Sydney Harbour Bridge facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Sydney Harbour Bridge |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Coordinates | 33°51′08″S 151°12′38″E / 33.85222°S 151.21056°E |

| Carries |

|

| Crosses | Port Jackson (Sydney Harbour) |

| Locale | Sydney, Australia () |

| Official name | Sydney Harbour Bridge |

| Owner | Government of New South Wales |

| Maintained by | Roads and Maritime Services |

| Preceded by | Gladesville Bridge |

| Characteristics | |

| Design | Through arch bridge |

| Total length | 1,149 m (3,770 ft) |

| Width | 48.8 m (160 ft) |

| Height | 134 m (440 ft) |

| Longest span | 503 m (1,650 ft) |

| Number of spans | 1 |

| Clearance below | 49 m (161 ft) at mid-span |

| History | |

| Constructed by | Dorman Long & Co |

| Construction begin | 28 July 1923 |

| Construction end | 19 January 1932 |

| Opened | 19 March 1932 |

| Inaugurated | 19 March 1932 |

| Statistics | |

| Toll | Time of day tolling (southbound only) |

|

Australian National Heritage List

|

|

| Official name | Sydney Harbour Bridge, Bradfield Hwy, Dawes Point - Milsons Point, NSW, Australia |

| Type | National Heritage List |

| Designated | 19 March 2007 |

| Reference no. | 105888 |

| Class | Historic |

| Place File No. | 1/12/036/0065 |

| Official name | Sydney Harbour Bridge, approaches and viaducts (road and rail); Pylon Lookout; Milsons Point Railway Station; Bradfield Park; Bradfield Park North; Dawes Point Park; Bradfield Highway |

| Type | State heritage (complex / group) |

| Designated | 25 June 1999 |

| Reference no. | 781 |

| Type | Road Bridge |

| Category | Transport - Land |

| Lua error in Module:Location_map at line 420: attempt to index field 'wikibase' (a nil value). | |

The Sydney Harbour Bridge, in Sydney Harbour, is a bridge that joins north Sydney with south Sydney. People can cross the bridge by car, walking or by train. There is a tunnel that goes underneath. The bridge is an important tourist attraction. The scenery attracts many tourists and people living in or near the city. One of the many attractions of the Harbour Bridge is its famous 'BridgeClimb'. Luna Park Sydney is located next to the bridge.

The bridge is 1,149 metres (3,770 feet) long, and 49 m (161 ft) wide. The highest point of the arch is 134 m (440 ft) tall. Building began on 19 March 1923 and ended in 1932. John Bradfield led the bridge's building.

The total financial cost of the bridge was AU£6.25 million, which was not paid off in full until 1988.[34]

Contents

Structure

The southern end of the bridge is located at Dawes Point in The Rocks area, and the northern end at Milsons Point in the lower North Shore area. There are six original lanes of road traffic through the main roadway, plus an additional two lanes of road traffic on its eastern side, using lanes that were formerly tram tracks. Adjacent to the road traffic, a path for pedestrian use runs along the eastern side of the bridge, whilst a dedicated path for bicycle use only runs along the western side; between the main roadway and the western bicycle path lies the North Shore railway line.

The main roadway across the bridge is known as the Bradfield Highway and is about 2.4 km (1.5 mi) long, making it one of the shortest highways in Australia.

Arch

The arch is composed of two 28-panel arch trusses; their heights vary from 18 m (59 ft) at the centre of the arch to 57 m (187 ft) at the ends next to the pylons.

The arch has a span of 504 m (1,654 ft) and its summit is 134 m (440 ft) above mean sea level; expansion of the steel structure on hot days can increase the height of the arch by 18 cm (7.1 in).

The total weight of the steelwork of the bridge, including the arch and approach spans, is 52,800 tonnes (52,000 long tons; 58,200 short tons), with the arch itself weighing 39,000 tonnes (38,000 long tons; 43,000 short tons). About 79% of the steel, specifically those technical sections constituting the curve of the arch, was imported pre-formed from England, with the rest being sourced from Newcastle. On site, the contractors (Dorman Long and Co.) set up two workshops at Milsons Point, at the site of the present day Luna Park, and fabricated the steel into the girders and other required parts.

The bridge is held together by six million Australian-made hand-driven rivets supplied by the McPherson company of Melbourne, the last being driven through the deck on 21 January 1932. The rivets were heated red-hot and inserted into the plates; the headless end was immediately rounded over with a large pneumatic rivet gun. The largest of the rivets used weighed 3.5 kg (8 lb) and was 39.5 cm (15.6 in) long. The practice of riveting large steel structures, rather than welding, was, at the time, a proven and understood construction technique, whilst structural welding had not at that stage been adequately developed for use on the bridge.

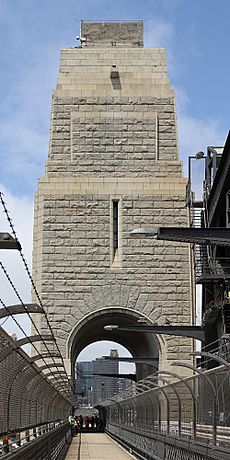

Pylons

At each end of the arch stands a pair of 89 m (292 ft) high concrete pylons, faced with granite. The pylons were designed by the Scottish architect Thomas S. Tait, a partner in the architectural firm John Burnet & Partners.

Some 250 Australian, Scottish, and Italian stonemasons and their families relocated to a temporary settlement at Moruya, NSW, 300 km (186 mi) south of Sydney, where they quarried around 18,000 m3 (635,664 cu ft) of granite for the bridge pylons. The stonemasons cut, dressed, and numbered the blocks, which were then transported to Sydney on three ships built specifically for this purpose. The Moruya quarry was managed by John Gilmore, a Scottish stonemason who emigrated with his young family to Australia in 1924, at the request of the project managers. The concrete used was also Australian-made and supplied from Kandos, New South Wales.

Abutments at the base of the pylons are essential to support the loads from the arch and hold its span firmly in place, but the pylons themselves have no structural purpose. They were included to provide a frame for the arch panels and to give better visual balance to the bridge. The pylons were not part of the original design, and were only added to allay public concern about the structural integrity of the bridge.

Although originally added to the bridge solely for their aesthetic value, all four pylons have now been put to use. The south-eastern pylon contains a museum and tourist centre, with a 360° lookout at the top providing views across the harbour and city. The south-western pylon is used by the New South Wales Roads and Traffic Authority (RTA) to support its CCTV cameras overlooking the bridge and the roads around that area. The two pylons on the north shore include venting chimneys for fumes from the Sydney Harbour Tunnel, with the base of the southern pylon containing the RMS maintenance shed for the bridge, and the base of the northern pylon containing the traffic management shed for tow trucks and safety vehicles used on the bridge.

In 1942 the pylons were modified to include parapets and anti-aircraft guns designed to assist in both Australia's defence and general war effort. The top level of stonework was never removed.

History

Early proposals

There had been plans to build a bridge as early as 1815, when convict and noted architect Francis Greenway reputedly proposed to Governor Lachlan Macquarie that a bridge be built from the northern to the southern shore of the harbour. In 1825, Greenway wrote a letter to the then "The Australian" newspaper stating that such a bridge would "give an idea of strength and magnificence that would reflect credit and glory on the colony and the Mother Country".

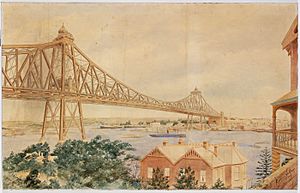

Nothing came of Greenway's suggestions, but the idea remained alive, and many further suggestions were made during the nineteenth century. In 1840, naval architect Robert Brindley proposed that a floating bridge be built. Engineer Peter Henderson produced one of the earliest known drawings of a bridge across the harbour around 1857. A suggestion for a truss bridge was made in 1879, and in 1880 a high-level bridge estimated at $850,000 was proposed.

In 1900, the Lyne government committed to building a new Central railway station and organised a worldwide competition for the design and construction of a harbour bridge. Local engineer Norman Selfe submitted a design for a suspension bridge and won the second prize of £500. In 1902, when the outcome of the first competition became mired in controversy, Selfe won a second competition outright, with a design for a steel cantilever bridge. The selection board were unanimous, commenting that, "The structural lines are correct and in true proportion, and... the outline is graceful". However due to an economic downturn and a change of government at the 1904 NSW State election construction never began.

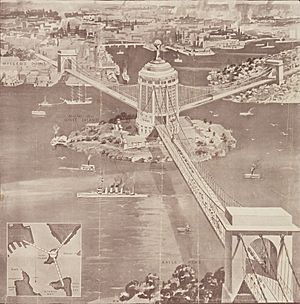

A unique three-span bridge was proposed in 1922 by Ernest Stowe with connections at Balls Head, Millers Point, and Balmain with a memorial tower and hub on Goat Island.

Planning

In 1914 John Bradfield was appointed "Chief Engineer of Sydney Harbour Bridge and Metropolitan Railway Construction", and his work on the project over many years earned him the legacy as the "father" of the bridge. Bradfield's preference at the time was for a cantilever bridge without piers, and in 1916 the NSW Legislative Assembly passed a bill for such a construction, however it did not proceed as the Legislative Council rejected the legislation on the basis that the money would be better spent on the war effort.

Following World War I, plans to build the bridge again built momentum. Bradfield persevered with the project, fleshing out the details of the specifications and financing for his cantilever bridge proposal, and in 1921 he travelled overseas to investigate tenders. On return from his travels Bradfield decided that an arch design would also be suitable and he and officers of the NSW Department of Public Works prepared a general design for a single-arch bridge based upon New York City's Hell Gate Bridge. In 1922 the government passed the Sydney Harbour Bridge Act No. 28, specifying the construction of a high-level cantilever or arch bridge across the harbour between Dawes Point and Milsons Point, along with construction of necessary approaches and electric railway lines, and worldwide tenders were invited for the project.

As a result of the tendering process, the government received twenty proposals from six companies; on 24 March 1924 the contract was awarded to British firm Dorman Long and Co Ltd, of Middlesbrough well known as the contractors who later built the similar Tyne Bridge of Newcastle Upon Tyne, for an arch bridge at a quoted price of AU£4,217,721 11s 10d. The arch design was cheaper than alternative cantilever and suspension bridge proposals, and also provided greater rigidity making it better suited for the heavy loads expected.

Bradfield and his staff were ultimately to oversee the bridge design and building process as it was executed by Dorman Long and Co, whose Consulting Engineer, Sir Ralph Freeman of Sir Douglas Fox and Partners, and his associate Mr. G.C. Imbault, carried out the detailed design and erection process of the bridge. Architects for the contractors were from the British firm John Burnet & Partners of Glasgow, Scotland. Lawrence Ennis, of Dorman Long, served as Director of Construction and primary onsite supervisor throughout the entire build, alongside Edward Judge, Dorman Long's Chief Technical Engineer, who functioned as Consulting and Designing Engineer.

The building of the bridge coincided with the construction of a system of underground railways in Sydney's CBD, known today as the City Circle, and the bridge was designed with this in mind. The bridge was designed to carry six lanes of road traffic, flanked on each side by two railway tracks and a footpath. Both sets of rail tracks were linked into the underground Wynyard railway station on the south (city) side of the bridge by symmetrical ramps and tunnels. The eastern-side railway tracks were intended for use by a planned rail link to the Northern Beaches; in the interim they were used to carry trams from the North Shore into a terminal within Wynyard station, and when tram services were discontinued in 1958, they were converted into extra traffic lanes. The Bradfield Highway, which is the main roadway section of the bridge and its approaches, is named in honour of Bradfield's contribution to the bridge.

Construction

Bradfield visited the site sporadically throughout the eight years it took Dorman Long to complete the bridge. Despite having originally championed a cantilever construction and the fact that his own arched general design was used in neither the tender process nor as input to the detailed design specification (and was anyway a rough copy of the Devil's Gate bridge produced by the NSW Works Department), Bradfield subsequently attempted to claim personal credit for Dorman Long's design. This led to a bitter argument, with Dorman Long maintaining that instructing other people to produce a copy of an existing design in a document not subsequently used to specify the final construction did not constitute personal design input on Bradfield's part. This friction ultimately led to a large contemporary brass plaque being bolted very tightly to the side of one of the granite columns of the bridge in order to makes things clear

The official ceremony to mark the "turning of the first sod" occurred on 28 July 1923, on the spot at Milsons Point on the north shore where two workshops to assist in building the bridge were to be constructed.

An estimated 469 buildings on the north shore, both private homes and commercial operations, were demolished to allow construction to proceed, with little or no compensation being paid. Work on the bridge itself commenced with the construction of approaches and approach spans, and by September 1926 concrete piers to support the approach spans were in place on each side of the harbour.

As construction of the approaches took place, work was also started on preparing the foundations required to support the enormous weight of the arch and loadings. Concrete and granite faced abutment towers were constructed, with the angled foundations built into their sides.

Once work had progressed sufficiently on the support structures, a giant "creeper crane" was erected on each side of the harbour. These cranes were fitted with a cradle, and then used to hoist men and materials into position to allow for erection of the steelwork. To stabilise works while building the arches, tunnels were excavated on each shore with steel cables passed through them and then fixed to the upper sections of each half-arch to stop them collapsing as they extended outwards.

Arch construction itself began on 26 October 1928. The southern end of the bridge was worked on ahead of the northern end, to detect any errors and to help with alignment. The cranes would "creep" along the arches as they were constructed, eventually meeting up in the middle. In less than two years, on Tuesday, 19 August 1930, the two halves of the arch touched for the first time. Workers riveted both top and bottom sections of the arch together, and the arch became self-supporting, allowing the support cables to be removed. On 20 August 1930 the joining of the arches was celebrated by flying the flags of Australia and the United Kingdom from the jibs of the creeper cranes.

Once the arch was completed, the creeper cranes were then worked back down the arches, allowing the roadway and other parts of the bridge to be constructed from the centre out. The vertical hangers were attached to the arch, and these were then joined with horizontal crossbeams. The deck for the roadway and railway were built on top of the crossbeams, with the deck itself being completed by June 1931, and the creeper cranes were dismantled. Rails for trains and trams were laid, and road was surfaced using concrete topped with asphalt. Power and telephone lines, and water, gas, and drainage pipes were also all added to the bridge in 1931.

The pylons were built atop the abutment towers, with construction advancing rapidly from July 1931. Carpenters built wooden scaffolding, with concreters and masons then setting the masonry and pouring the concrete behind it. Gangers built the steelwork in the towers, while day labourers manually cleaned the granite with wire brushes. The last stone of the north-west pylon was set in place on 15 January 1932, and the timber towers used to support the cranes were removed.

On 19 January 1932, the first test train, a steam locomotive, safely crossed the bridge. Load testing of the bridge took place in February 1932, with the four rail tracks being loaded with as many as 96 steam locomotives positioned end-to-end. The bridge underwent testing for three weeks, after which it was declared safe and ready to be opened. The construction worksheds were demolished after the bridge was completed, and the land that they were on is now occupied by Luna Park.

The standards of industrial safety during construction were poor by today's standards. Sixteen workers died during construction, but surprisingly only two from falling off the bridge. Several more were injured from unsafe working practices undertaken whilst heating and inserting its rivets, and the deafness experienced by many of the workers in later years was blamed on the project. Henri Mallard between 1930 and 1932 produced hundreds of stills and film footage which reveal at close quarters the bravery of the workers in tough Depression-era conditions.

Interviews were conducted between 1982-1989 with a variety of tradesmen who worked on the building of the bridge. Among the tradesmen interviewed were drillers, riveters, concrete packers, boilermakers, riggers, ironworkers, plasterers, stonemasons, an official photographer, sleepcutters, engineers and draughtsmen.

The total financial cost of the bridge was AU£6.25 million, which was not paid off in full until 1988.

Opening

The bridge was formally opened on Saturday, 19 March 1932. Among those who attended and gave speeches were the Governor of New South Wales, Sir Philip Game, and the Minister for Public Works, Lawrence Ennis. The Premier of New South Wales, Jack Lang, was to open the bridge by cutting a ribbon at its southern end.

However, just as Lang was about to cut the ribbon, a man in military uniform rode up on a horse, slashing the ribbon with his sword and opening the Sydney Harbour Bridge in the name of the people of New South Wales before the official ceremony began. He was promptly arrested. The ribbon was hurriedly retied and Lang performed the official opening ceremony and Game thereafter inaugurated the name of the bridge as 'Sydney Harbour Bridge' and the associated roadway as the 'Bradfield Highway'. After they did so, there was a 21-gun salute and an RAAF flypast. The intruder was identified as Francis de Groot. He was convicted of offensive behaviour and fined £5 after a psychiatric test proved he was sane, but this verdict was reversed on appeal. De Groot then successfully sued the Commissioner of Police for wrongful arrest, and was awarded an undisclosed out of court settlement. De Groot was a member of a right-wing paramilitary group called the New Guard, opposed to Lang's leftist policies and resentful of the fact that a member of the Royal Family had not been asked to open the bridge. De Groot was not a member of the regular army but his uniform allowed him to blend in with the real cavalry. This incident was one of several involving Lang and the New Guard during that year.

A similar ribbon-cutting ceremony on the bridge's northern side by North Sydney's mayor, Alderman Primrose, was carried out without incident. It was later discovered that Primrose was also a New Guard member but his role in and knowledge of the de Groot incident, if any, are unclear. The pair of golden scissors used in the ribbon cutting ceremonies on both sides of the bridge was also used to cut the ribbon at the dedication of the Bayonne Bridge, which had opened between Bayonne, New Jersey, and New York City the year before.

Despite the bridge opening in the midst of the Great Depression, opening celebrations were organised by the Citizens of Sydney Organising Committee, an influential body of prominent men and politicians that formed in 1931 under the chairmanship of the Lord Mayor to oversee the festivities. The celebrations included an array of decorated floats, a procession of passenger ships sailing below the bridge, and a Venetian Carnival. A message from a primary school in Tottenham, 515 km (320 mi) away in rural New South Wales, arrived at the bridge on the day and was presented at the opening ceremony. It had been carried all the way from Tottenham to the bridge by relays of school children, with the final relay being run by two children from the nearby Fort Street Boys' and Girls' schools. After the official ceremonies, the public was allowed to walk across the bridge on the deck, something that would not be repeated until the 50th anniversary celebrations. Estimates suggest that between 300,000 and one million people took part in the opening festivities, a phenomenal number given that the entire population of Sydney at the time was estimated to be 1,256,000.

There had also been numerous preparatory arrangements. On 14 March 1932, three postage stamps were issued to commemorate the imminent opening of the bridge. Several songs were composed for the occasion. In the year of the opening, there was a steep rise in babies being named Archie and Bridget in honour of the bridge.

The bridge itself was regarded as a triumph over Depression times, earning the nickname "the Iron Lung", as it kept many Depression-era workers employed.

Operations

In 2010, the average daily traffic included 204 trains, 160,435 vehicles and 1650 bicycles.

Images for kids

-

Francis de Groot declares the bridge open

-

The roadway of the bridge, from the southern or city approach. From left: walkway, eight traffic lanes (the two leftmost once carried the Sydney trams), two railway tracks, and cycleway. The gantries with lights controlling traffic tidal flow are clearly visible, while the tollbooths can be seen near the bases of the high-rise buildings

See also

In Spanish: Puente de la bahía de Sídney para niños

In Spanish: Puente de la bahía de Sídney para niños