Louis de Broglie facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Louis de Broglie

|

|

|---|---|

Broglie in 1929

|

|

| Born | 15 August 1892 Dieppe, France

|

| Died | 19 March 1987 (aged 94) Louveciennes, France

|

| Alma mater | University of Paris (ΒΑ in History, 1910; BA in Sciences, 1913; PhD in physics, 1924) |

| Known for | Wave nature of electrons De Broglie–Bohm theory De Broglie waves |

| Awards | Nobel Prize in Physics (1929) Henri Poincaré Medal (1929) Albert I of Monaco Prize (1932) Max Planck Medal (1938) Kalinga Prize (1952) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Physics |

| Institutions | University of Paris (Sorbonne) |

| Thesis | Recherches sur la théorie des quanta ("Research on Quantum Theory") (1924) |

| Doctoral advisor | Paul Langevin |

| Doctoral students | Cécile DeWitt-Morette Bernard d'Espagnat Jean-Pierre Vigier Alexandru Proca Marie-Antoinette Tonnelat |

Louis Victor Pierre Raymond, 7th Duc de Broglie (/də ˈbroʊɡli/, also US: /də broʊˈɡliː, də ˈbrɔɪ/, French: [də bʁɔj] or [də bʁœj] ; 15 August 1892 – 19 March 1987) was a French physicist and aristocrat who made groundbreaking contributions to quantum theory. In his 1924 PhD thesis, he postulated the wave nature of electrons and suggested that all matter has wave properties. This concept is known as the de Broglie hypothesis, an example of wave–particle duality, and forms a central part of the theory of quantum mechanics.

De Broglie won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1929, after the wave-like behaviour of matter was first experimentally demonstrated in 1927.

The 1925 pilot-wave model, and the wave-like behaviour of particles discovered by de Broglie was used by Erwin Schrödinger in his formulation of wave mechanics. The pilot-wave model and interpretation was then abandoned, in favor of the quantum formalism, until 1952 when it was rediscovered and enhanced by David Bohm.

Louis de Broglie was the sixteenth member elected to occupy seat 1 of the Académie française in 1944, and served as Perpetual Secretary of the French Academy of Sciences. De Broglie became the first high-level scientist to call for establishment of a multi-national laboratory, a proposal that led to the establishment of the European Organization for Nuclear Research (CERN).

Biography

Origin and education

Louis de Broglie belonged to the famous aristocratic family of Broglie, whose representatives for several centuries occupied important military and political posts in France. The father of the future physicist, Louis-Alphonse-Victor, 5th duc de Broglie, was married to Pauline d’Armaille, the granddaughter of the Napoleonic General Philippe Paul, comte de Ségur and his wife, the biographer, Marie Célestine Amélie d'Armaillé. They had five children; in addition to Louis, these were: Albertina (1872–1946), subsequently the Marquise de Luppé; Maurice (1875–1960), subsequently a famous experimental physicist; Philip (1881–1890), who died two years before the birth of Louis, and Pauline, Comtesse de Pange (1888–1972), subsequently a famous writer. Louis was born in Dieppe, Seine-Maritime. As the youngest child in the family, Louis grew up in relative loneliness, read a lot, and was fond of history, especially political. From early childhood, he had a good memory and could accurately read an excerpt from a theatrical production or give a complete list of ministers of the Third Republic of France. For him it was predicted a great future as a statesman.

De Broglie had intended a career in humanities, and received his first degree in history. Afterwards he turned his attention toward mathematics and physics and received a degree in physics. With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, he offered his services to the army in the development of radio communications.

Military service

After graduation, Louis de Broglie as a simple sapper joined the engineering forces to undergo compulsory service. It began at Fort Mont Valérien, but soon, on the initiative of his brother, he was seconded to the Wireless Communications Service and worked on the Eiffel Tower, where the radio transmitter was located. Louis de Broglie remained in military service throughout the First World War, dealing with purely technical issues. In particular, together with Léon Brillouin and brother Maurice, he participated in establishing wireless communications with submarines. Prince Louis was demobilized in August 1919 with the rank of adjudant. Later, the scientist regretted that he had to spend about six years away from the fundamental problems of science that interested him.

Scientific and pedagogical career

His 1924 thesis Recherches sur la théorie des quanta (Research on the Theory of the Quanta) introduced his theory of electron waves. This included the wave–particle duality theory of matter, based on the work of Max Planck and Albert Einstein on light. This research culminated in the de Broglie hypothesis stating that any moving particle or object had an associated wave. De Broglie thus created a new field in physics, the mécanique ondulatoire, or wave mechanics, uniting the physics of energy (wave) and matter (particle). For this he won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1929.

In his later career, de Broglie worked to develop a causal explanation of wave mechanics, in opposition to the wholly probabilistic models which dominate quantum mechanical theory; it was refined by David Bohm in the 1950s. The theory has since been known as the De Broglie–Bohm theory.

In addition to strictly scientific work, de Broglie thought and wrote about the philosophy of science, including the value of modern scientific discoveries. In 1930 he founded the book series Actualités scientifiques et industrielles published by Éditions Hermann.

De Broglie became a member of the Académie des sciences in 1933, and was the academy's perpetual secretary from 1942. He was asked to join Le Conseil de l'Union Catholique des Scientifiques Francais, but declined because he was non-religious. On 12 October 1944, he was elected to the Académie Française, replacing mathematician Émile Picard. Because of the deaths and imprisonments of Académie members during the occupation and other effects of the war, the Académie was unable to meet the quorum of twenty members for his election; due to the exceptional circumstances, however, his unanimous election by the seventeen members present was accepted. In an event unique in the history of the Académie, he was received as a member by his own brother Maurice, who had been elected in 1934. UNESCO awarded him the first Kalinga Prize in 1952 for his work in popularizing scientific knowledge, and he was elected a Foreign Member of the Royal Society on 23 April 1953.

Louis became the 7th duc de Broglie in 1960 upon the death without heir of his elder brother, Maurice, 6th duc de Broglie, also a physicist.

In 1961, he received the title of Knight of the Grand Cross in the Légion d'honneur. De Broglie was awarded a post as counselor to the French High Commission of Atomic Energy in 1945 for his efforts to bring industry and science closer together. He established a center for applied mechanics at the Henri Poincaré Institute, where research into optics, cybernetics, and atomic energy were carried out. He inspired the formation of the International Academy of Quantum Molecular Science and was an early member.

Louis never married. When he died on 19 March 1987 in Louveciennes at the age of 94, he was succeeded as duke by a distant cousin, Victor-François, 8th duc de Broglie. His funeral was held 23 March 1987 at the Church of Saint-Pierre-de-Neuilly.

Scientific activity

Physics of X-ray and photoelectric effect

The first works of Louis de Broglie (early 1920s) were performed in the laboratory of his older brother Maurice and dealt with the features of the photoelectric effect and the properties of x-rays. These publications examined the absorption of X-rays and described this phenomenon using the Bohr theory, applied quantum principles to the interpretation of photoelectron spectra, and gave a systematic classification of X-ray spectra. The studies of X-ray spectra were important for elucidating the structure of the internal electron shells of atoms (optical spectra are determined by the outer shells). Thus, the results of experiments conducted together with Alexandre Dauvillier, revealed the shortcomings of the existing schemes for the distribution of electrons in atoms; these difficulties were eliminated by Edmund Stoner. Another result was the elucidation of the insufficiency of the Sommerfeld formula for determining the position of lines in X-ray spectra; this discrepancy was eliminated after the discovery of the electron spin. In 1925 and 1926, Leningrad physicist Orest Khvolson nominated the de Broglie brothers for the Nobel Prize for their work in the field of X-rays.

Matter and wave–particle duality

Studying the nature of X-ray radiation and discussing its properties with his brother Maurice, who considered these rays to be some kind of combination of waves and particles, contributed to Louis de Broglie's awareness of the need to build a theory linking particle and wave representations. In addition, he was familiar with the works (1919–1922) of Marcel Brillouin, which proposed a hydrodynamic model of an atom and attempted to relate it to the results of Bohr's theory. The starting point in the work of Louis de Broglie was the idea of A. Einstein about the quanta of light. In his first article on this subject, published in 1922, the French scientist considered blackbody radiation as a gas of light quanta and, using classical statistical mechanics, derived the Wien radiation law in the framework of such a representation. In his next publication, he tried to reconcile the concept of light quanta with the phenomena of interference and diffraction and came to the conclusion that it was necessary to associate a certain periodicity with quanta. In this case, light quanta were interpreted by him as relativistic particles of very small mass.

It remained to extend the wave considerations to any massive particles, and in the summer of 1923 a decisive breakthrough occurred. De Broglie outlined his ideas in a short note "Waves and quanta" (French: Ondes et quanta, presented at a meeting of the Paris Academy of Sciences on September 10, 1923), which marked the beginning of the creation of wave mechanics. In this paper, the scientist suggested that a moving particle with energy E and velocity v is characterized by some internal periodic process with a frequency  (later known as Compton frequency), where

(later known as Compton frequency), where  is Planck's constant. To reconcile these considerations, based on the quantum principle, with the ideas of special relativity, de Broglie was forced to associate a "fictitious wave" with a moving body, which propagates with the phase velocity

is Planck's constant. To reconcile these considerations, based on the quantum principle, with the ideas of special relativity, de Broglie was forced to associate a "fictitious wave" with a moving body, which propagates with the phase velocity  . Such a wave, which later received the name phase wave, or de Broglie wave, in the process of body movement remains in phase with the internal periodic process. Having then examined the motion of an electron in a closed orbit, the scientist showed that the requirement for phase matching directly leads to the quantum Bohr-Sommerfeld condition, that is, to quantize the angular momentum. In the next two notes (reported at the meetings on September 24 and October 8, respectively), de Broglie came to the conclusion that the particle velocity is equal to the group velocity of phase waves, and the particle moves along the normal to surfaces of equal phase. In the general case, the trajectory of a particle can be determined using Fermat's principle (for waves) or the principle of least action (for particles), which indicates a connection between geometric optics and classical mechanics.

. Such a wave, which later received the name phase wave, or de Broglie wave, in the process of body movement remains in phase with the internal periodic process. Having then examined the motion of an electron in a closed orbit, the scientist showed that the requirement for phase matching directly leads to the quantum Bohr-Sommerfeld condition, that is, to quantize the angular momentum. In the next two notes (reported at the meetings on September 24 and October 8, respectively), de Broglie came to the conclusion that the particle velocity is equal to the group velocity of phase waves, and the particle moves along the normal to surfaces of equal phase. In the general case, the trajectory of a particle can be determined using Fermat's principle (for waves) or the principle of least action (for particles), which indicates a connection between geometric optics and classical mechanics.

This theory set the basis of wave mechanics. It was supported by Einstein, confirmed by the electron diffraction experiments of G P Thomson and Davisson and Germer, and generalized by the work of Schrödinger.

However, this generalization was statistical and was not approved of by de Broglie, who said "that the particle must be the seat of an internal periodic movement and that it must move in a wave in order to remain in phase with it was ignored by the actual physicists [who are] wrong to consider a wave propagation without localization of the particle, which was quite contrary to my original ideas."

From a philosophical viewpoint, this theory of matter-waves has contributed greatly to the ruin of the atomism of the past. Originally, de Broglie thought that real wave (i.e., having a direct physical interpretation) was associated with particles. In fact, the wave aspect of matter was formalized by a wavefunction defined by the Schrödinger equation, which is a pure mathematical entity having a probabilistic interpretation, without the support of real physical elements. This wavefunction gives an appearance of wave behavior to matter, without making real physical waves appear. However, until the end of his life de Broglie returned to a direct and real physical interpretation of matter-waves, following the work of David Bohm. The de Broglie–Bohm theory is today the only interpretation giving real status to matter-waves and representing the predictions of quantum theory.

Conjecture of an internal clock of the electron

In his 1924 thesis, de Broglie conjectured that the electron has an internal clock that constitutes part of the mechanism by which a pilot wave guides a particle. Subsequently, David Hestenes has proposed a link to the zitterbewegung that was suggested by Erwin Schrödinger.

While attempts at verifying the internal clock hypothesis and measuring clock frequency are so far not conclusive, recent experimental data is at least compatible with de Broglie's conjecture.

Non-nullity and variability of mass

According to de Broglie, the neutrino and the photon have rest masses that are non-zero, though very low. That a photon is not quite massless is imposed by the coherence of his theory. Incidentally, this rejection of the hypothesis of a massless photon enabled him to doubt the hypothesis of the expansion of the universe.

In addition, he believed that the true mass of particles is not constant, but variable, and that each particle can be represented as a thermodynamic machine equivalent to a cyclic integral of action.

Generalization of the principle of least action

In the second part of his 1924 thesis, de Broglie used the equivalence of the mechanical principle of least action with Fermat's optical principle: "Fermat's principle applied to phase waves is identical to Maupertuis' principle applied to the moving body; the possible dynamic trajectories of the moving body are identical to the possible rays of the wave." This equivalence had been pointed out by Hamilton a century earlier, and published by him around 1830, in an era where no experience gave proof of the fundamental principles of physics being involved in the description of atomic phenomena.

Up to his final work, he appeared to be the physicist who most sought that dimension of action which Max Planck, at the beginning of the 20th century, had shown to be the only universal unity (with his dimension of entropy).

Duality of the laws of nature

That idea seems to match the continuous–discontinuous duality, since its dynamics could be the limit of its thermodynamics when transitions to continuous limits are postulated. It is also close to that of Leibniz, who posited the necessity of "architectonic principles" to complete the system of mechanical laws.

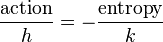

However, according to him, there is less duality, in the sense of opposition, than synthesis (one is the limit of the other) and the effort of synthesis is constant according to him, like in his first formula, in which the first member pertains to mechanics and the second to optics:

Neutrino theory of light

This theory, which dates from 1934, introduces the idea that the photon is equivalent to the fusion of two Dirac neutrinos. It is not currently accepted by the majority of physicists.

Hidden thermodynamics

De Broglie's final idea was the hidden thermodynamics of isolated particles. It is an attempt to bring together the three furthest principles of physics: the principles of Fermat, Maupertuis, and Carnot.

In this work, action becomes a sort of opposite to entropy, through an equation that relates the only two universal dimensions of the form:

As a consequence of its great impact, this theory brings back the uncertainty principle to distances around extrema of action, distances corresponding to reductions in entropy.

Honors and awards

- 1929 Nobel Prize in Physics

- 1929 Henri Poincaré Medal

- 1932 Albert I of Monaco Prize

- 1938 Max Planck Medal

- 1938 Fellow, Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences

- 1944 Fellow, Académie française

- 1952 Kalinga Prize

- 1953 Fellow, Royal Society

See also

In Spanish: Louis-Victor de Broglie para niños

In Spanish: Louis-Victor de Broglie para niños