Nellie Bly facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Nellie Bly

|

|

|---|---|

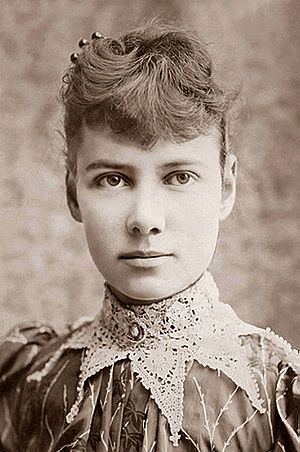

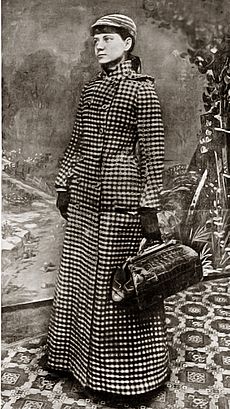

Elizabeth Cochran, "Nellie Bly", c. 1890

|

|

| Born |

Elizabeth Jane Cochran

May 5, 1864 Cochran's Mills, Pennsylvania, U.S.

|

| Died | January 27, 1922 (aged 57) New York City, New York, U.S.

|

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation | Journalist, novelist, inventor |

| Spouse(s) |

Robert Seaman

(m. 1895; died 1904) |

| Awards | National Women's Hall of Fame (1998) |

| Signature | |

|

|

Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman (born Elizabeth Jane Cochran; May 5, 1864 – January 27, 1922), better known by her pen name Nellie Bly, was an American journalist, industrialist, inventor, and charity worker who was widely known for her record-breaking trip around the world in 72 days, in emulation of Jules Verne's fictional character Phileas Fogg, and an exposé in which she worked undercover to report on a mental institution from within.

She was a pioneer in her field and launched a new kind of investigative journalism.

Contents

Early life

Elizabeth Jane Cochran was born May 5, 1864, in "Cochran's Mills", now part of the Pittsburgh suburb of Burrell Township, Armstrong County, Pennsylvania. Her father, Michael Cochran, born about 1810, started out as a laborer and mill worker before buying the local mill and most of the land surrounding his family farmhouse. He later became a merchant, postmaster, and associate justice at Cochran's Mills (which was named after him) in Pennsylvania. Michael married twice. He had 10 children with his first wife, Catherine Murphy, and 5 more children, including Elizabeth, with his second wife, Mary Jane Kennedy. Michael Cochran's father had immigrated from County Londonderry, Ireland, in the 1790s. He died in 1871, when Elizabeth was 6.

As a young girl, Elizabeth often was called "Pinky" because she so frequently wore that color. As she became a teenager, she wanted to portray herself as more sophisticated and so dropped the nickname and changed her surname to "Cochrane". In 1879, she enrolled at Indiana Normal School (now Indiana University of Pennsylvania) for one term but was forced to drop out due to lack of funds. In 1880, Cochrane's mother moved her family to Pittsburgh. A newspaper column entitled "What Girls Are Good For" in the Pittsburgh Dispatch that reported that girls were principally for birthing children and keeping house prompted Elizabeth to write a response under the pseudonym "Lonely Orphan Girl". The editor, George Madden, was impressed with her passion and ran an advertisement asking the author to identify herself. When Cochrane introduced herself to the editor, he offered her the opportunity to write a piece for the newspaper, again under the pseudonym "Lonely Orphan Girl". Her first article for the Dispatch, entitled "The Girl Puzzle", was about how divorce affected women. In it, she argued for reform of divorce laws. Madden was impressed again and offered her a full-time job. It was customary for women who were newspaper writers at that time to use pen names. The editor chose "Nellie Bly", after the African-American title character in the popular song "Nelly Bly" by Stephen Foster. Cochrane originally intended that her pseudonym be "Nelly Bly", but her editor wrote "Nellie" by mistake, and the error stuck.

Career

Pittsburgh Dispatch

As a writer, Nellie Bly focused her early work for the Pittsburgh Dispatch on the lives of working women, writing a series of investigative articles on women factory workers. However, the newspaper soon received complaints from factory owners about her writing, and she was reassigned to women's pages to cover fashion, society, and gardening, the usual role for women journalists, and she became dissatisfied. Still only 21, she was determined "to do something no girl has done before." She then traveled to Mexico to serve as a foreign correspondent, spending nearly half a year reporting on the lives and customs of the Mexican people; her dispatches later were published in book form as Six Months in Mexico. In one report, she protested the imprisonment of a local journalist for criticizing the Mexican government, then a dictatorship under Porfirio Díaz. When Mexican authorities learned of Bly's report, they threatened her with arrest, prompting her to flee the country. Safely home, she accused Díaz of being a tyrannical czar suppressing the Mexican people and controlling the press.

Asylum exposé

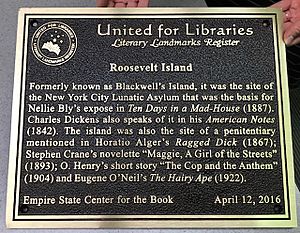

Burdened again with theater and arts reporting, Bly left the Pittsburgh Dispatch in 1887 for New York City. Penniless after four months, she talked her way into the offices of Joseph Pulitzer's newspaper the New York World and took an undercover assignment for which she agreed to feign insanity to investigate reports of brutality and neglect at the Women's Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell's Island.

It was not an easy task for Bly to be admitted to the Asylum: she first decided to check herself into a boarding house called Temporary Homes for Females. She stayed up all night to give herself the wide-eyed look of a disturbed woman and began making accusations that the other boarders were insane. Bly told the assistant matron: "There are so many crazy people about, and one can never tell what they will do." She refused to go to bed and eventually scared so many of the other boarders that the police were called to take her to the nearby courthouse. Once examined by a police officer, a judge, and a doctor, Bly was taken to Blackwell's Island.

Committed to the asylum, Bly experienced the deplorable conditions firsthand. After ten days, the asylum released Bly at The World's behest. Her report, later published in book form as Ten Days in a Mad-House, caused a sensation, prompted the asylum to implement reforms, and brought her lasting fame.

Around the world and general impact

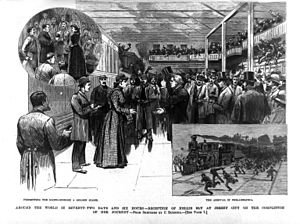

In 1888, Bly suggested to her editor at the New York World that she take a trip around the world, attempting to turn the fictional Around the World in Eighty Days (1873) into fact for the first time. A year later, at 9:40 a.m. on November 14, 1889, and with two days' notice, she boarded the Augusta Victoria, a steamer of the Hamburg America Line, and began her 40,070 kilometer journey. She took with her the dress she was wearing, a sturdy overcoat, several changes of underwear, and a small travel bag carrying her toiletry essentials. She carried most of her money (£200 in English bank notes and gold, as well as some American currency) in a bag tied around her neck.

The New York newspaper Cosmopolitan sponsored its own reporter, Elizabeth Bisland, to beat the time of both Phileas Fogg and Bly. Bisland would travel the opposite way around the world, starting on the same day as Bly took off. Bly, however, did not learn of Bisland's journey until reaching Hong Kong. She dismissed the cheap competition. "I would not race," she said. "If someone else wants to do the trip in less time, that is their concern."

To sustain interest in the story, the World organized a "Nellie Bly Guessing Match" in which readers were asked to estimate Bly's arrival time to the second, with the Grand Prize consisting at first of a free trip to Europe and, later on, spending money for the trip.

During her travels around the world, Bly went through England, France (where she met Jules Verne in Amiens), Brindisi, the Suez Canal, Colombo (Ceylon), the Straits Settlements of Penang and Singapore, Hong Kong, and Japan. The development of efficient submarine cable networks and the electric telegraph allowed Bly to send short progress reports, although longer dispatches had to travel by regular post and thus were often delayed by several weeks.

Bly traveled using steamships and the existing railroad systems, which caused occasional setbacks, particularly on the Asian leg of her race. During these stops, she visited a leper colony in China and, in Singapore, she bought a monkey.

As a result of rough weather on her Pacific crossing, she arrived in San Francisco on the White Star Line ship RMS Oceanic on January 21, two days behind schedule. However, after World owner Pulitzer chartered a private train to bring her home, she arrived back in New Jersey on January 25, 1890, at 3:51 pm.

Just over seventy-two days after her departure from Hoboken, Bly was back in New York. She had circumnavigated the globe, traveling alone for almost the entire journey. Bisland was, at the time, still crossing the Atlantic, only to arrive in New York four and a half days later. She also had missed a connection and had to board a slow, old ship (the Bothnia) in the place of a fast ship (Etruria). Bly's journey was a world record, although it was bettered a few months later by George Francis Train, whose first circumnavigation in 1870 possibly had been the inspiration for Verne's novel. Train completed the journey in 67 days, and on his third trip in 1892 in 60 days. By 1913, Andre Jaeger-Schmidt, Henry Frederick, and John Henry Mears had improved on the record, the latter completing the journey in fewer than 36 days.

Later work

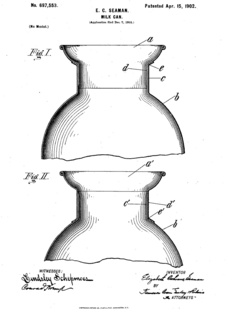

In 1895, Bly married millionaire manufacturer Robert Seaman. Bly was 31 and Seaman was 73 when they married. Due to her husband's failing health, she left journalism and succeeded her husband as head of the Iron Clad Manufacturing Co., which made steel containers such as milk cans and boilers. In 1904, Seaman died.

In 1904, Iron Clad began manufacturing the steel barrel that was the model for the 55-gallon oil drum still in widespread use in the United States. There have been claims that Bly invented the barrel. The inventor was registered as Henry Wehrhahn (U.S. Patents 808,327 and 808,413).

Bly was, however, an inventor in her own right, receiving U.S. Patent 697,553 for a novel milk can and U.S. Patent 703,711 for a stacking garbage can, both under her married name of Elizabeth Cochrane Seaman. For a time she was one of the leading women industrialists in the United States, but her negligence and embezzlement by a factory manager resulted in the Iron Clad Manufacturing Co. going bankrupt.

Back in reporting, she wrote stories on Europe's Eastern Front during World War I. Bly was the first woman and one of the first foreigners to visit the war zone between Serbia and Austria. She was arrested when she was mistaken for a British spy.

Bly covered the Woman Suffrage Procession of 1913. Under the headline "Suffragists Are Men's Superiors", her parade story predicted that it would be 1920 before women in the United States would be given the right to vote.

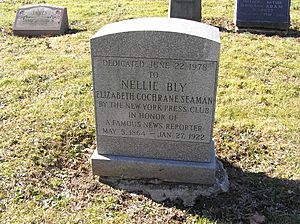

Death

On January 27, 1922, Bly died of pneumonia at St. Mark's Hospital, New York City, aged 57. She was interred at Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City.

Legacy

Honors

In 1998, Bly was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame. Bly was one of four journalists honored with a US postage stamp in a "Women in Journalism" set in 2002.

The New York Press Club confers an annual Nellie Bly Cub Reporter journalism award to acknowledge the best journalistic effort by an individual with three years or less professional experience.

Theater

Bly was the subject of the 1946 Broadway musical Nellie Bly by Johnny Burke and Jimmy Van Heusen. The show ran for 16 performances.

During the 1990s, playwright Lynn Schrichte wrote and toured Did You Lie, Nellie Bly?, a one-woman show about Bly.

Film and television

A fictionalized version of Bly as a mouse named Nellie Brie appears as a central character in the animated children's film An American Tail: The Mystery of the Night Monster.

On May 5, 2015, the Google search engine produced an interactive "Google Doodle" for Bly; for the "Google Doodle" Karen O wrote, composed, and recorded an original song about Bly, and Katy Wu created an animation set to Karen O's music.

Literature

Bly has been featured as the protagonist of novels by David Blixt, Marshall Goldberg, Dan Jorgensen, Carol McCleary, Pearry Reginald Teo and Christine Converse.

A fictionalized account of Bly's around the world trip was used in the 2010 comic book Julie Walker Is The Phantom published by Moonstone Books (Story: Elizabeth Massie, art: Paul Daly, colors: Stephen Downer).

Bly is one of 100 women featured in the first version of the book Good Night Stories for Rebel Girls written by Elena Favilli & Francesca Cavallo.

Eponyms and namesakes

The board game Round the World with Nellie Bly created in 1890 is named in recognition of her trip.

The Nellie Bly Amusement Park in Brooklyn, New York City, was named after her, taking as its theme Around the World in Eighty Days. The park reopened in 2007 under new management, renamed "Adventurers Amusement Park".

A fireboat named Nellie Bly operated in Toronto, Canada in the first decade of the 20th Century.

From early in the twentieth century until 1961, the Pennsylvania Railroad operated an express train between New York and Atlantic City named Nellie Bly. In its early years it was a parlor-car only train. The train's route bypassed Philadelphia for a shorter trip.

Images for kids

-

A steam tug named after Bly served as a fireboat in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

See also

In Spanish: Nellie Bly para niños

In Spanish: Nellie Bly para niños