Racial Integrity Act of 1924 facts for kids

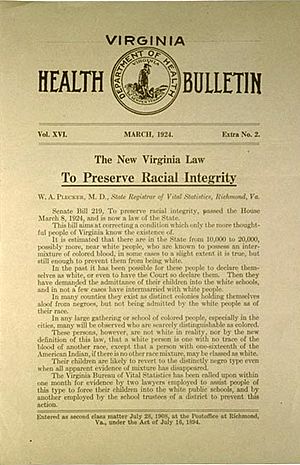

In 1924, the Virginia General Assembly enacted the Racial Integrity Act. The act reinforced racial segregation by prohibiting interracial marriage and classifying as "white" a person "who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian." The act, an outgrowth of eugenist and scientific racist propaganda, was pushed by Walter Plecker, a white supremacist and eugenist who held the post of registrar of Virginia Bureau of Vital Statistics.

The Racial Integrity Act required that all birth certificates and marriage certificates in Virginia to include the person's race as either "white" or "colored." The Act classified all non-whites, including Native Americans, as "colored." The act was part of a series of "racial integrity laws" enacted in Virginia to reinforce racial hierarchies and prohibit the mixing of races; other statutes included the Public Assemblages Act of 1926 (which required the racial segregation of all public meeting areas) and a 1930 act that defined any person with even a trace of African ancestry as black (thus codifying the so-called "one-drop rule").

In 1967, the Racial Integrity Act was e officially overturned by the United States Supreme Court in their ruling Loving v. Virginia. In 2001, the Virginia General Assembly passed a resolution that condemned the Racial Integrity Act for its "use as a respectable, 'scientific' veneer to cover the activities of those who held blatantly racist views."

Contents

History leading to the laws' passage: 1859–1924

In the 1920s, Virginia's registrar of statistics, Dr. Walter Ashby Plecker, was allied with the newly founded Anglo-Saxon Clubs of America in persuading the Virginia General Assembly to pass the Racial Integrity Law of 1924. The club was founded in Virginia by John Powell of Richmond in the fall of 1922; within a year the club for white males had more than 400 members and 31 posts in the state.

In 1923, the Anglo-Saxon Club founded two posts in Charlottesville, one for the town and one for students at the University of Virginia. A major goal was to end "amalgamation" by racial intermarriage. Members also claimed to support Anglo-Saxon ideas of fair play. Later that fall, a state convention of club members was to be held in Richmond.

In the following five decades, other states followed Indiana's example by implementing the eugenic laws. Wisconsin was the first state to enact legislation that required the medical certification of persons who applied for marriage licenses. The law that was enacted in 1913 generated attempts at similar legislation in other states.

Anti-miscegenation laws, banning interracial marriage between whites and non-whites, had existed long before the emergence of eugenics. First enacted during the Colonial era when slavery had become essentially a racial caste, such laws were in effect in Virginia and in much of the United States until the 1960s.

The first law banning all marriage between whites and Blacks was enacted in the colony of Virginia in 1691. This example was followed by Maryland (in 1692) and several of the other Thirteen Colonies. By 1913, 30 out of the then 48 states (including all Southern states) enforced such laws.

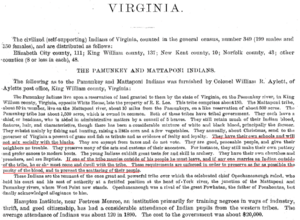

The Pocahontas exception

The Racial Integrity Act was subject to the Pocahontas Clause (or Pocahontas Exception), which allowed people with claims of less than 1/16 American Indian ancestry to still be considered white, despite the otherwise unyielding climate of one-drop rule politics. The exception regarding Native blood quantum was included as an amendment to the original Act in response to concerns of Virginia elites, including many of the First Families of Virginia, who had always claimed descent from Pocahontas with pride, but now worried that the new legislation would jeopardize their status. The exception stated:

It shall thereafter be unlawful for any white person in this State to marry any save a white person, or a person with no other admixture of blood than white and American Indian. For the purpose of this act, the term "white person" shall apply only to the person who has no trace whatsoever of any blood other than Caucasian; but persons who have one-sixteenth or less of the blood of the American Indian and have no other non-Caucasic blood shall be deemed to be white persons".

While definitions of "Indian", "colored" and variations of these were established and altered throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, this was the first direct case of whiteness itself being defined officially.

Enforcement

Once these laws were passed, Plecker was in the position to enforce them. Gov. E. Lee Trinkle, a year after signing the act, asked Plecker to ease up on the Indians and not "embarrass them any more than possible." Plecker responded, "I am unable to see how it is working any injustice upon them or humiliation for our office to take a firm stand against their intermarriage with white people, or to the preliminary steps of recognition as Indians with permission to attend white schools and to ride in white coaches."

Unsatisfied with the "Pocahontas Exception", eugenicists introduced an amendment to narrow loopholes to the Racial Integrity Act. This was considered by the Virginia General Assembly in February 1926, but it failed to pass. If adopted, the amendment would have reclassified thousands of "white" people as "colored" by more strictly implementing the "one-drop rule" of ancestry as applied to American Indian ancestry.

Plecker reacted strongly to the Pocahontas Clause with fierce concerns of the white race being "swallowed up by the quagmire of mongrelization", particularly after marriage cases like that of the Johns and Sorrels, in which the women of these couples argued that the family members listed as "colored" had actually been Native American because of historically unclear categorizing.

Implementation and consequences: 1924–1979

The combined effect of these two laws adversely affected the continuity of Virginia's American Indian tribes. The Racial Integrity Act called for only two racial categories to be recorded on birth certificates, rather than the traditional six: "white" and "colored" (which now included Indian and all discernible mixed race persons). The effects were quickly seen. In 1930, the US Census for Virginia recorded 779 Indians; by 1940, that number had been reduced to 198. In effect, Indians were being erased as a group from official records.

In addition, as Plecker admitted, he enforced the Racial Integrity Act extending far beyond his jurisdiction in the segregated society. For instance, he pressured school superintendents to exclude mixed-race (then called mulatto) children from white schools. Plecker ordered the exhumation of dead people of "questionable ancestry" from white cemeteries to be reinterred elsewhere.

Indians reclassified as colored

As registrar, Plecker directed the reclassification of nearly all Virginia Indians as colored on their birth and marriage certificates, because he was convinced that most Indians had African heritage and were trying to "pass" as Indian to evade segregation. Consequently, two or three generations of Virginia Indians had their ethnic identity altered on these public documents. Fiske reported that Plecker's tampering with the vital records of the Virginia Indian tribes made it impossible for descendants of six of the eight tribes recognized by the state to gain federal recognition, because they could no longer prove their American Indian ancestry by documented historical continuity.

Responses to the Racial Integrity Act

In the early twentieth century, minorities in everyday southern society feared to voice their opinions due to severe oppression. Magazines such as the Richmond Planet offered the Black community a voice and the opportunity to have their concerns heard. The Richmond Planet made a difference in society by openly expressing the opinions of minorities in society. After the passing of the Racial Integrity Act of 1924 the Richmond Planet published the article "Race Amalgamation Bill Being Passed in Va. Legislature. Much Discussion Here on race Integrity and Mongrelization ... Bill Would Prohibit Marriage of Whites and Non-whites ..."Skull of Bones" Discusses race question.". The journalist opened the article with the Racial Integrity Act and gave a brief synopsis of the act. Then followed statements from the creators of the Racial Integrity Act, John Powell and Earnest S. Cox. Mr. Powell believed that the Racial Integrity Act was needed as "maintenance of the integrity of the white race to preserve its superior blood" and Cox believed in what he called "the great man concept" which means that if the races were to intersect that it would lower the rate of great white men in the world. He defended his position by saying that non-whites would agree with his ideology:

The sane and educated Negro does not want social equality ... They do not want intermarriage or social mingling any more than does the average American white man wants it. They have race pride as well as we. They want racial purity as much as we want it. There are both sides to the question and to form an unbiased opinion either way requires a thorough study of the matter on both sides.

Supreme Court, repeals and apology: 1967–2002

In 1967 the US Supreme Court ruled in Loving v. Virginia that the portion of the Racial Integrity Act that criminalized marriages between "whites" and "nonwhites" was found to be contrary to the guarantees of equal protection of citizens under the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. In 1975, Virginia's Assembly repealed the remainder of the Racial Integrity Act. In 2001, the legislature overwhelmingly passed a bill (HJ607ER) to express the assembly's profound regret for its role in the eugenics movement. On May 2, 2002, Governor Mark R. Warner issued a statement also expressing "profound regret for the commonwealth's role in the eugenics movement."