Pontius Pilate facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Pontius Pilate

|

|

|---|---|

| Pontius Pilatus | |

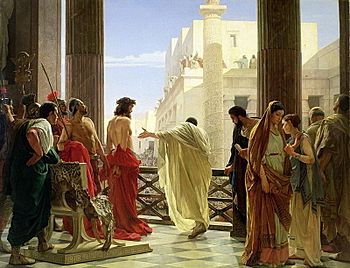

Ecce Homo ("Behold the Man"), Antonio Ciseri's depiction of Pilate presenting a scourged Jesus to the people of Jerusalem

|

|

| 5th Prefect of Judaea | |

| In office c. 26 AD – 36 AD |

|

| Appointed by | Tiberius |

| Preceded by | Valerius Gratus |

| Succeeded by | Marcellus |

| Personal details | |

| Nationality | Roman |

| Spouse | Unknown |

| Known for | Pilate's court |

Pontius Pilate (Latin: Pontius Pilatus; Greek: Πόντιος Πιλᾶτος, Pontios Pilatos) was the fifth governor of the Roman province of Judaea, serving under Emperor Tiberius from 26/27 to 36/37 AD. He is best known for being the official who presided over the trial of Jesus and ultimately ordered his crucifixion.

Contents

Early life

The sources give no indication of Pilate's life prior to his becoming governor of Judaea. His praenomen (first name) is unknown; his cognomen Pilatus might mean "skilled with the javelin (pilum)," but it could also refer to the pileus or Phrygian cap, possibly indicating that one of Pilate's ancestors was a freedman. If it means "skilled with the javelin," it is possible that Pilate won the cognomen for himself while serving in the Roman military; it is also possible that his father acquired the cognomen through military skill.

Pilate was likely educated, somewhat wealthy, and well-connected politically and socially. He was probably married, but the only extant reference to his wife, in which she tells him not to interact with Jesus after she has had a disturbing dream (Matthew 27:19), is generally dismissed as legendary. According to the cursus honorum established by Augustus for office holders of equestrian rank, Pilate would have had a military command before becoming prefect of Judaea; Alexander Demandt speculates that this could have been with a legion stationed at the Rhine or Danube. Although it is therefore likely Pilate served in the military, it is nevertheless not certain.

Role as governor of Judaea

Pilate is the best-attested governor of Judaea, few sources regarding his rule have survived. Nothing is known about his life before he became governor of Judaea, and nothing is known about the circumstances that led to his appointment to the governorship.

Pilate was the fifth governor of the Roman province of Judaea, during the reign of the emperor Tiberius. The post of governor of Judaea was of relatively low prestige and nothing is known of how Pilate obtained the office. Josephus states that Pilate governed for 10 years (Antiquities of the Jews 18.4.2), and these are traditionally dated from 26 to 36/37, making him one of the two longest-serving governors of the province.

As governor, Pilate had the right to appoint the Jewish High Priest and also officially controlled the vestments of the High Priest in the Antonia Fortress. Unlike his predecessor, Valerius Gratus, Pilate retained the same high priest, Joseph ben Caiaphas, for his entire tenure. Caiaphas would be removed following Pilate's own removal from the governorship. This indicates that Caiaphas and the priests of the Sadducee sect were reliable allies to Pilate.

In the Gospels

At the Passover of most likely 30 or 33, Pontius Pilate condemned Jesus of Nazareth to death by crucifixion in Jerusalem. The main sources on the crucifixion are the four canonical Christian Gospels, the accounts of which vary.

Pilate's role in condemning Jesus to death is also attested by the Roman historian Tacitus.

It is generally assumed, based on the unanimous testimony of the gospels, that the crime for which Jesus was brought to Pilate and executed was sedition, founded on his claim to be king of the Jews. Pilate may have judged Jesus according to the cognitio extra ordinem, a form of trial for capital punishment used in the Roman provinces and applied to non-Roman citizens that provided the prefect with greater flexibility in handling the case. All four gospels also mention that Pilate had the custom of releasing one captive in honor of the Passover festival; this custom is not attested in any other source.

In the Gospels, Pilate is portrayed as reluctant to execute Jesus and pressured to do so by the crowd and Jewish authorities. Some scholars argue that Pilate's hesitation was due to the fear of causing a revolt during Passover, when large numbers of pilgrims were in Jerusalem.

Removal and later life

Pilate's removal as governor occurred after Pilate slaughtered a group of armed Samaritans at a village called Tirathana near Mount Gerizim, where they hoped to find artifacts that had been buried there by Moses. The Samaritans, claiming not to have been armed, complained to Lucius Vitellius the Elder, the governor of Syria (term 35–39), who had Pilate recalled to Rome to be judged by Tiberius. Tiberius, however, had died before his arrival. This dates the end of Pilate's governorship to 36/37. Tiberius died in Misenum on the 16th of March in 37, in his seventy-eighth year.

Following Tiberius's death, Pilate's hearing would have been handled by the new emperor Caligula: it is unclear whether any hearing took place, as new emperors often dismissed outstanding legal matters from previous reigns. The only sure outcome of Pilate's return to Rome is that he was not reinstated as governor of Judaea, either because the hearing went badly, or because Pilate did not wish to return. J. P. Lémonon argues that the fact that Pilate was not reinstated by Caligula does not mean that his trial went badly, but may simply have been because after ten years in the position it was time for him to take a new posting. Joan Taylor, on the other hand, argues that Pilate seems to have ended his career in disgrace.

The church historian Eusebius (Church History 2.7.1), writing in the early fourth century, claims that "tradition relates that" Pilate took his own life after he was recalled to Rome due to the disgrace he was in. Eusebius dates this to 39. The Christian apologist Origen, writing c. 248 AD, argued that nothing bad happened to Pilate, because the Jews and not Pilate were responsible for Jesus' death; he therefore also assumed that Pilate did not die a shameful death.

In legends

Due to his role in Jesus' trial, Pilate became an important figure in both pagan and Christian propaganda in late antiquity.

Positive traditions about Pilate are frequent in Eastern Christianity, particularly in Egypt and Ethiopia, whereas negative traditions predominate in Western and Byzantine Christianity. Additionally, earlier Christian traditions portray Pilate more positively than later ones, a change which Ann Wroe suggests reflects the fact that, following the legalization of Christianity in the Roman Empire by the Edict of Milan (312), it was no longer necessary to deflect criticism of Pilate (and by extension of the Roman Empire) for his role in Jesus's crucifixion onto the Jews. Bart Ehrman, on the other hand, argues that the tendency in the Early Church to exonerate Pilate and blame the Jews prior to this time reflects an increasing "anti-Judaism" among Early Christians. The earliest attestation of a positive tradition about Pilate comes from the late first-, early second-century Christian author Tertullian, who, claiming to have seen Pilate's report to Tiberius, states Pilate had "become already a Christian in his conscience." An earlier reference to Pilate's records of Jesus's trial is given by the Christian apologist Justin Martyr around 160. Tibor Grüll believes that this could be a reference to Pilate's actual records, but other scholars argue that Justin has simply invented the records as a source on the assumption that they existed without ever having verified their existence.

In culture

Pilate has frequently been a subject of artistic representation. Medieval art frequently portrayed scenes of Pilate and Jesus, often in the scene where he washes his hands of guilt for Jesus's death. In the art of the Late Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Pilate is often depicted as a Jew. The nineteenth century saw a renewed interest in depicting Pilate, with numerous images made. He plays an important role in medieval passion plays, where he is often a more prominent character than Jesus. His characterization in these plays varies greatly, from weak-willed and coerced into crucifying Jesus to being an evil person who demands Jesus's crucifixion. Modern authors who feature Pilate prominently in their works include Anatole France, Mikhail Bulgakov, and Chingiz Aitmatov, with a majority of modern treatments of Pilate dating to after the Second World War. Pilate has also frequently been portrayed in film.

Film

Pilate has been depicted in a number of films, being included in portrayals of Christ's passion already in some of the earliest films produced. In the 1927 silent film The King of Kings, Pilate is played by Hungarian-American actor Victor Varconi, who is introduced seated under an enormous 37 feet high Roman eagle, which Christopher McDonough argues symbolizes "not power that he possesses but power that possesses him". During the Ecce homo scene, the eagle stands in the background between Jesus and Pilate, with a wing above each figure; after hesitantly condemning Jesus, Pilate passes back to the eagle, which is now framed beside him, showing his isolation in his decision and, McDonough suggests, causing the audience to question how well he has served the emperor.

The film The Last Days of Pompeii (1935) portrays Pilate as "a representative of the gross materialism of the Roman empire", with the actor Basil Rathbone giving him long fingers and a long nose. Following the Second World War, Pilate and the Romans often take on a villainous role in American film. The 1953 film The Robe portrays Pilate as completely covered with gold and rings as a sign of Roman decadence. The 1959 film Ben-Hur shows Pilate (the Australian actor, Frank Thring, Jr.) presiding over a chariot race, in a scene that Ann Wroe says "seemed closely modeled on the Hitler footage of the 1936 Olympics," with Pilate bored and sneering. Martin Winkler, however, argues that Ben-Hur provides a more nuanced and less condemnatory portrayal of Pilate and the Roman Empire than most American films of the period.

Only one film has been made entirely in Pilate's perspective, the 1962 French-Italian Ponzio Pilato, where Pilate was played by Jean Marais. In the 1973 film Jesus Christ Superstar, based on the 1970 rock opera, the trial of Jesus takes place in the ruins of a Roman theater, suggesting the collapse of Roman authority and "the collapse of all authority, political or otherwise". The Pilate in the film, played by Barry Dennen, expands on John 18:38 to question Jesus on the truth and appears, in McDonough's view, as "an anxious representative of [...] moral relativism". Speaking of Dennen's portrayal in the trial scene, McDonough describes him as a "cornered animal." Wroe argues that later Pilates took on a sort of effeminancy, illustrated by Michael Palin’s Pilate in Monty Python's Life of Brian, who lisps and mispronounces his r's as w's. In Martin Scorsese's The Last Temptation of Christ (1988), Pilate is played by David Bowie, who appears as "gaunt and eerily hermaphrodite." Bowie's Pilate speaks with a British accent, contrasting with the American accent of Jesus (Willem Dafoe). The trial takes place in Pilate's private stables, implying that Pilate does not think the judgment of Jesus very important, and no attempt is made to take any responsibility from Pilate for Jesus's death, which he orders without any qualms.

Mel Gibson's 2004 film The Passion of the Christ portrays Pilate, played by Hristo Shopov, as a sympathetic, noble-minded character, fearful that the Jewish priest Caiaphas will start an uprising if he does not give in to his demands. He expresses disgust at the Jewish authorities' treatment of Jesus when Jesus is brought before him and offers Jesus a drink of water. McDonough argues that "Shopov gives us a very subtle Pilate, one who manages to appear alarmed though not panicked before the crowd, but who betrays far greater misgivings in private conversation with his wife."

Interesting facts about Pontius Pilate

- He is venerated as a saint by the Ethiopian Church with a feast day on 19 June, and was historically venerated by the Coptic Church, with a feast day of 25 June.

- Pilate's washing his hands of responsibility for Jesus's death in Matthew 27:24 is a commonly encountered image in the popular imagination, and is the origin of the English phrase "to wash one's hands of (the matter)", meaning to refuse further involvement with or responsibility for something.

- Parts of the dialogue attributed to Pilate in the Gospel of John have become particularly famous sayings.

- The Gospels' deflection of responsibility for Jesus's crucifixion from Pilate to the Jews has been blamed for fomenting antisemitism from the Middle Ages through the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

- In 2018, an inscription on a thin copper-alloy sealing ring that had been discovered at Herodium was uncovered using modern scanning techniques. The inscription reads ΠΙΛΑΤΟ(Υ) (Pilato(u)), meaning "of Pilate". The name Pilatus is rare, so the ring could be associated with Pontius Pilate; however, given the cheap material, it is unlikely that he would have owned it. It is possible that the ring belonged to another individual named Pilate, or that it belonged to someone who worked for Pontius Pilate.

Pontius Pilate Quotes

- numquid ego Iudaeus sum? ("Am I a Jew?")

- Quid est veritas? ("What is truth?")

- Ecce homo ("Behold the man!")

- Ecce rex vester]], ("Behold your king!")

- Quod scripsi, scripsi ("What I have written, I have written").

Images for kids

-

Bronze prutah minted by Pontius Pilate in Jerusalem.Reverse: Greek letters ΤΙΒΕΡΙΟΥ ΚΑΙΣΑΡΟΣ and date LIϚ (year 16 = 29/30), surrounding simpulum.Obverse: Greek letters ΙΟΥΛΙΑ ΚΑΙΣΑΡΟΣ, three bound heads of barley, the outer two heads drooping.

-

Mosaic of Christ before Pilate, Basilica of Sant'Apollinare Nuovo in Ravenna, early sixth century. Pilate washes his hands in a bowl held by a figure on the right.

-

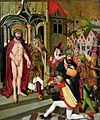

Panel from the Magdeburg Ivories depicting Pilate at the Flagellation of Christ, German, tenth century

-

Ecce Homo from the Legnica Polyptych by Nikolaus Obilman, Silesia, 1466 CE. Pilate stands beside Christ in a Jewish hat and golden robes.

See also

In Spanish: Poncio Pilato para niños

In Spanish: Poncio Pilato para niños

- List of biblical figures identified in extra-biblical sources