, the poem refers to both the Virgin of Guadalupe and Cihuacoatl, an Indigneous goddess. It is ambiguous whether Sor Juana prioritizes the Mexican or indigenous religious figure, or whether her focus is on harmonizing the two.

Sor Juana's connection to indigenous religious figures is also prominent in her Loa to Divine Narcissus, (Spanish "El Divino Narciso") (see Jauregui 2003, 2009). The play centers on the interaction between two Indigenous people, named Occident and America, and two Spanish people, named Religion and Zeal. The characters exchange their religious perspectives, and conclude that there are more similarities between their religious traditions than there are differences. The loa references Aztec rituals and gods, including Huitzilopochtli, who symbolized the land of Mexico.

Scholars like Nicole Gomez argue that Sor Juana's fusion of Spanish and Aztec religious traditions in her Loa to Divine Narcissus aims to raise the status of indigenous religious traditions to that of Catholicism in New Spain. Gomez argues that Sor Juana also emphasizes the violence with which Spanish religious traditions dominated indigenous ones. Ultimately, Gomez argues that Sor Juana's use of both colonial and indigenous languages, symbols, and religious traditions not only gives voice to indigenous peoples, who were marginalized, but also affirms her own indigenous identity.

Through their scholarly interpretations of Sor Juana's work, Octavio Paz and Alicia Gaspar de Alba have also incorporated Sor Juana into discourses about Mexican identity. Paz's accredited scholarship on Sor Juana elevated her to a national symbol as a Mexican woman, writer, and religious authority. On the contrary, Gaspar de Alba emphasized Sor Juana's indigenous identity by inserting her into Chicana discourses.

Connection to Frida Kahlo

Paul Allatson emphasizes that women like Sor Juana and Frida Kahlo masculinized their appearances to symbolically complicate the space marked for women in society. Sor Juana's decision to cut her hair as punishment for mistakes she made during learning signified her own autonomy, but was also a way to engage in the masculinity expected of male-dominated spaces, like universities. According to Paul Allatson, nuns were also required to cut their hair after entering the convent. These ideas, Allatson suggests, are echoed in Frida Kahlo's 1940 self-portrait titled Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair, or Autorretrato con cabellos corto.

As well, the University of the Cloister of Sor Juana honored both Frida Kahlo and Sor Juana on October 31, 2018, with a symbolic altar. The altar, called Las Dos Juanas, was specially made for the Day of the Dead.

Official recognition by the Mexican government

In present times, Sor Juana is still an important figure in Mexico.

In 1995, Sor Juana's name was inscribed in gold on the wall of honor in the Mexican Congress in April 1995. In addition, Sor Juana is pictured on the obverse of the 200 pesos bill issued by the Banco de Mexico, and the 1000 pesos coin minted by Mexico between 1988 and 1992. The town where Sor Juana grew up, San Miguel Nepantla in the municipality of Tepetlixpa, State of Mexico, was renamed in her honor as Nepantla de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.

Veneration

In 2022, the Episcopal Church of the United States gave final approval and added her feast to the liturgical calendar. Her feast day is April 18.

Popular culture

Literature

- American poet Diane Ackerman wrote a verse drama, Reverse Thunder, about Sor Juana (1992).

- Canadian poet and novelist Margaret Atwood's 2007 book of poems The Door includes a poem entitled "Sor Juana Works in the Garden".

- Puerto Rican poet Giannina Braschi wrote the postmodern Spanglish novel Yo-Yo Boing! in which characters debate the greatest women poets, acknowledging both Sor Juana and Emily Dickinson.

- Canadian novelist Paul Anderson devoted 12 years writing a 1300-page novel entitled Hunger's Brides (pub. 2004) on Sor Juana. His novel won the 2005 Alberta Book Award.

Music

- American composer John Adams and director Peter Sellars used two of Sor Juana's poems, Pues mi Dios ha nacido a penar and Pues está tiritando in their libretto for the Nativity oratorio-opera El Niño (2000).

- Composer Allison Sniffin's original composition, Óyeme con los ojos – (Hear Me with Your Eyes: Sor Juana on the Nature of Love), based on text and poetry by Sor Juana, was commissioned by Melodia Women's Choir, which premiered the work at the Kaufman Center in New York City.

- Composer Daniel Crozier and librettist Peter M. Krask wrote With Blood, With Ink, an opera based around her life, while both were students at Baltimore's Peabody Institute in 1993. The work won first prize in the National Operatic and Dramatic Association's Chamber Opera Competition. In 2000, excerpts were included in the New York City Opera's Showcasing American Composers Series. The work in its entirety was premiered by the Fort Worth Opera on April 20, 2014, and recorded by Albany Records.

- Puerto Rican singer iLe recites part of one of Sor Juana's sonnets in her song "Rescatarme".

- In 2013, the Brazilian composer Jorge Antunes composed an electroacoustic musical work entitled CARTA ATHENAGÓRICA, in the studio of CMMAS (Mexican Center for Music and Sound Arts) in the city of Morelia, with the support of Ibermúsicas. The composition, which honors Sor Juana is called "Figurative Music", in which the musical structure and musical objects are based on rhetoric with figures of speech. In the work Antunes uses the chiasmus, also called retruécano, from poems of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.

Film, television and video

- A telenovela about her life, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, was created in 1962.

- María Luisa Bemberg wrote and directed the 1990 film Yo, la peor de todas (I, the Worst of All), based on Octavo Paz's Sor Juana: Or, the Traps of Faith based on Sor Juana's life.

- The Spanish-language miniseries Juana Inés (2016) by Canal Once TV, starring Arantza Ruiz and Arcelia Ramírez as Sor Juana, dramatizes her life.

Theater

- Helen Edmundson's play The Heresy of Love, based on the life of Sor Juana, was premiered by the Royal Shakespeare Company in early 2012 and revived by Shakespeare's Globe in 2015.

- Jesusa Rodríguez has produced a number of works concerning Sor Juana.

- Playwright, director, and producer Kenneth Prestininzi wrote Impure Thoughts (Without Apology) which follows Sor Juana's experience with Bishop Francisco Aguilar y Seijas. "[1]".

- Tanya Saracho's play The Tenth Muse, a fictionalized 18th century drama about women in a convent in Colonial Mexico included seven female characters and their discovery of and relationship to Sor Juana's writings, debuted at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival.

See also

In Spanish: Juana Inés de la Cruz para niños

In Spanish: Juana Inés de la Cruz para niños