Michael Servetus facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Michael Servetus

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | Unknown, possibly 29 September 1511 |

| Died | 27 October 1553 (aged 42) Geneva, Republic of Geneva

|

| Alma mater | University of Paris |

| Occupation | Theologian, physician, editor, translator |

| Theological work | |

| Era | Renaissance |

| Tradition or movement | Renaissance humanism |

| Main interests | Theology, medicine |

| Notable ideas | Nontrinitarian Christology, pulmonary circulation |

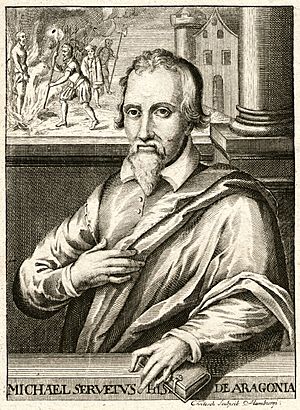

Michael Servetus (/sərˈviːtəs/; Spanish: Miguel Serveto as real name; French: Michel Servet; also known as Miguel Servet, Miguel de Villanueva, Revés, or Michel de Villeneuve; 29 September 1509 or 1511 – 27 October 1553) was a Spanish theologian, physician, cartographer, and Renaissance humanist. He was the first European to correctly describe the function of pulmonary circulation, as discussed in Christianismi Restitutio (1553). He was a polymath versed in many sciences: mathematics, astronomy and meteorology, geography, human anatomy, medicine and pharmacology, as well as jurisprudence, translation, poetry, and the scholarly study of the Bible in its original languages.

He is renowned in the history of several of these fields, particularly medicine. He participated in the Protestant Reformation, and later rejected the Trinity doctrine and mainstream Catholic Christology. After being condemned by Catholic authorities in France, he fled to Calvinist Geneva where he was denounced by John Calvin himself and burned at the stake for heresy by order of the city's governing council.

Contents

Life

Early life and education

For a long time, it was held that Servetus was probably born in 1511 in Villanueva de Sigena in the Kingdom of Aragon, present-day Spain. The day of 29 September has been conventionally proposed for his birth, due to the fact that 29 September is Saint Michael's day according to the Catholic calendar of saints, but there is no evidence supporting this date. Some sources give an earlier date based on Servetus' own occasional claim of having been born in 1509. However, in 2002 a paper published by Francisco Javier González Echeverría and María Teresa Ancín suggested that he was born in Tudela, Kingdom of Navarre. It has also been held that his true name was De Villanueva according to the letters of his French naturalization (Chamber des Comptes, Royal Chancellorship and Parlement of Grenoble) and the registry at the University of Paris.

The ancestors of his father came from the hamlet of Serveto, in the Aragonese Pyrenees. His father was a notary of Christian ancestors from the lower nobility (infanzón), who worked at the nearby Monastery of Santa Maria de Sigena. It was long believed that Servetus had just two brothers: Juan, who was a Catholic parish priest, and Pedro, who was a notary. But, it has been recently documented that Servetus actually had two more brothers (Antón and Francisco) and at least three sisters (Catalina, Jeronima, and Juana). Although Servetus declared during his trial in Geneva that his parents were "Christians of ancient race", and that he never had any communication with Jews, his maternal line actually descended from the Zaportas (or Çaportas), a wealthy and socially relevant family from the Barbastro and Monzón areas in Aragon. This was demonstrated by a notarial protocol published in 1999.

Servetus' family used a nickname, "Revés", according to an old tradition in rural Spain of using alternate names for families across generations. The origin of the Revés nickname may have been that a member of a (probably distinguished) family living in Villanueva with the surname Revés established blood ties with the Servet family, thus uniting both family names for the next generations.

Education

Servetus attended the Grammar Studium in Sariñena, Aragón, near Villanueva de Sijena, under master Domingo Manobel until 1520. From course 1520/1521 to 1522/1523, Michael Servetus was a student of the Liberal Arts in the primitive University of Zaragoza, a Studium Generale of Arts. The Studium was ruled by the Archbishop of Saragossa, the Rector, the High Master ("Maestro Mayor"), and four "Masters of Arts", which resembled Art professors in the Arts Faculties of other primitive universities. Servetus studied under High Master Gaspar Lax, and masters Exerich, Ansias, and Miranda. During those years this education center had been significantly influenced by Erasmus's ideas. Ansias and Miranda died soon, and two new professors were appointed: Juan Lorenzo Carnicer and Villalpando. In 1523 he got his BA and next year his MA. From course 1525/1526 ahead, Servetus became one of the four Masters of Arts in the Studium, and for unknown reasons, he traveled to Salamanca in February 1527. But on 28 March 1527, also for unknown reasons, master Michael Servetus had a brawl with High Master (and uncle) Gaspard Lax, and this probably was the cause of his expulsion from the Studium, and his exile from Spain for the Studium of Toulouse, trying to avoid the strong influence of Gaspar Lax in any Spanish Studium Generale.

Near 1527 Servetus attended the University of Toulouse where he studied law. Servetus could have had access to forbidden religious books, some of them maybe Protestant, while he was studying in this city.

Career

In 1530 Servetus joined the retinue of Emperor Charles V as page or secretary to the emperor's confessor, Juan de Quintana. Servetus travelled through Italy and Germany and attended Charles' coronation as Holy Roman Emperor in Bologna. He was outraged by the pomp and luxury displayed by the Pope and his retinue, and so decided to follow the path of reformation. It is not known when Servetus left the imperial entourage, but in October 1530 he visited Johannes Oecolampadius in Basel, staying there for about ten months, probably supporting himself as a proofreader for a local printer. By this time, he was already spreading his theological beliefs. In May 1531 he met Martin Bucer and Wolfgang Fabricius Capito in Strasbourg.

Two months later, in July 1531, Servetus published De Trinitatis Erroribus (On the Errors of the Trinity). The next year he published the work Dialogorum de Trinitate (Dialogues on the Trinity) and the supplementary work De Iustitia Regni Christi (On the Justice of Christ's Reign) in the same volume. After the persecution of the Inquisition, Servetus assumed the name "Michel de Villeneuve" while he was staying in France. He studied at the Collège de Calvi in Paris in 1533. Servetus also published the first French edition of Ptolemy's Geography. He dedicated his first edition of Ptolemy and his edition of the Bible to his patron Hugues de la Porte. While in Lyon, Symphorien Champier, a medical humanist, had been his patron. Servetus wrote a pharmacological treatise in defence of Champier against Leonhart Fuchs In Leonardum Fucsium Apologia (Apology against Leonard Fuchs). Working also as a proofreader, he published several more books, which dealt with medicine and pharmacology (such as his Syruporum universia ratio (Complete Explanation of the Syrups)), for which he gained fame.

After an interval, Servetus returned to Paris to study medicine in 1536. In Paris, his teachers included Jacobus Sylvius, Jean Fernel, and Johann Winter von Andernach, who hailed him with Andrea Vesalius as his most able assistant in dissections. During these years, he wrote his Manuscript of the Complutense, an unpublished compendium of his medical ideas. Servetus taught mathematics and astrology while he studied medicine. He predicted an occultation of Mars by the Moon, which along with his teaching, generated much envy among the medicine teachers. His teaching classes were suspended by the Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, Jean Tagault, and Servetus wrote his Apologetic Discourse of Michel de Villeneuve in Favour of Astrology and against a Certain Physician against him. Tagault later argued for the death penalty in the judgment of the University of Paris against Servetus, who was accused of teaching De Divinatione by Cicero. Finally, the sentence was reduced to the withdrawal of this edition. As a result of the risks and difficulties of studying medicine at Paris, Servetus decided to go to Montpellier to finish his medical studies, maybe thanks to his teacher Sylvius who did exactly the same as a student. There Servetus became a Doctor of Medicine in 1539. After that he lived at Charlieu. A jealous physician ambushed and tried to kill Servetus, but Servetus defended himself and injured one of the attackers in a sword fight. He was in prison for several days because of this incident.

Working at Vienne

After his studies in medicine, Servetus started a medical practice. He became the personal physician to Pierre Palmier, Archbishop of Vienne and was the physician to Guy de Maugiron, the lieutenant governor of Dauphiné. Thanks to the printer Jean Frellon II, acquaintance of John Calvin and friend of Michel, Servetus and Calvin began to correspond. Calvin used the pseudonym "Charles d'Espeville". Servetus also became a French citizen, using his "De Villeneuve" persona, by the Royal Process (1548–1549) of French Naturalization, issued by Henri II of France.

In 1553 Michael Servetus published another religious work with further anti-trinitarian views entitled Christianismi Restitutio (The Restoration of Christianity), a work that sharply rejected the idea of predestination as the idea that God condemned souls to Hell regardless of worth or merit. God, insisted Servetus, condemns no one who does not condemn himself through thought, word, or deed. This work also includes the first published description of the pulmonary circulation in Europe, though it's thought to be based on work by 13th century Syrian polymath ibn al-Nafis.

Servetus had sent an early version of his book to Calvin. To Calvin, who had published his summary of Christian doctrine Institutio Christianae Religionis (Institutes of the Christian Religion) in 1536, Servetus' latest book was an attack on historical Nicene Christian doctrine and a misinterpretation of the biblical canon. Calvin sent a copy of his own book as his reply. Servetus promptly returned it, thoroughly annotated with critical observations. Calvin wrote to Servetus, "I neither hate you nor despise you; nor do I wish to persecute you; but I would be as hard as iron when I behold you insulting sound doctrine with so great audacity". In time, their correspondence grew more heated until Calvin ended it. Servetus sent Calvin several more letters, to which Calvin took offense. Thus, Calvin's frustrations with Servetus seem to have been based mainly on Servetus's criticisms of Calvinist doctrine, but also on his tone, which Calvin considered inappropriate. Calvin revealed these frustrations with Servetus when writing to his friend William Farel on 13 February 1546:

Servetus has just sent me a long volume of his ravings. If I consent he will come here, but I will not give my word; for if he comes here, if my authority is worth anything, I will never permit him to depart alive (Latin: Si venerit, modo valeat mea autoritas, vivum exire nunquam patiar).

Imprisonment and execution

On 16 February 1553, Michael Servetus while in Vienne, France, was denounced as a heretic by Guillaume de Trie (a rich merchant who had taken refuge in Geneva). On 4 April 1553, Servetus was arrested by Roman Catholic authorities and imprisoned in Vienne. He escaped from prison three days later. On 17 June, he was convicted of heresy in his absence.

Meaning to flee to Italy, Servetus inexplicably stopped in Geneva, where Calvin and his Reformers had denounced him. On 13 August, he attended a sermon by Calvin at Geneva. He was arrested after the service and again imprisoned, and all his property was confiscated.

Servetus was tried and on 24 October sentenced to death by burning for denying the Trinity and infant baptism. On 27 October, Servetus was executed atop a pyre of his own books at the Plateau of Champel at the edge of Geneva. Historians record his last words as: "Jesus, Son of the Eternal God, have mercy on me."

Legacy

Sebastian Castellio and countless others denounced this execution and became harsh critics of Calvin because of the whole affair.

Some other anti-trinitarian thinkers began to be more cautious in expressing their views: Martin Cellarius, Lelio Sozzini and others either ceased writing or wrote only in private. The fact that Servetus was dead meant that his writings could be distributed more widely, though others such as Giorgio Biandrata developed them in their own names.

The writings of Servetus influenced the beginnings of the Unitarian movement in Poland and Transylvania. Peter Gonesius's advocacy of Servetus' views led to the separation of the Polish brethren from the Calvinist Reformed Church in Poland, and laid the foundations for the Socinian movement which fostered the early Unitarians in England like John Biddle.

Theology

In his first two books (De trinitatis erroribus, and Dialogues on the Trinity plus the supplementary De Iustitia Regni Christi) Servetus rejected the classical conception of the Trinity, stating that it was not based on the Bible. He argued that it arose from teachings of Greek philosophers, and he advocated a return to the simplicity of the Gospels and the teachings of the early Church Fathers that he believed predated the development of Nicene trinitarianism. Servetus hoped that the dismissal of the trinitarian dogma would make Christianity more appealing to believers in Judaism and Islam, which had preserved the unity of God in their teachings. According to Servetus, trinitarians had turned Christianity into a form of "tritheism", or belief in three gods. Servetus affirmed that the divine Logos, the manifestation of God and not a separate divine Person, was incarnated in a human being, Jesus, when God's spirit came into the womb of the Virgin Mary. Only from the moment of conception was the Son actually generated. Therefore, although the Logos from which He was formed was eternal, the Son was not Himself eternal. For this reason, Servetus always rejected calling Christ the "eternal Son of God" but rather called him "the Son of the eternal God."

In describing Servetus' view of the Logos, Andrew Dibb explained: "In 'Genesis' God reveals himself as the creator. In 'John' he reveals that he created by means of the Word, or Logos. Finally, also in 'John', he shows that this Logos became flesh and 'dwelt among us'. Creation took place by the spoken word, for God said "Let there be ..." The spoken word of Genesis, the Logos of John, and the Christ, are all one and the same."

In his "Treatise Concerning the Divine Trinity" Servetus taught that the Logos was the reflection of Christ, and "That reflection of Christ was 'the Word with God" that consisted of God Himself, shining brightly in heaven, "and it was God Himself" and that "the Word was the very essence of God or the manifestation of God's essence, and there was in God no other substance or hypostasis than His Word, in a bright cloud where God then seemed to subsist. And in that very spot the face and personality of Christ shone bright."

Unitarian scholar Earl Morse Wilbur states, "Servetus' Errors of the Trinity is hardly heretical in intent, rather is suffused with passionate earnestness, warm piety, an ardent reverence for Scripture, and a love for Christ so mystical and overpowering that [he] can hardly find words to express it ... Servetus asserted that the Father, Son and Holy Spirit were dispositions of God, and not separate and distinct beings." Wilbur promotes the idea that Servetus was a modalist.

Servetus states his view clearly in the preamble to Restoration of Christianity (1553): "There is nothing greater, reader, than to recognize that God has been manifested as substance, and that His divine nature has been truly communicated. We shall clearly apprehend the manifestation of God through the Word and his communication through the Spirit, both of them substantially in Christ alone."

This theology, though original in some respects, has often been compared to Adoptionism, Arianism, and Sabellianism, all of which Trinitarians rejected in favour of the belief that God exists eternally in three distinct persons. Nevertheless, Servetus rejected these theologies in his books: Adoptionism, because it denied Jesus's divinity; Arianism, because it multiplied the hypostases and established a rank; and Sabellianism, because it seemingly confused the Father with the Son, though Servetus himself does appear to have denied or diminished the distinctions between the Persons of the Godhead, rejecting the Trinitarian understanding of One God in Three Persons.

Under severe pressure from Catholics and Protestants alike, Servetus clarified this explanation in his second book, Dialogues (1532), to show the Logos coterminous with Christ. He was nevertheless accused of heresy because of his insistence on denying the dogma of the Trinity and the distinctions between the three divine Persons in one God.

Legacy

Theology

Because of his rejection of the Trinity and eventual execution by burning for heresy, Unitarians often regard Servetus as the first (modern) Unitarian martyr—though he was a Unitarian in neither the 17th-century sense of the term nor the modern sense. Sharply critical though he was of the orthodox formulation of the trinity, Servetus is better described as a highly unorthodox trinitarian.

Aspects of his thinking—his critique of existing trinitarian theology, his devaluation of the doctrine of original sin, and his fresh examination of biblical proof-texts—did influence those who later inspired or founded unitarian churches in Poland and Transylvania.

Other non-trinitarian groups, such as Jehovah's Witnesses, and Oneness Pentecostalism, also claim Servetus held similar non-trinitarian views as theirs. Oneness Pentecostalism particularly identifies with Servetus' teaching on the divinity of Jesus Christ and his insistence on the oneness of God, rather than a Trinity of three distinct persons: "And because His Spirit was wholly God He is called God, just as from His flesh He is called man."

Oneness Pentecostal Scholar David K. Bernard has written the following in regard to the theology of Michael Servetus: "... some historians consider him to be a motivating force for the development of Unitarianism. However, he definitely was not Unitarian, for he acknowledged Jesus as God."

Swedenborg wrote a systematic theology that had many similarities to the theology of Servetus.

Freedom of conscience

Widespread aversion to Servetus's death has been taken as signaling the birth in Europe of the idea of religious tolerance, a principle now more important to modern Unitarian Universalists than antitrinitarianism. The Spanish scholar on Servetus' work, Ángel Alcalá, identified the radical search for truth and the right for freedom of conscience as Servetus' main legacies, rather than his theology. The Polish-American scholar, Marian Hillar, has studied the evolution of freedom of conscience, from Servetus and the Polish Socinians, to John Locke and to Thomas Jefferson and the American Declaration of Independence. According to Hillar: "Historically speaking, Servetus died so that freedom of conscience could become a civil right in modern society."

Science

Servetus was the first European to describe the function of pulmonary circulation although his achievement was not widely recognized at the time, for a few reasons. One was that the description appeared in a theological treatise, Christianismi Restitutio, not in a book on medicine. However, the sections in which he refers to anatomy and medicines demonstrate an amazing understanding of the body and treatments. Most copies of the book were burned shortly after its publication in 1553 because of persecution of Servetus by religious authorities. Three copies survived, but these remained hidden for decades. In passage V, Servetus recounts his discovery that the blood of the pulmonary circulation flows from the heart to the lungs (rather than air in the lungs flowing to the heart as had been thought). His discovery was based on the colour of the blood, the size and location of the different ventricles, and the fact that the pulmonary vein was extremely large, which suggested that it performed intensive and transcendent exchange. However, Servetus does not only deal with cardiology. In the same passage, from page 169 to 178, he also refers to the brain, the cerebellum, the meninges, the nerves, the eye, the tympanum, the rete mirabile, etc., demonstrating a great knowledge of anatomy. In some other sections of this work he also talks of medical products.

Servetus also contributed enormously to medicine with other published works specifically related to the field.

Honours

Geneva

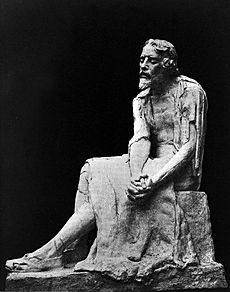

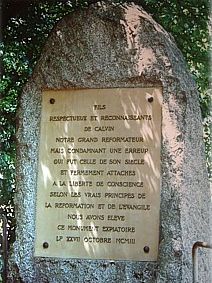

In Geneva, 350 years after the execution, remembering Servetus was still a controversial issue. In 1903 a committee was formed by supporters of Servetus to erect a monument in his honour. The group was led by a French Senator, Auguste Dide, an author of a book on heretics and revolutionaries which was published in 1887. The committee commissioned a local sculptor, Clotilde Roch, to execute a statue showing a suffering Servetus. The work was three years in the making and was finished in 1907. About the same time, a short street close by the stele was named after him. The city council then rejected the request of the committee to erect the completed statue, on the grounds that there was already a monument to Servetus.

In 1942, the Vichy Government took down the statue, as it was a celebration of freedom of conscience, and melted it. In 1960, having found the original molds, Annemasse had it recast and returned the statue to its previous place.

Finally, on 3 October 2011, Geneva erected a copy of the statue which it had rejected over 100 years before. It was cast in Aragon from the molds of Clotilde Roch's original statue. Rémy Pagani, former mayor of Geneva, inaugurated the statue. He previously had described Servetus as "the dissident of dissidence." Representatives from the Roman Catholic Church in Geneva and the Director of Geneva's International Museum of the Reformation attended the ceremony. A Geneva newspaper noted the absence of officials from the National Protestant Church of Geneva, the church of John Calvin.

Aragon

In 1984, the Zaragoza public hospital changed its name from José Antonio to Miguel Servet. Since 1999, this hospital has been known as the Hospital Universitario Miguel Servet, in recognition of its association with Servetus' own University of Zaragoza

See also

In Spanish: Miguel Servet para niños

In Spanish: Miguel Servet para niños