Peninsular War facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Peninsular War |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Napoleonic Wars | |||||||

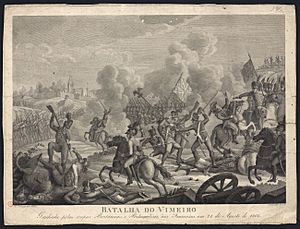

Clockwise from top left:

Dos de Mayo Uprising/Battle of Somosierra/Battle of Bayonne/Disasters of War prints by Goya |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

|||||||

| 1,000,000+ military and civilian dead | |||||||

The Peninsular War (1807–1814) was a war between the first French Empire and the Spanish Empire for control of what is now Spain and Portugal. The war began when French and Spanish armies invaded and occupied Portugal in 1807. It became more serious in 1808 when France attacked Portugal's ally Spain, and made Joseph Bonaparte its king. General Sir Arthur Wellesley, later Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, became famous in the war. The war lasted until certain European states joined together in the Sixth Coalition and defeated Napoleon in 1814.

Contents

Extortion of Portugal

The Treaties of Tilsit, negotiated during a meeting in July 1807 between Emperors Alexander I of Russia and Napoleon, concluded the War of the Fourth Coalition. With Prussia shattered, and the Russian Empire allied with the First French Empire, Napoleon expressed irritation that Portugal was open to trade with Britain. When Portugal refused to follow Napoleon's orders demanding that it declared war on Britain, Napoleon ordered his troops to march on Lisbon.

The secret Treaty of Fontainebleau signed between France and Spain proposed to carve up Portugal into three entities. Porto and the northern part was to become the Kingdom of Northern Lusitania, under Charles II, Duke of Parma. The southern portion, as the Principality of the Algarves, would fall to Godoy. The rump of the country, centered on Lisbon, was to be administered by the French. According to the Treaty of Fontainebleau, Napoleon's invasion force was to be supported by 25,500 Spanish troops. On 12 October, Junot's corps began crossing the Bidasoa River into Spain at Irun. Junot was selected because he had served as ambassador to Portugal in 1805. He was known as a good fighter and an active officer, although he had never exercised independent command.

Invasion of Portugal

Napoleon instructed Junot, with the cooperation of Spanish military troops, to invade Portugal, moving west from Alcántara along the Tagus valley to Portugal, a distance of only 120 miles (193 km). On 19 November 1807, the French Troops under Junot set out for Lisbon and occupied it on 30 November.

The Prince Regent John escaped, loading his family, courtiers, state papers and treasure aboard the fleet, protected by the British, and fled to Brazil. He was joined in flight by many nobles, merchants and others. With 15 warships and more than 20 transports, the fleet of refugees weighed anchor on 29 November and set sail for the colony of Brazil. The flight had been so chaotic that 14 carts loaded with treasure were left behind on the docks.

As one of Junot's first acts, the property of those who had fled to Brazil was sequestered and a 100-million-franc indemnity imposed. The army formed into a Portuguese Legion, and went to northern Germany to perform garrison duty. Junot did his best to calm the situation by trying to keep his troops under control. While the Portuguese authorities were generally subservient toward their French occupiers, the ordinary Portuguese were angry, and the harsh taxes caused bitter resentment among the population. By January 1808, there were executions of persons who resisted the exactions of the French. The situation was dangerous, but it would need a trigger from outside to transform unrest into revolt.

Coup d'état

Between 9 and 12 February, the French divisions of the eastern and western Pyrenees crossed the border and occupied Navarre and Catalonia, including the citadels of Pamplona and Barcelona. The Spanish government demanded explanations from their French allies, but these did not satisfy and in response Godoy pulled Spanish troops out of Portugal. Since Spanish fortress commanders had not received instructions from the central government, they were unsure how to treat the French troops, who marched openly as allies with flags flying and bands announcing their arrival. Some commanders opened their fortresses to them, while others resisted.

On 20 February, Joachim Murat was appointed lieutenant of the emperor and commander of all French troops in Spain, which now numbered 60,000–100,000. On 24 February, Napoleon declared that he no longer considered himself bound by the Treaty of Fontainebleau. In early March, Murat established his headquarters in Vitoria and received 6,000 reinforcements from the Imperial Guard.

On 19 March 1808, Godoy fell from power in the Mutiny of Aranjuez and Charles IV was forced to abdicate in favour of his son, Ferdinand VII. In the aftermath of the abdication, attacks on godoyistas were frequent. On 23 March, Murat entered Madrid with pomp. Ferdinand VII arrived on 27 March and asked Murat to get Napoleon's confirmation of his accession. Charles IV, however, was persuaded to protest his abdication to Napoleon, who summoned the royal family, both kings included, to Bayonne in France. There on 5 May, under French pressure, the two kings both abdicated their claims to Napoleon. Napoleon then had the Junta de Gobierno—the council of regency in Madrid—formally ask him to appoint his brother Joseph as King of Spain. The abdication of Ferdinand was only publicised on 20 May.

Iberia in revolt

On 2 May, the citizens of Madrid rebelled against the French occupation; the uprising was put down by Joachim Murat's elite Imperial Guard and Mamluk cavalry, which crashed into the city and trampled the rioters . In addition, the Mamelukes of the Imperial Guard of Napoleon fought residents of Madrid, wearing turbans and using curved scimitars, thus provoking memories of the Muslim Spain. The next day, as immortalized by Francisco Goya in his painting The Third of May 1808, the French army shot hundreds of Madrid's citizens. Similar reprisals occurred in other cities and continued for days. Bloody, spontaneous fighting known as guerrilla (literally "little war") broke out in much of Spain against the French as well as the Ancien Régime's officials. Although the Spanish government, including the Council of Castile, had accepted Napoleon's decision to grant the Spanish crown to his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, the Spanish population rejected Napoleon's plans. The first wave of uprisings were in Cartagena and Valencia on 23 May; Zaragoza and Murcia on 24 May; and the province of Asturias, which cast out its French governor on 25 May and declared war on Napoleon. Within weeks, all the Spanish provinces followed suit. After hearing of the Spanish uprising, Portugal erupted in revolt in June. A French detachment under Louis Henri Loison crushed the rebels at Évora on 29 July and massacred the town's population.

The deteriorating strategic situation led France to increase its military commitments. By 1 June, over 65,000 troops were rushing into the country to control the crisis. The main French army of 80,000 held a narrow strip of central Spain from Pamplona and San Sebastián in the north to Madrid and Toledo in the centre. The French in Madrid sheltered behind an additional 30,000 troops under Marshal Bon-Adrien Jeannot de Moncey. Jean-Andoche Junot's corps in Portugal was cut off by 300 miles (480 km) of hostile territory, but within days of the outbreak of revolt, French columns in Old Castile, New Castile, Aragon and Catalonia were searching for the insurgent forces.

In 1808, the Spanish Army in Andalusia defeated the French in the Battle of Bailen, considered the first open-field defeat of the Napoleonic army in European battlefields. Besieged by 70,000 French troops, a reconstituted national government, the Cortes of Cádiz—in effect a government-in-exile—fortified itself in the secure port of Cádiz in 1810.

British intervention

In August 1808, 15,000 British troops—including the King's German Legion—landed in Portugal under the command of Lieutenant-General Sir Arthur Wellesley. The British guarded Portugal and campaigned against the French alongside the reformed Portuguese army and provided whatever supplies they could get to the Spanish, while the Spanish armies and guerrillas tied down vast numbers of Napoleon's troops.

End of war

In 1812, when Napoleon set out with a massive army on what proved to be a disastrous French invasion of Russia, a combined allied army defeated the French at Salamanca and took the capital Madrid. In the following year the Coalition scored a victory over King Joseph Bonaparte's army in the Battle of Vitoria paving the victory of the war in the Iberian Peninsula.

Pursued by the armies of Spain, Portugal and Britain, Marshal Jean-de-Dieu Soult, no longer getting sufficient support from a depleted France, led the exhausted and demoralized French forces in a fighting withdrawal across the Pyrenees during the winter of 1813–1814. The years of fighting in Spain were a heavy burden on France's Grande Armée. While the French enjoyed several victories in battle, they were eventually defeated, as their communications and supplies were severely tested and their units were frequently isolated, harassed or overwhelmed by Spanish partisans fighting an intense guerrilla war of raids and ambushes. The Spanish armies were repeatedly beaten and driven to the peripheries, but they would regroup and relentlessly hound and demoralize the French troops. This drain on French resources led Napoleon, who had unwittingly provoked a total war, to call the conflict the "Spanish Ulcer".

War and revolution against Napoleon's occupation led to the Spanish Constitution of 1812, promulgated by the Cortes of Cádiz, later a cornerstone of European liberalism. The burden of war destroyed the social and economic fabric of Portugal and Spain; and the following civil wars between liberal and absolutist factions ushered revolts in Latin America and the beginning of an era of social turbulence, increased political instability, and economic stagnation.

On 13 April 1814 the abdication of Napoleon was announced. The Peace of Paris was formally signed at Paris on 30 May 1814.

Aftermath

Ferdinand VII remained King of Spain having been acknowledged on 11 December 1813 by Napoleon in the Treaty of Valençay. The remaining afrancesados were exiled to France. The whole country had been pillaged by Napoleon's troops. The Catholic Church had been ruined by its losses and society subjected to destabilizing change.

With Napoleon exiled to the island of Elba, Louis XVIII was restored to the French throne.

British troops were partly sent to England, and partly embarked at Bordeaux for America for service in the final months of the American War of 1812.

After the Peninsular War, the pro-independence traditionalists and liberals clashed in the Carlist Wars, as King Ferdinand VII ("the Desired One"; later "the Traitor King") revoked all the changes made by the independent Cortes Generales in Cádiz, the Constitution of 1812 on 4 May 1814. Military officers forced Ferdinand to accept the Cádiz Constitution again in 1820, and was in effect until April 1823, during what is known as the Trienio Liberal.

The experience in self-government led the later Libertadores (Liberators) to promote the independence of Spanish America.

Portugal's position was more favorable than Spain's. Revolt had not spread to Brazil, there was no colonial struggle and there had been no attempt at political revolution. The Portuguese Court's transfer to Rio de Janeiro initiated the independence of Brazil in 1822.

The war against Napoleon remains as the bloodiest event in Spain's modern history.

Images for kids

-

Joaquín Sorolla: The death of Pedro Velarde y Santillán during the defence of the Monteleon Artillery Barracks

-

Joaquín Sorolla: Valencians prepare to resist the invaders (1884)

-

The Spanish Army's triumph at Bailén was the French Empire's first land defeat. Painting by José Casado del Alisal

-

Marshal Jean-de-Dieu Soult at the First Battle of Porto by Joseph Beaume

-

The Proclamation of the Constitution of 1812 by Salvador Viniegra

-

Silver coin: 1000 reis Manuel II of Portugal, 1910 - commemorating the Peninsular War

-

British infantry attempt to scale the walls of Badajoz, 1812

-

Thomas Lawrence: Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington.

-

Battle of the Pyrenees, 25 July 1813

-

The Battle of the Bidassoa, 1813

-

French victories of the Peninsular War inscribed on the Arc de Triomphe

-

Statue of Juana Galán in Valdepeñas, by sculptor Francisco Javier Galán

See also

In Spanish: Guerra de la Independencia Española para niños

In Spanish: Guerra de la Independencia Española para niños