Sally Hemings facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Sally Hemings

|

|

|---|---|

| Born |

Sarah Hemings

c. 1773 Charles City County, Virginia, British America

|

| Died | 1835 (aged 61–62) |

| Known for | Enslaved woman who had children by Thomas Jefferson |

| Children | 6, including Harriet, Madison, and Eston |

| Parent(s) | Betty Hemings John Wayles |

| Relatives | Hemings family |

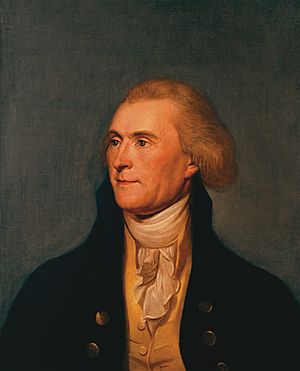

Sarah "Sally" Hemings (c. 1773 – 1835) was an enslaved woman with one-quarter African ancestry owned by president of the United States Thomas Jefferson, one of many he inherited from his father-in-law, John Wayles.

Hemings's mother Elizabeth (Betty) was bi-racial, the child of Susannah, an African woman and Captain John Hemings. Sally's father was John Wayles who was the father of Jefferson's wife Martha. Therefore, she was half-sister to Jefferson's wife and approximately three quarters white. Martha Wayles Jefferson died in 1782 when Sally was about 9 years old. Hemings reportedly (according to Abigail Adams letters) had a strong resemblance to Martha Jefferson and a certain naivete or childishness evidenced when she visited the Adamses in London before going on to France to bring Jefferson's daughter to him. At the time Hemings would have been approximately fourteen years old, although Adams believed she was 15 or 16.

During the 26 months Sally Hemings lived with Jefferson in Paris, she was a free woman and a paid servant, slavery not being legal in France. During this time, under circumstances that are not well understood, she and Jefferson began having intimate relations.

As attested by her son, Madison Hemings, she later negotiated with Jefferson that she would return to Virginia and resume her slave status as long as all their children would be emancipated upon turning 21. Multiple lines of evidence, including modern DNA analyses, indicate that Jefferson was the father of her six children. Four of Hemings' children survived into adulthood. Hemings died in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 1835.

The historical question of whether Jefferson was the father of Hemings' children is the subject of the Jefferson–Hemings controversy. Following renewed historical analysis in the late 20th century, two different societies dedicated to preserving the legacy of Jefferson hired commissions which reached opposite conclusions. The Thomas Jefferson Foundation hired a commission of scholars and scientists who worked with a 1998-1999 genealogical DNA test that was published in 2000 that found a match between the Jefferson male line and a descendant of Hemings' youngest son, Eston Hemings. The Foundation asserted that Jefferson fathered Eston and likely her other five children as well. However, The Thomas Jefferson Heritage Society commissioned a panel of Scholars of History in 2001 that unanimously agreed that it has not been proven that Thomas Jefferson fathered Sally Hemings' children.

In 2018, the Thomas Jefferson Foundation of Monticello announced its plans to have an exhibit titled Life of Sally Hemings, and affirmed that it was treating as a settled issue that Jefferson was the father of her known children. The exhibit opened in June 2018.

Contents

Early life

Sally Hemings was born about 1773 to Elizabeth (Betty) Hemings (1735–1807), a woman also born into slavery. Sally's father was their slave owner John Wayles (1715–1773). Betty's parents were another enslaved woman, a "full-blooded African", and a white English sea captain, whose surname was Hemings. Annette Gordon-Reed speculates that Betty's mother's name was Parthena (or Parthenia), based on the wills of Francis Eppes IV and John Wayles. Captain Hemings tried to purchase them from Eppes, but the planter refused. Upon Eppes' passing, Parthena and Betty were inherited by his daughter, Martha Eppes, who took them with her as personal slaves upon her marriage to Wayles.

John Wayles was the son of Edward and Ellen (née Ashburner) Wayles, both from Lancaster, England. Following Martha's death, Wayles remarried and was widowed twice more. Several sources assert that, Wayles took Betty Hemings as his concubine, and had six children by her during the last 12 years of his life, the youngest of these being Sally Hemings. These children were younger half-siblings to his daughters by his wives. His first child, Martha Wayles (named after her mother, John Wayles' first wife), married the young planter and future president Thomas Jefferson.

The children of Betty Hemings and John Wayles were three-quarters European in ancestry and fair-skinned. According to the 1662 Virginia Slave Law, children born to enslaved mothers were considered enslaved people under the principle of partus sequitur ventrem: the enslaved status of a child followed that of the mother. Betty and her children, including Sally Hemings and all Sally's children, were legally slaves, even though the fathers were their white slave owners and the children were of majority-white ancestry.

After John Wayles died in 1773, his daughter Martha and her husband, Thomas Jefferson, inherited the Hemings family among a total of 135 enslaved people from Wayles' estate, along with 11,000 acres (4,500 ha) of land. The youngest of the six Wayles-Hemings children was Sally, an infant that year and about 25 years younger than Martha. She, her siblings, their mother, and various other enslaved people were brought to Monticello, Jefferson's home. As the mixed-race Wayles-Hemings children grew up at Monticello, they were trained and given assignments as skilled artisans and domestic servants, at the top of the enslaved hierarchy. Betty Hemings' other children and their descendants, also mixed race, were bestowed privileged assignments, as well. None worked in the fields.

Hemings in Paris

In 1784, Thomas Jefferson was appointed the American envoy to France; he took his eldest daughter Martha (Patsy) with him to Paris, as well as several of the enslaved people he owned. Among them was Sally's elder brother James Hemings, who became a chef trained in French cuisine. Jefferson left his two younger daughters in the care of their aunt and uncle, Francis and Elizabeth Wayles Eppes of Eppington in Chesterfield County, VA. After his youngest daughter, Lucy Elizabeth, died in 1784, Jefferson sent for his surviving daughter, nine-year-old Mary (Polly), to live with him. The enslaved child, Sally Hemings, was chosen to accompany Polly to France after an older enslaved woman became pregnant and could not make the journey. Correspondence between Jefferson and Abigail Adams indicates that Jefferson originally arranged for Polly to "be in the care of her nurse, a black woman, to whom she is confided with safety"; Adams wrote back: "The old Nurse whom you expected to have attended her, was sick and unable to come. She has a Girl about 15 or 16 with her."

In 1787, Sally, aged 14, accompanied Polly to London and then to Paris, where the widowed Jefferson, aged 44 at the time, was serving as the United States Minister to France. Hemings spent two years there. Most historians believe Jefferson and Hemings' relationship began while they were in France or soon after their return to Monticello. The exact nature of their relationship remains unclear. The Monticello exhibition on Hemings acknowledged this uncertainty, while noting the power imbalance inherent in the relationship between a wealthy white male envoy and a 14-year-old quarter-black enslaved female. Hemings remained enslaved in Jefferson's house until his death in 1826. In 2017, a room identified as her quarters at Monticello, under the south terrace, was discovered in an archeological examination. It is being restored and refurbished.

Polly and Sally landed in London, where they stayed with Abigail and John Adams from June 26 until July 10, 1787. Jefferson's associate, a Mr. Petit, arranged transportation and escorted the girls to Paris. In a letter to Jefferson on June 27, 1787, Abigail wrote: "The Girl who is with [Polly] is quite a child, and Captain Ramsey is of opinion will be of so little Service that he had better carry her back with him. But of this you will be a judge. She seems fond of the child and appears good natured." On July 6, Abigail wrote to Jefferson, "The Girl she has with her, wants more care than the child, and is wholy incapable of looking properly after her, without some superiour to direct her."

Sally Hemings remained in France for 26 months. Slavery had been abolished in that country after the Revolution in 1789; Jefferson paid wages to her and James while they were in Paris. He paid Sally Hemings the equivalent of $2 a month. In comparison, he paid James Hemings $4 a month as chef-in-training, and his Parisian scullion $2.50 a month; the other French servants earned from $8 to $12 a month. Toward the end of their stay, James used his money to pay for a French tutor and to learn the language, and Sally was also learning French. There is no record of where she lived: it may have been with Jefferson and her brother in the Hôtel de Langeac on the Champs-Elysées, or at the convent Abbaye de Penthemont where the girls Maria and Martha were schooled. Whatever the weekday arrangements, Jefferson and his retinue spent weekends together at his villa. Jefferson purchased some fine clothing for Hemings, which suggests that she accompanied Martha as a lady's maid to formal events.

According to her son Madison's memoir, Hemings became pregnant by Jefferson in Paris. She was about 16 at the time. Under French law, Sally and James could have petitioned for their freedom, but if she returned to Virginia with Jefferson, it would be as an enslaved person. She agreed to return with him to the United States, based on his promise to free her children when they came of age (at 21). Hemings' strong ties to her mother, siblings, and extended family likely drew her back to Monticello.

Return to the United States and children's freedom

In 1789, Sally and James Hemings returned to the United States with Jefferson, who was 46 years old and seven years a widower. As shown by Jefferson's father-in-law, John Wayles, wealthy Virginia widowers frequently had relations with enslaved women. This would not have been seen as unusual for Jefferson either. White society simply expected such men to be discreet about these relationships.

According to Madison Hemings, Sally's first child died soon after her return from Paris. Hemings had six children after her return to the US; their complete names are in some cases uncertain:

- Harriet Hemings [I] (October 5, 1795 – December 1797)

- Beverley Hemings, possibly William Beverley Hemings (April 1, 1798 – after 1873)

- Daughter, possibly named Thenia Hemings after Sally's sister (born in 1799 and died in infancy)

- Harriet Hemings [II] (May 1801 – Unknown)

- Madison Hemings, possibly James Madison Hemings (January 19, 1805 – November 28, 1877)

- Eston Hemings, possibly named Thomas Eston Hemings (May 21, 1808 – January 3, 1856)

Jefferson recorded births of enslaved peoples in his Farm Book. Unlike his practice in recording births of other enslaved peoples, he did not note the father of Sally Hemings' children.

Sally Hemings' documented duties at Monticello included being a nursemaid-companion, lady's maid, chambermaid, and seamstress. It is not known whether she was literate, and she left no known writings. She was described as very fair, with "straight hair down her back". Jefferson's grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, described her as "light colored and decidedly good looking". She is believed to have lived as an adult in a room in Monticello's "South Dependencies", a wing of the mansion accessible to the main house through a covered passageway.

In 2017, the Monticello Foundation announced that what they believe to be Hemings's room, adjacent to Jefferson's bedroom, had been found through an archeological excavation, as part of the Mountaintop Project. It was space that had been converted to other public uses in 1941. Hemings' room will be restored and refurbished as part of a major restoration project for the complex. Its goals include telling the stories of all the families at Monticello, both enslaved and free.

Hemings never married. As an enslaved person, she could not have a marriage recognized under Virginia law, but many enslaved people at Monticello are known to have taken partners in common-law marriages and had stable lives. No such partnership of Hemings is noted in the records. She kept her children close by while she worked at Monticello. According to her son Madison, while young, the children "were permitted to stay about the 'great house', and only required to do such light work as going on errands". At the age of 14, each of the children began their training: the brothers with the plantation's skilled master of carpentry, and Harriet as a spinner and weaver. The three boys all learned to play the violin, which Jefferson himself played.

In 1822, at the age of 24, Beverley "ran away" from Monticello and was not pursued. His sister Harriet Hemings, 21, followed in the same year, apparently with at least tacit permission. The overseer, Edmund Bacon, said that he gave her $50 (US$1,221 in 2022 dollars ) and put her on a stagecoach to the North, presumably to join her brother. In his memoir, published posthumously, Bacon said Harriet was "near white and very beautiful", and that people said Jefferson freed her because she was his daughter. However, Bacon did not believe this to be true, citing someone else coming out of Sally Hemings' bedroom. The name of this person was left out by Rev. Hamilton W. Pierson in his 1862 book because he did not wish to cause pain to anyone living at that time.

Jefferson formally freed only two enslaved people while he was living: Sally's older brothers Robert, who had to buy his freedom, and James, who was required to train his brother Peter for three years to get his freedom. Jefferson eventually (primarily posthumously, through his will) freed all of Sally's surviving children, Beverly, Harriet, Madison, and Eston, as they came of age. (Harriet was the only enslaved woman Jefferson allowed to go free.) Of the hundreds of enslaved individuals he legally owned, Jefferson freed only five in his will, all men from the Hemings family. They were also the only enslaved family group freed by Jefferson. Sally Hemings' children were seven-eighths European in ancestry, and three of the four entered white society after gaining their freedom; their descendants likewise identified as white. His will also petitioned the legislature to allow the freed Hemingses to stay in the state.

No documentation has been found for Sally Hemings's own emancipation. Jefferson's daughter Martha (Patsy) Randolph informally freed the elderly Hemings after Jefferson's death, by giving her "her time", as was a custom. As the historian Edmund S. Morgan has noted, "Hemings herself was withheld from auction and freed at last by Jefferson's daughter, Martha Jefferson Randolph, who was, of course, her niece." This informal freedom allowed Hemings to live in Virginia with her two youngest sons in nearby Charlottesville for the next nine years until her death. In the Albemarle County 1833 census, all three were recorded as free persons of color. Hemings lived to see a grandchild born in a house that her sons owned.

Although Jefferson inherited great wealth at a young age, he was bankrupt by the time he died. His entire estate, including most enslaved people, was sold by his daughter Martha to repay his debts.

Jefferson–Hemings controversy

The Jefferson–Hemings controversy is the question of whether Jefferson fathered any or all of Sally Hemings six children of record. There were rumors as early as the 1790s. Jefferson's relationship with Hemings was first publicly reported in 1802 by one of Jefferson's enemies, a political journalist named James T. Callender, after he noticed several light-skinned enslaved people at Monticello. He wrote that Jefferson "kept, as his concubine, one of his own slaves" and had "several children" by her. After that the story became widespread, spread by newspapers and by Jefferson's Federalist opponents. Jefferson himself is never recorded to have publicly denied this allegation. However, several members of his family did. In the 1850s, Jefferson's eldest grandson, Thomas Jefferson Randolph, said that Peter Carr, a nephew of Jefferson, had fathered Hemings's children, rather than Jefferson himself. This information was published and became the common wisdom, with major historians of Jefferson denying Jefferson's paternity of Hemings's children for the next 150 years.

Since 1998 and the DNA study, several historians have concluded that Jefferson maintained a long relationship with Hemings and fathered six children with her, four of whom survived to adulthood. In an article that appeared in Science, eight weeks after the DNA study, Eugene Foster, the lead co-author of the DNA study, is reported to have "made it clear that Thomas was only one of eight or more Jeffersons who may have fathered Eston Hemings". The Thomas Jefferson Foundation (TJF) published in 2000 an independent historic review in combination with the DNA data, as did the National Genealogical Society in 2001; scholars involved mostly concluded Jefferson was probably the father of all Hemings' children.

In 2012, the Smithsonian Institution and the Thomas Jefferson Foundation held a major exhibit at the National Museum of American History: Slavery at Jefferson's Monticello: The Paradox of Liberty; it says that "the documentary and genetic evidence ... strongly support the conclusion that [Thomas] Jefferson was the father of Sally Hemings' children."

Children's lives

In 2008, Gordon-Reed published The Hemingses of Monticello: An American Family, which explored the extended family, including James's and Sally's lives in France, Monticello and Philadelphia, during Thomas Jefferson's lifetime. She was not able to find much new information about Beverley or Harriet Hemings, who left Monticello as young adults, moving north and probably changing their names.

Madison Hemings's memoir (edited and put into written form by journalist S. F. Wetmore in the Pike County Republican in 1873) and other documentation, including a wide variety of historical records, and newspaper accounts, has revealed some details of the lives of the Beverley and Harriet, and younger sons Madison and Eston Hemings (later Eston Jefferson), and of their descendants. Eventually, three of Sally Hemings' four surviving children (Beverley, Harriet, and Eston, but not Madison) chose to identify as white adults in the North; they were seven-eighths European in ancestry, and this was consistent with their appearance. Harriet was described by Edmund Bacon, the longtime Monticello overseer, as "nearly as white as anybody, and very beautiful". In his memoir, Madison wrote that both Beverley and Harriet married well in the white community in the Washington, DC, area. For some time, Madison wrote to Beverley and Harriet and learned of their marriages. He knew that Harriet had children and was living in Maryland. But gradually she and Beverley stopped responding to his letters, and the siblings lost touch. Madison also claimed publicly in the 1873 memoir that he was Thomas Jefferson's son, and he had done likewise on the 1870 US Census.

Both Madison and Eston married free women of color in Charlottesville. After their mother's death in 1835, they and their families moved to Chillicothe in the free state of Ohio. Census records classified them as "mulatto", at that time meaning mixed-race. The census enumerator, usually a local person, classified individuals in part according to who their neighbors were and what was known of them. Around 60 years later, a Chillicothe newswriter reminisced in 1902 about his acquaintance with Eston (then a well-known local musician), whom he described as "a remarkably fine looking colored man" with a "striking resemblance to Jefferson" recognized by others, who had already heard a rumors of his paternity and were credulous of it.

High demand for slaves in the Deep South and passage of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 heightened the risk for free black people of being kidnapped by slave catchers, as they needed little documentation to claim black people as fugitives. Legally free people of color, Eston and his family later moved to Madison, Wisconsin, to be farther away from slave catchers. There he changed his name to "Eston H. Jefferson" to acknowledge his paternity, and all his family adopted the surname. From then on, the Jeffersons lived in the white community.

Madison's family were the only Monticello Hemings descendants who continued to identify with the black community. They intermarried within the community of free people of color before the Civil War. Over time, some of their descendants passed into the white community, while many others continued within the black community.

Both Eston and Madison achieved some success in life, were well-respected by their contemporaries, and had children who built on their successes. They worked as carpenters, and Madison also had a small farm. Eston became a professional musician and bandleader, "a master of the violin, and an accomplished 'caller' of dances", who "always officiated at the 'swell' entertainments of Chillicothe". He was in demand across southern Ohio. The aforementioned journalist neighbor in Chillicothe described him thus: "Quiet, unobtrusive, polite and decidedly intelligent, he was soon very well and favorably known to all classes of our citizens, for his personal appearance and gentlemanly manners attracted everybody's attention to him."

Grandchildren and other descendants

Madison's descendants

Madison's sons fought on the Union side in the Civil War. Thomas Eston Hemings enlisted in the United States Colored Troops (USCT); captured, he spent time at the Andersonville POW camp and died in a POW camp in Meridian, Mississippi. According to a Hemings descendant, his brother James attempted to cross Union lines and "pass" as a white man to enlist in the Confederate army to rescue him. Later, James Hemings was rumored to have moved to Colorado and perhaps passed into white society. Like some others in the family, he disappeared from the record, and the rest of his biography remains unknown.

A third son, William Hemings, enlisted in the regular Union Army as a white man. Madison's last known male-line descendant, William, never married and was not known to have had children. He died in 1910 in a veterans' hospital.

Some of Madison Hemings' children and grandchildren who remained in Ohio suffered from the limited opportunities for blacks at that time, working as laborers, servants, or small farmers. They tended to marry within the mixed-race community in the region, who eventually became established as people of education and property.

Madison's daughter, Ellen Wayles Hemings, married Alexander Jackson Roberts, a graduate of Oberlin College. When their first son was young, they moved to Los Angeles, California, where the family and its descendants became leaders in the twentieth century. Their first son, Frederick Madison Roberts (1879–1952) – Sally Hemings' and Jefferson's great-grandson – was the first person of known black ancestry elected to public office on the West Coast: he served for nearly 20 years in the California State Assembly from 1919 to 1934. Their second son, William Giles Roberts, was also a civic leader. Their descendants have had a strong tradition of college education and public service.

Eston's descendants

Eston's sons also enlisted in the Union Army, both as white men from Madison, Wisconsin. His first son John Wayles Jefferson had red hair and gray eyes like his grandfather Jefferson. By the 1850s, John Jefferson in his twenties was the proprietor of the American Hotel in Madison. At one time he operated it with his younger brother Beverley. He was commissioned as a Union officer during the Civil War, during which he was promoted to the rank of Colonel and served at the Battle of Vicksburg. He wrote letters about the war to the newspaper in Madison for publication. After the war, John Jefferson returned to Wisconsin, where he frequently wrote for newspapers and published accounts about his war experiences. He later moved to Memphis, Tennessee, where he became a successful and wealthy cotton broker. He never married or had known children, and left a sizeable estate.

Eston's second son, Beverley Jefferson, also served in the regular Union Army. After operating the American Hotel with his brother John, he later separately operated the Capital Hotel. He also built a successful horse-drawn "omnibus" business. He and his wife Anna M. Smith had five sons, three of whom reached the professional class as a physician, attorney, and manager in the railroad industry. According to his 1908 obituary, Beverley Jefferson was "a likeable character at the Wisconsin capital and a familiar of statesmen for half a century". His friend Augustus J. Munson wrote, "Beverley Jefferson['s] death deserves more than a passing notice, as he was a grandson of Thomas Jefferson .... [He] was one of God's noblemen – gentle, kind, courteous, charitable." Beverley and Anna's great-grandson John Weeks Jefferson is the Eston Hemings descendant whose DNA was tested in 1998; it matched the Y-chromosome of the Thomas Jefferson male line.

There are known male-line descendants of Eston Hemings Jefferson, and known female-line descendants of Madison Hemings' three daughters: Sarah, Harriet, and Ellen.

Cultural depictions of Sally Hemings

Sally Hemings has been the main subject of a novel, a television mini-series, a stage play, two operas, and an operatic oratorio. She is also the subject of the second half of the film Jefferson in Paris. She has also appeared as a supporting character or a subject of discussion in many other shows and stage productions.

See also

In Spanish: Sally Hemings para niños

In Spanish: Sally Hemings para niños

- Thomas Jefferson and slavery

- List of slaves