Peace Conference of 1861 facts for kids

The Peace Conference of 1861 was a meeting of 131 leading American politicians in February 1861, at the Willard's Hotel in Washington, D.C., on the eve of the American Civil War. The purpose of the conference was to avoid, if possible, the secession of the eight slave states, from the upper and border South, that had not done so as of that date. The seven states that had already seceded did not attend.

Contents

Background

Republican President Abraham Lincoln's election in 1860, led many in the South to conclude that now was the time for their long-discussed secession. Many pro-slavery southerners, especially in the Lower South, were convinced—incorrectly—that the new Republican government was determined to abolish slavery where it already existed, and that the abolitionist John Brown was the North's hero. (In fact, Republicans only wished to restrict slavery's expansion into federally-held western territories, and most northerners—Republicans and Democrats alike—disavowed and indeed abhorred John Brown and his tactics.)

In much of the South, elections were held to select delegates to special conventions to consider secession from the Union. In Congress, efforts were made in both the House of Representatives and the Senate to reach compromise over the issues relating to slavery that were dividing the nation.

Four proposals to preserve the Union

First Crittenden proposal: six constitutional amendments

In December 1860, the final session of the Thirty-sixth Congress met. In the House, the Committee of Thirty-Three, with one member from each state, led by Ohio Republican Thomas Corwin, was formed to reach a compromise to preserve the Union. In the Senate, former Kentucky Whig John J. Crittenden, elected as a Unionist candidate, submitted the Crittenden Compromise, six proposed constitutional amendments that he hoped would address all the outstanding issues. Hopes were high, especially in the border states, that the lame duck Congress could reach a successful resolution before the new Republican administration took office.

Crittenden's proposals were debated by a specially-selected Committee of Thirteen. The proposals provided for, among other things, an extension of the Missouri Compromise line dividing the territories to the Pacific Ocean, bringing his efforts directly in conflict with the 1860 Republican Platform and the personal views of President-elect Abraham Lincoln, who had made known his objections. The compromise was rejected by the committee on December 22 by a vote of 7–6. Crittenden later brought the issue to the floor of the Senate as a proposal to have his compromise made subject to a national referendum, but the Senate rejected it on January 16, by a vote of 25–23.

Second Crittenden proposal

A modified version of the Crittenden Plan, believed to be more attractive to Republicans, was considered by an ad hoc committee of 14 congressmen from the lower North and the upper South, meeting several times between December 28 and January 4. The committee was chaired again by Crittenden and included other Southern Unionists such as Representatives John A. Gilmer of North Carolina, Robert H. Hatton of Tennessee, J. Morrison Harris of Maryland, and John T. Harris of Virginia. A version of their work was rejected by the House on January 7.

Constitutional amendment protecting slavery

In the House, on January 14 the Committee of Thirty-Three reported that it had reached majority agreement on a constitutional amendment to protect slavery where it existed, and the immediate admission of New Mexico Territory as a slave state. This latter proposal would result in a de facto extension of the Missouri Compromise line for all existing territories.

Proposal from Virginia to hold a peace conference

A fourth attempt came from the state of Virginia, one of the slave states that had not yet seceded. Former President John Tyler, a private citizen of Virginia who was still much interested in the fate of the nation, had been appointed as a special Virginia envoy to President James Buchanan to urge him to maintain the status quo in regard to the seceded states. Later, Tyler was an elected delegate to the Virginia convention called to consider whether or not to follow the Deep South states out of the Union. Tyler thought that a final collective effort should be made to preserve the Union and in a document published on January 17, 1861, he called for a convention of the six free and six slave border states to resolve the sectional split. Governor John Letcher of Virginia had already made a similar request to the state legislature, agreed to sponsor the convention while the list of attendees to all of the states was expanded. Corwin agreed to hold off any final vote on his House plan pending the final actions of the peace conference.

The peace conference

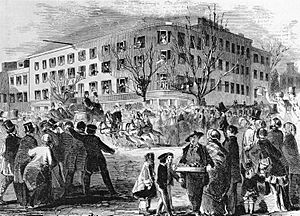

The conference convened on February 4, 1861, at the Willard Hotel in Washington, D.C.; all seven Deep South states (Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, South Carolina, Texas) had already passed ordinances of secession, were preparing to form a new government in Montgomery, Alabama, and did not attend the peace conference, not believing it would accomplish anything significant. At the same time that Tyler, selected to head the convention, was making his opening remarks in Washington, his granddaughter was ceremonially hoisting the flag for the Confederate convention in Montgomery. No delegates were sent by the Deep South states or by Arkansas, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, California, or Oregon. Fourteen free states and seven slave states (Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, Missouri, North Carolina, Tennessee, and Virginia) were represented. Among the representatives to the conference were James A. Seddon and William Cabell Rives from Virginia, David Wilmot from Pennsylvania, Francis Granger from New York, Reverdy Johnson from Maryland, William P. Fessenden and Lot M. Morrill from Maine, James Guthrie and William O. Butler from Kentucky, Stephen T. Logan from Illinois, Alvan Cullom from Tennessee, and Thomas Ewing and Salmon P. Chase from Ohio. Many of the delegates came in the belief that they could be successful, but many others, from both sides of the spectrum, came simply as "watchdogs" for their sectional interests. The 131 delegates included "six former cabinet members, nineteen ex-governors, fourteen former senators, fifty former representatives, twelve state supreme court justices, and one former president", and the meeting was frequently referred to derisively as the Old Gentleman's Convention.

On February 6 a committee, charged with drafting a proposal for the entire convention to consider, was formed. The committee consisted of one representative from each state, and was headed by James Guthrie. The entire convention met for three weeks, and its final product was a proposed seven-point constitutional amendment that differed little from the Crittenden Compromise. The key issue, slavery in the territories, was addressed simply by extending the Missouri Compromise line to the Pacific Ocean, with no provision for newly acquired territory. That section passed by a 9–8 vote of the states, each state with one vote.

Other features of the proposed constitutional amendment were the requirement for the acquisition of all future territories to be approved by a majority of both the slave states and the free states, a prohibition on Congress passing any legislation that would affect the status of slavery where it currently existed, a prohibition on state legislatures from passing laws that would restrict the ability of officials to apprehend and return fugitive slaves, a permanent prohibition on the foreign slave trade, and 100% compensation to any master whose fugitive slave was freed by illegal mob action or intimidation of officials required to administer the Fugitive Slave Act. Key sections of this amendment could be further amended only with the unanimous concurrence of all of the states.

Aftermath

Since it did not pledge to limit the expansion of slavery in new territories, the compromise failed to satisfy most Republicans. In not pledging to permit and protect slavery in the territories, the compromise failed to address the issue that had divided the Democratic Party into Northern and Southern factions in the 1860 presidential elections. The convention's work was completed with only a few days left in the final session of Congress. The proposal was rejected in the Senate in a 28–7 vote and never came to a vote in the House. The Corwin Amendment, a less-encompassing constitutional amendment that was finally submitted by the Committee of Thirty-Three was passed by Congress, but it simply provided protection for slavery where it currently existed, something that Lincoln and most members of both parties already believed was a state right protected by the existing US Constitution. A bill for New Mexico statehood was tabled by a vote of 115–71 with opposition coming from both Southern Democrats as well as Republicans.

With the adjournment of Congress and the inauguration of Lincoln as president, the only avenue for compromise involved informal negotiations between Unionist Southerners and representatives of the incoming Republican government: Congress was no longer a factor. A final convention of only the slave states still in the Union scheduled for June 1861 never occurred because of the events at Fort Sumter. Robert H. Hatton, a Unionist from Tennessee who would later change sides, summed up the feelings of many shortly before Congress adjourned:

- We are getting along badly with our work of compromise – badly. We will break, I apprehend, without any thing being done. God will hold some men to a fearful responsibility. My heart is sick.