Melville Fuller facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Melville Fuller

|

|

|---|---|

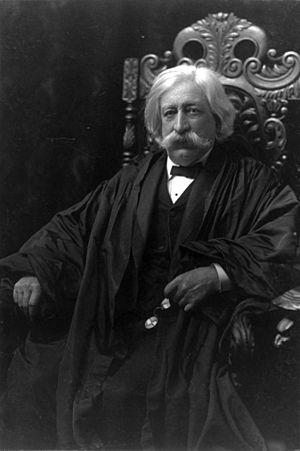

Fuller in 1908

|

|

| 8th Chief Justice of the United States | |

| In office October 8, 1888 – July 4, 1910 |

|

| Nominated by | Grover Cleveland |

| Preceded by | Morrison Waite |

| Succeeded by | Edward Douglass White |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

Melville Weston Fuller

February 11, 1833 Augusta, Maine, U.S. |

| Died | July 4, 1910 (aged 77) Sorrento, Maine, U.S. |

| Resting place | Graceland Cemetery, Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 10 |

| Education | Bowdoin College Harvard University |

| Signature | |

Melville Weston Fuller (February 11, 1833 – July 4, 1910) was an American politician, attorney, and jurist who served as the eighth chief justice of the United States from 1888 until his death in 1910. Staunch conservatism marked his tenure on the Supreme Court, exhibited by his tendency to support unfettered free enterprise and to oppose broad federal power. He wrote major opinions on the federal income tax, the Commerce Clause, and citizenship law, and he took part in important decisions about racial segregation and the liberty of contract. Those rulings often faced criticism in the decades during and after Fuller's tenure, and many were later overruled or abrogated. The legal academy has generally viewed Fuller negatively, although a revisionist minority has taken a more favorable view of his jurisprudence.

Born in Augusta, Maine, Fuller established a legal practice in Chicago after graduating from Bowdoin College. A Democrat, he became involved in politics, campaigning for Stephen A. Douglas in the 1860 presidential election. During the Civil War, he served a single term in the Illinois House of Representatives, where he opposed the policies of President Abraham Lincoln. Fuller became a prominent attorney in Chicago and was a delegate to several Democratic national conventions. He declined three separate appointments offered by President Grover Cleveland before accepting the nomination to succeed Morrison Waite as chief justice. Despite some objections to his political past, Fuller won Senate confirmation in 1888. He served as chief justice until his death in 1910, gaining a reputation for collegiality and able administration.

Fuller's jurisprudence was conservative, focusing strongly on states' rights, limited federal power, and economic liberty. His majority opinion in Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Co. (1895) ruled a federal income tax to be unconstitutional; the Sixteenth Amendment later superseded the decision. Fuller's opinion in United States v. E. C. Knight Co. (1895) narrowly interpreted Congress's authority under the Commerce Clause, limiting the reach of the Sherman Act and making government prosecution of antitrust cases more difficult. In Lochner v. New York (1905), Fuller agreed with the majority that the Constitution forbade states from enforcing wage-and-hour restrictions on businesses, contending that the Due Process Clause prevents government infringement on one's liberty to control one's property and business affairs. Fuller joined the majority in the now-reviled case of Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), in which the Court articulated the doctrine of separate but equal and upheld Jim Crow laws. He argued in the Insular Cases that residents of the territories are entitled to constitutional rights, but he dissented when, in United States v. Wong Kim Ark (1898), the majority ruled in favor of birthright citizenship.

Many of Fuller's decisions did not stand the test of time. His views on economic liberty were squarely rejected by the Court during the New Deal era, and the Plessy opinion was unanimously reversed in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). Fuller's historical reputation has been generally unfavorable, with many scholars arguing that he was overly deferential to corporations and the wealthy. While a resurgence of conservative legal thought has brought Fuller new defenders, an increase in racial awareness has also led to new scrutiny of his vote in Plessy. In 2021, Kennebec County commissioners voted unanimously to remove a statue of Fuller from public land, aiming to dissociate the county from racial segregation.

Contents

Early life

Melville Weston Fuller was born on February 11, 1833, in Augusta, Maine, the second son of Frederick Augustus Fuller and his wife, Catherine Martin (née Weston). His maternal grandfather, Nathan Weston, served on the Supreme Court of Maine, and his paternal grandfather was a probate judge. His father practiced law in Augusta. Three months after Fuller was born, his mother sued successfully for divorce; she and her children moved into Judge Weston's home. In 1849, the sixteen-year-old Fuller enrolled at Bowdoin College, from which he graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1853. He studied law in an uncle's office before spending six months at Harvard Law School. While he did not receive a degree from Harvard, his attendance made him the first chief justice to have received formal academic legal training. Fuller was admitted to the Maine bar in 1855 and clerked for another uncle in Bangor. Later that year, he moved back to Augusta to become the editor of The Age, Maine's primary Democratic newspaper, in partnership with another uncle. Fuller was elected to Augusta's common council in March 1856, serving as the council's president and as the city solicitor.

Career

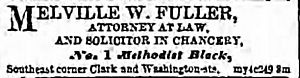

In 1856, Fuller left Maine for Chicago, Illinois. The city presented Fuller, a steadfast Democrat, with greater opportunities and a more favorable political climate. In addition, a broken engagement likely encouraged him to leave his hometown. Fuller accepted a position with a local law firm, and he also became involved in politics. Although Fuller opposed slavery, he considered it an issue for the states rather than the federal government. He supported the Kansas–Nebraska Act, which repealed the Missouri Compromise and allowed Kansas and Nebraska to determine the slavery issue themselves. Fuller opposed both abolitionists and secessionists, arguing instead for compromise. He campaigned for Stephen A. Douglas both in his successful 1858 Senate campaign against Abraham Lincoln and in his unsuccessful bid against Lincoln in the 1860 presidential election.

When the American Civil War broke out in 1861, Fuller supported military action against the Confederacy. However, he opposed the Lincoln Administration's handling of the war, and he decried many of Lincoln's actions as unconstitutional. Fuller was elected as a Democratic delegate to the failed 1862 Illinois constitutional convention. He helped develop a gerrymandered system for congressional apportionment, and he joined his fellow Democrats in supporting provisions that prohibited African-Americans from voting or settling in the state. He also advocated for court reform and for banning banks from printing of paper money. Although the convention adopted many of his proposals, voters rejected the proposed constitution in June 1862.

In November 1862, Fuller was narrowly elected to a seat in the Illinois House of Representatives as a Democrat. The majority-Democrat legislature clashed with Republican governor Richard Yates and opposed the wartime policies of President Lincoln. Fuller spoke in opposition to the Emancipation Proclamation, arguing that it violated state sovereignty. He supported the Corwin Amendment, which would have prevented the federal government from outlawing slavery. Fuller opposed Lincoln's decision to suspend the writ of habeas corpus, believing it violated civil liberties. Yates ultimately adjourned the legislature over the vehement objections of Fuller and the Democrats. The frustrated Fuller never sought legislative office again, although he continued taking part in Democratic party politics.

Fuller maintained a successful legal practice, arguing on behalf of many corporations and businessmen. He represented the city of Chicago in a land dispute with the Illinois Central Railroad. In 1869, he took on what became his most significant case: defending Chicago clergyman Charles E. Cheney, whom the Episcopal Church was attempting to remove because he disagreed with church teaching on baptismal regeneration. Believing the ecclesiastical court to be biased against Cheney, Fuller filed suit in Chicago Superior Court, arguing that Cheney possessed a property right in his position. The Superior Court agreed and entered an injunction against the ecclesiastical court's proceedings. On appeal, the Supreme Court of Illinois reversed the injunction, holding that the civil courts could not review church disciplinary proceedings. The ecclesiastical court found Cheney guilty, but he refused to leave his pulpit. The matter returned to the courts, where Fuller argued that only the local congregation had the right to remove Cheney. The Supreme Court of Illinois ultimately agreed, holding that the congregation's property was not under the purview of Episcopal Church leadership. Fuller's defense of Cheney garnered him national prominence.

Beginning in 1871, Fuller also litigated before the Supreme Court of the United States, arguing numerous cases. His legal practice involved many areas of law, and he became one of Chicago's most highly paid lawyers. He remained involved in the politics of the Democratic Party, serving as a delegate to the party convention in 1872, 1876, and 1880. Fuller supported a strict construction of the U.S. Constitution. He firmly opposed the printing of paper money, and he spoke out against the Supreme Court's 1884 decision in Juilliard v. Greenman upholding Congress's power to issue it. He was a supporter of states' rights and generally advocated for limited government. Fuller strongly supported President Grover Cleveland, a fellow Democrat, who agreed with many of his views. Cleveland successively attempted to appoint Fuller to chair the United States Civil Service Commission, to serve as Solicitor General, and to be a United States Pacific Railway Commissioner, but Fuller declined each nomination.

Nomination to Supreme Court

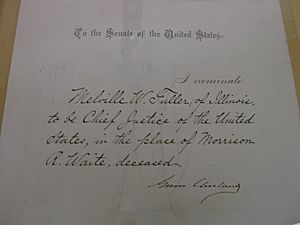

On March 23, 1888, Chief Justice Morrison Waite died, creating a Supreme Court vacancy for President Cleveland to fill. The Senate was narrowly under Republican control, so it was necessary for Cleveland to nominate someone who could obtain bipartisan support. Cleveland also sought to appoint a candidate who was sixty years of age or younger, since an older nominee would likely be unable to serve for very long. He considered Vermont native Edward J. Phelps, the ambassador to the United Kingdom, but the politically influential Irish-American community, which viewed him as an Anglophile, opposed him. Furthermore, the sixty-six-year-old Phelps was thought to be too old for the job, and the Supreme Court already had one justice from New England. Senator George Gray was considered, but appointing him would create a vacancy in the closely divided Senate. Cleveland eventually decided that he wanted to appoint someone from Illinois, both for political reasons and because the court had no justices from the Seventh Circuit, which included Illinois. Fuller, who had become a confidant of Cleveland, encouraged the President to appoint John Scholfield, who served on the Illinois Supreme Court. Cleveland offered the position to Scholfield, but he declined, apparently because his wife was too rustic for urban life in Washington, D.C. Fuller was considered because of the efforts of his friends, many of whom had written letters to Cleveland in support of him. At fifty-five years old, Fuller was young enough for the position, and Cleveland approved of his reputation and political views. In addition, Illinois Republican senator Shelby Cullom expressed support, convincing Cleveland that Fuller would likely receive bipartisan support in the Senate. Cleveland thus offered Fuller the nomination, which he accepted reluctantly. Fuller was formally nominated on April 30.

Public reaction to Fuller's nomination was mixed: Some newspapers lauded his character and professional career, while others criticized his comparative obscurity and his lack of experience in the federal government. The nomination was referred to the Senate Judiciary Committee, chaired by Vermont Republican George F. Edmunds. Edmunds was displeased that his friend Phelps had not been appointed, so he delayed committee action and endeavored to sink Fuller's nomination. The Republicans seized upon Fuller's time in the Illinois Legislature, when he had opposed many of Lincoln's wartime policies. They portrayed him as a Copperhead – an anti-war Northern Democrat – and published a tract claiming that "[t]he records of the Illinois legislature of 1863 are black with Mr. Fuller's unworthy and unpatriotic conduct". Some Illinois Republicans, including Lincoln's son Robert, came to Fuller's defense, arguing that his actions were imprudent but not an indicator of disloyalty. Fuller's detractors claimed he would reverse the Supreme Court's ruling in the recent legal-tender case of Juilliard; his defenders replied he would be faithful to precedent. Vague allegations of professional improprieties were levied, but an investigation failed to substantiate them. The Judiciary Committee took no action on the nomination, and many believed that Edmunds was attempting to hold it off until after the 1888 presidential election. Cullom demanded an immediate vote, fearing that delay on Fuller's nomination could harm Republicans' prospects of winning Illinois. The committee reported the nomination without recommendation on July 2, 1888.

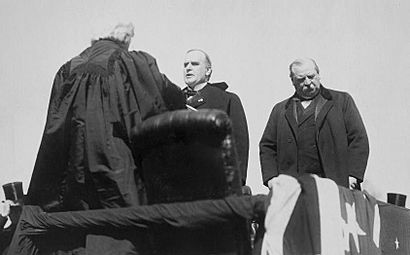

The full Senate took up Fuller's nomination on July 20. Several prominent Republican senators, including William M. Evarts of New York, William Morris Stewart of Nevada, and Edmunds, spoke against the nomination, arguing that Fuller was a disloyal Copperhead who would misinterpret the Reconstruction Amendments and roll back the progress made by the Civil War. Illinois's two Republican senators, Cullom and Charles B. Farwell defended Fuller's actions and character. Cullom read an anti-Lincoln speech that Phelps, Edmunds's choice for the position, had given. He accused Edmunds of hypocrisy and insincerity, saying he was simply resentful that Phelps had not been chosen. The Democratic senators did not participate in the debate, aiming to let the Republicans squabble among themselves. When the matter came to a vote, Fuller was confirmed 41 to 20, with 15 absences. Ten Republicans, including Republican National Committee chair Matthew Quay and two senators from Fuller's home state of Maine, joined the Democrats in supporting Fuller's nomination. Fuller took the judicial oath on October 8, 1888, formally becoming Chief Justice of the United States.

Chief justice

Fuller served twenty-two years as chief justice, remaining in the center chair until his death in 1910. Although he lacked legal genius, his potent administrative skills made him a capable manager of the court's business. Hoping to increase the Court's collegiality, Fuller introduced the practice of the justices' shaking hands before their private conferences. He successfully maintained more-or-less cordial relationships among the justices, many of whom had large egos and difficult tempers. His collegiality notwithstanding, Fuller presided over a divided court: the justices split 5–4 sixty-four times during his tenure, more often than in subsequent years. Fuller himself, however, wrote few dissents, disagreeing with the majority in only 2.3 percent of cases. Fuller was the first chief justice to lobby Congress directly in support of legislation, successfully urging the adoption of the Circuit Courts of Appeals Act of 1891. The act established intermediate appellate courts, which reduced the Supreme Court's substantial backlog and allowed it to decide cases in a timely manner. As chief justice, Fuller was generally responsible for assigning the authorship of the court's majority opinions. He tended to use this power modestly, often assigning major cases to other justices while retaining duller ones for himself. According to legal historian Walter F. Pratt, Fuller's writing style was "nondescript"; his opinions were lengthy and contained numerous quotations. Justice Felix Frankfurter opined that Fuller was "not an opinion writer whom you read for literary enjoyment", while the scholar G. Edward White characterized his style as "diffident and not altogether successful".

In 1893, Cleveland offered to appoint Fuller to be secretary of state. He declined, saying he enjoyed his work as chief justice and contending that accepting a political appointment would harm the Supreme Court's reputation for impartiality. Remaining on the Court, he accepted a seat on an 1897 commission to arbitrate the Venezuelan boundary dispute, and he served ten years on the Permanent Court of Arbitration. Fuller's health declined after 1900, and scholar David Garrow suggests that his "growing enfeeblement" inhibited his work. In what biographer Willard King calls "[p]erhaps the worst year in the history of the Court" – the term from October 1909 to May 1910 – two justices died and one became fully incapacitated; Fuller's weakened state compounded the problem. Fuller died that July. President William Howard Taft nominated Associate Justice Edward Douglass White to replace him.

Personal life

Fuller was married twice, first to Calista Reynolds, whom he wed in 1858. They had two children before she died of tuberculosis in 1864. Fuller remarried in 1866, wedding Mary Ellen Coolbaugh, the daughter of William F. Coolbaugh. The couple had an additional eight children, and they remained married until her death in 1904. A member of the Chicago Literary Club, Fuller was interested in poetry and other forms of literature; his personal library held over six thousand books.

During his confirmation, Fuller's mustache produced what law professor Todd Peppers called "a curious national anxiety". No Chief Justice had ever before had a mustache, and numerous newspapers debated the propriety of Fuller's facial hair. The New York Sun praised it as "uncommonly luxuriant and beautiful", while the Jackson Standard quipped that "Fuller's mustache is a good quality for a Democratic politician—it shuts his mouth." After Fuller's confirmation, the Sun switched course: it denounced his "deplorable moustaches", speculating they would distract attorneys and "detract from the dignity" of the Court. The column triggered further debate in the nation's newspapers, with much of the press coming to Fuller's defense. The commentary notwithstanding, Fuller kept the mustache.

Death

While at his summer home in Sorrento, Maine, Fuller died on July 4, 1910, of a heart attack. Upon hearing of his death, President Taft praised Fuller as "a great judge"; Theodore Roosevelt said "I admired the Chief Justice as a fearless and upright judge, and I was exceedingly attached to him personally." James E. Freeman, who later served as the Episcopal Bishop of Washington, conducted the funeral service. Fuller was buried at Graceland Cemetery in Chicago.

Legacy

Fuller's time on the Supreme Court has often been roundly criticized or overlooked altogether. His support of the widely execrated Plessy and Lochner decisions has been particularly responsible for his low historical reputation. Many Fuller Court decisions were later overruled; its positions on economic regulation and labor fared particularly poorly. Fuller's rulings were often favorable to corporations, and some scholars have claimed that the Fuller Court was biased towards big business and against the working class. Fuller wrote few consequential majority opinions, leading Yale professor John P. Frank to remark that "[i]f the measure of distinction is influence on the life of our own times, Fuller's score is as close to zero as any man's could be who held his high office so long". In addition, as William Rehnquist – himself a chief justice – noted, Fuller's more assertive colleagues Holmes and Harlan overshadowed him in the eyes of history. Yet the Fuller Court's jurisprudence was also a key source of the legal academy's criticism. Asserting that its justices "ignored the Fundamental Law", Princeton professor Alpheus T. Mason argued that "[t]he tribunal Fuller headed was a body dominated by fear—the fear of populists, of socialists, and communists, of numbers, majorities and democracy".

However, the growth of conservative legal thought in the late 20th century has brought Fuller new supporters. A 1993 survey of judges and legal academics found that Fuller's reputation, while still categorized as "average", had risen from the level recorded in a 1970 assessment. In a 1995 book, James W. Ely argued that the traditional criticisms of the Fuller Court are flawed, maintaining that its decisions were based on principle instead of partisanship. He noted that Fuller and his fellow justices rendered rulings that generally conformed with contemporaneous public opinion. Both Bruce Ackerman and Howard Gillman defended the Fuller Court on similar grounds, arguing that the justices' decisions fit in with the era's zeitgeist. Lawrence Reed of the Mackinac Center for Public Policy wrote in 2006 that Fuller was "a model Chief Justice", favorably citing his economic jurisprudence. While these revisionist ideas have become influential in the scholarly academy, they have not attained universal support: many academics continue to favor more critical views of the Fuller Court. Yale professor Owen M. Fiss, himself sympathetic to the revisionists' views, noted in 1993 that "by all accounts", the Fuller Court "ranks among the worst". In a 1998 review of Ely's book, law professor John Cary Sims argued that Fuller and his fellow justices failed to fulfill their obligation to go "against the prevailing political winds" instead of simply deferring to the majority. George Skouras, writing in 2011, rejected the ideas of Ely, Ackerman, and Gillman, agreeing instead with the Progressive argument that the Fuller Court favored corporations over vulnerable Americans. Fuller's legacy came under substantial scrutiny amidst racial unrest in 2020, with many condemning him for his vote in Plessy.

Statue

In 2013, a statue of Fuller, donated by a cousin, was installed on the lawn in front of Augusta's Kennebec County Courthouse. With Black Lives Matter protests and other attention in 2020, focus on the Plessy decision led to debate about the appropriateness of the statue's placement. In August 2020, the Maine Supreme Judicial Court requested that the statue be removed, citing Plessy. Kennebec County commissioners held a public hearing in December; a majority of participants favored the statue's removal. In February 2021, the county commissioners voted unanimously to move the statue from county property, citing a desire to dissociate the county from racial segregation. Commissioners appointed a committee to identify a new home for the statue. In April 2021, the original donor offered to take the statue back, agreeing to pay the costs for removing it. County commissioners accepted the offer later that month; they agreed that the statue could remain in front of the courthouse for up to a year while the original donor attempted to find a new location where it can be displayed. In February 2022, the statue was removed and placed in storage.

Images for kids

-

In this 1895 political cartoon, Fuller is depicted placing a dunce cap with the words "INCOME TAX DECISION" on President Cleveland, who had signed the tax into law. The cartoon appeared in the Judge magazine; it was accompanied by a quotation from Senator David B. Hill praising the Court's decision.

See also

- Fuller Park, a community area of Chicago, named for him.

- Fuller-Weston House, historic home in Augusta, Maine, where Fuller lived