Thaddeus Stevens facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Thaddeus Stevens

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Pennsylvania |

|

| In office March 4, 1859 – August 11, 1868 |

|

| Preceded by | Anthony Roberts |

| Succeeded by | Oliver Dickey |

| Constituency | 9th district |

| In office March 4, 1849 – March 3, 1853 |

|

| Preceded by | John Strohm |

| Succeeded by | Henry A. Muhlenberg |

| Constituency | 8th district |

| Chair of the House Ways and Means Committee | |

| In office March 4, 1861 – March 3, 1865 |

|

| Preceded by | John Sherman |

| Succeeded by | Justin Smith Morrill |

| Chair of the House Appropriations Committee | |

| In office December 11, 1865 – August 11, 1868 |

|

| Preceded by | Position established |

| Succeeded by | Elihu B. Washburne |

| Personal details | |

| Born | April 4, 1792 Danville, Vermont, U.S. |

| Died | August 11, 1868 (aged 76) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Political party | Federalist (before 1828) Anti-Masonic (1828–1838) Whig (1838–1853) Know Nothing (1853–1855) Republican (1855–1868) |

| Domestic partner | Lydia Hamilton Smith (1848–1868) |

| Education | University of Vermont Dartmouth College (BA) |

| Signature | |

| Nicknames | The Old Commoner The Great Commoner |

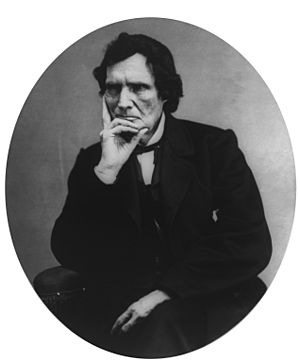

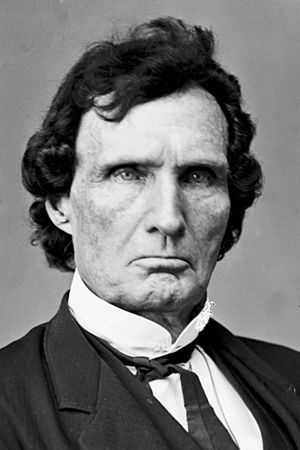

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792 – August 11, 1868) was a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s. A fierce opponent of slavery and discrimination against black Americans, Stevens sought to secure their rights during Reconstruction, leading the opposition to U.S. President Andrew Johnson. As chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee during the American Civil War, he played a leading role, focusing his attention on defeating the Confederacy, financing the war with new taxes and borrowing, crushing the power of slave owners, ending slavery, and securing equal rights for the freedmen.

Contents

Early life and education

Stevens was born in Danville, Vermont, on April 4, 1792. He was the second of four children, all boys, and was named to honor the Polish general who served in the American Revolution, Thaddeus Kościuszko. His parents were Baptists who had emigrated from Massachusetts around 1786. Thaddeus was born with a club foot which, at the time, was seen by some as a judgment from God for secret parental sin. His older brother was born with the same condition in both feet. The boys' father, Joshua Stevens, was a farmer and cobbler who struggled to make a living in Vermont. After fathering two more sons (born without disability), Joshua abandoned the children and his wife Sarah (née Morrill). The circumstances of his departure and his subsequent fate are uncertain; he may have died at the Battle of Oswego during the War of 1812.

Sarah Stevens struggled to make a living from the farm even with the increasing aid of her sons. She was determined that her sons improve themselves, and in 1807 moved the family to the neighboring town of Peacham, Vermont, where she enrolled young Thaddeus in the Caledonia Grammar School (often called the Peacham Academy). He suffered much from the taunts of his classmates for his disability. Later accounts describe him as "wilful, headstrong" with "an overwhelming burning desire to secure an education."

After graduation, he enrolled at the University of Vermont, but suspended his studies due to the federal government's appropriation of campus buildings during the War of 1812. Stevens then enrolled in the sophomore class at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire. At Dartmouth, despite a stellar academic career, he was not elected to Phi Beta Kappa; this was reportedly a scarring experience for him.

Stevens graduated from Dartmouth in 1814 and was chosen as a speaker at the commencement ceremony. Afterward, he returned to Peacham and briefly taught there. Stevens also began to read law in the office of John Mattocks. In early 1815, correspondence with a friend Samuel Merrill, a fellow Vermonter who had moved to York, Pennsylvania to become preceptor of the York Academy, led to an offer for Stevens to join the academy faculty. He moved to York to teach, and continued the study of law in the offices of David Cossett.

Career

Stevens moved to Pennsylvania as a young man and quickly became a successful lawyer in Gettysburg. He interested himself in municipal affairs and then in politics. He was an active leader of the Anti-Masonic Party, as a fervent believer that Freemasonry in the United States was an evil conspiracy to secretly control the republican system of government. He was elected to the Pennsylvania House of Representatives, where he became a strong advocate of free public education. Financial setbacks in 1842 caused him to move his home and practice to the larger city of Lancaster. There, he joined the Whig Party and was elected to Congress in 1848. His activities as a lawyer and politician in opposition to slavery cost him votes, and he did not seek reelection in 1852. After a brief flirtation with the Know-Nothing Party, Stevens joined the newly formed Republican Party and was elected to Congress again in 1858. There, with fellow radicals such as Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner, he opposed the expansion of slavery and concessions to the South as the war came.

Stevens argued that slavery should not survive the war; he was frustrated by the slowness of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln to support his position. He guided the government's financial legislation through the House as Ways and Means chairman. As the war progressed towards a Northern victory, Stevens came to believe that not only should slavery be abolished, but that black Americans should be given a stake in the South's future through the confiscation of land from planters to be distributed to the freedmen. His plans went too far for the Moderate Republicans and were not enacted.

After the assassination of Abraham Lincoln in April 1865, Stevens came into conflict with the new president, Johnson, who sought rapid restoration of the seceded states without guarantees for freedmen. The difference in views caused an ongoing battle between Johnson and Congress, with Stevens leading the Radical Republicans. After gains in the 1866 election, the radicals took control of Reconstruction away from Johnson. Stevens's last great battle was to secure in the House articles of impeachment against Johnson, acting as a House manager in the impeachment trial, though the Senate did not convict the President.

Historiographical views of Stevens have dramatically shifted over the years, from the early 20th-century view of Stevens as reckless and motivated by hatred of the white South to the perspective of the neoabolitionists of the 1950s and afterward, who lauded him for his commitment to equality.

American Civil War

Slavery

When the war began in April 1861, Stevens argued that the Confederates were revolutionaries to be crushed by force. He also believed that the Confederacy had placed itself beyond the protection of the U.S. Constitution by making war, and that in a reconstituted United States, slavery should have no place. Speaker Galusha Grow, whose views placed him with Stevens among the members becoming known as the Radical Republicans (for their position on slavery, as opposed to the liberal or moderate Republicans), appointed him as chairman of the House Ways and Means Committee. This position gave him power over the House's agenda.

Abolition – Yes! abolish everything on the face of the earth, but this Union; free every slave – slay every traitor – burn every rebel mansion if these things are necessary to preserve this temple of freedom to the world and to our posterity.

for his congressional seat,

September 1, 1862

In July 1861, Stevens secured the passage of an act to confiscate the property, including slaves, of certain rebels. In November 1861, Stevens introduced a resolution to emancipate all slaves; it was defeated. However, legislation did pass that abolished slavery in the District of Columbia and in the territories. By March 1862, to Stevens's exasperation, the most Lincoln had publicly supported was gradual emancipation in the Border states, with the slave owners compensated by the federal government.

Stevens and other radicals were frustrated at how slow Lincoln was to adopt their policies for emancipation; according to Brodie, "Lincoln seldom succeeded in matching Stevens's pace, though both were marching towards the same bright horizon." In April 1862, Stevens wrote to a friend, "As for future hopes, they are poor as Lincoln is nobody." The radicals aggressively pushed the issue, provoking Lincoln to comment: "Stevens, Sumner and [Massachusetts Senator Henry] Wilson simply haunt me with their importunities for a Proclamation of Emancipation. Wherever I go and whatever way I turn, they are on my tail, and still in my heart, I have the deep conviction that the hour [to issue one] has not yet come." The President stated that if it came to a showdown between the radicals and their enemies, he would have to side with Stevens and his fellows, and deemed them "the unhandiest devils in the world to deal with" but "with their faces ... set Zionwards." Although Lincoln composed his proclamation in June and July 1862, the secret was held within his Cabinet, and the President turned aside radical pleadings to issue one until after the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam in September. Stevens quickly adopted the Emancipation Proclamation for use in his successful re-election campaign. When Congress returned in December, Stevens maintained his criticism of Lincoln's policies, calling them "flagrant usurpations, deserving the condemnation of the community." Stevens generally opposed Lincoln's plans to colonize freed slaves abroad, though sometimes he supported emigration proposals for political reasons. Stevens wrote to a nephew in June 1863 saying, "The slaves ought to be incited to insurrection and give the rebels a taste of real civil war."

During the Confederate incursion into the North in mid-1863 that culminated in the Battle of Gettysburg, Confederates twice sent parties to Stevens's Caledonia Forge. Stevens, who had been there supervising operations, was hastened away by his workers against his will. General Jubal Early looted and vandalized the Forge, causing a loss to Stevens of about $80,000. Early said that the North had done the same to southern figures and that Stevens was well known for his vindictiveness towards the South.

Stevens pushed Congress to pass a constitutional amendment abolishing slavery. The Emancipation Proclamation was a wartime measure, did not apply to all slaves, and might be reversed by peacetime courts; an amendment would be slavery's end. The Thirteenth Amendment – which outlawed slavery and involuntary servitude except as a punishment for crime – easily passed the Senate but failed in the House in June; fears that it might not pass delayed a renewed attempt there. Lincoln campaigned aggressively for the amendment after his re-election in 1864, and Stevens described his December annual message to Congress as "the most important and best message that has been communicated to Congress for the last 60 years". Stevens closed the debate on the amendment on January 13, 1865. Illinois Representative Isaac Arnold wrote: "distinguished soldiers and citizens filled every available seat, to hear the eloquent old man speak on a measure that was to consummate the warfare of forty years against slavery."

The amendment passed narrowly after heavy pressure exerted by Lincoln himself, along with offers of political appointments from the "Seward lobby". Democrats made allegations of bribery; Stevens stated: "the greatest measure of the nineteenth century was passed by corruption, aided and abetted by the purest man in America." The amendment was declared ratified on December 18, 1865. Stevens continued to push for a broad interpretation of it that included economic justice in addition to the formal end of slavery.

After passing the Thirteenth Amendment, Congress debated the economic rights of the freedmen. Urged on by Stevens, it voted to authorize the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, with a mandate (though no funding) to set up schools and to distribute "not more than forty acres" [16 ha] of confiscated Confederate land to each family of freed slaves.

Financing the war

Stevens worked closely with Lincoln administration officials on legislation to finance the war. Within a day of his appointment as Ways and Means chairman, he had reported a bill for a war loan. Legislation to pay the soldiers Lincoln had already called into service and to allow the administration to borrow to prosecute the war quickly followed. These acts and more were pushed through the House by Stevens. To defeat the delaying tactics of Copperhead opponents, he had the House set debate limits as short as half a minute.

Stevens played a major part in the passage of the Legal Tender Act of 1862 when for the first time, the United States issued currency backed only by its own credit, not by gold or silver. Early makeshifts to finance the war, such as war bonds, had failed as it became clear the war would not be short. In 1863, Stevens aided the passage of the National Banking Act, which required that banks limit their currency issues to the number of federal bonds that they were required to hold. The system endured for half a century until supplanted by the Federal Reserve System in 1913.

Although the Legal Tender legislation allowed for the payment of government obligations in paper money, Stevens was unable to get the Senate to agree that interest on the national debt should be paid with greenbacks. As the value of paper money dropped, Stevens railed against gold speculators, and in June 1864, after consultation with Treasury Secretary Salmon P. Chase, proposed what became known as the Gold Bill – to abolish the gold market by forbidding its sale by brokers or for future delivery. It passed Congress in June; the chaos caused by the lack of an organized gold market caused the value of paper to drop even faster. Under heavy pressure from the business community, Congress repealed the bill on July 1, twelve days after its passage. Stevens was unrepentant even as the value of paper currency recovered in late 1864 amid the expectation of Union victory, proposing legislation to make paying a premium in greenbacks for an amount in gold coin a criminal offense. It did not pass.

Like most Pennsylvania politicians of both parties, Stevens was a major proponent of tariffs, which increased from 19% to 48% from fiscal 1861 to fiscal 1865. According to activist Ida Tarbell in "The Tariff in Our Times:" [Import] duties were never too high for [Stevens], particularly for iron, for he was a manufacturer and it was often said in Pennsylvania that the duties he advocated in no way represented the large iron interests of the state, but were hoisted to cover the needs of his own ... badly managed works."

Reconstruction

Problem of reconstructing the South

As Congress debated how the U.S. would be organized after the war, the status of freed slaves and former Confederates remained undetermined. Stevens stated that what was needed was a "radical reorganization of southern institutions, habits, and manners." Stevens, Sumner, and other radicals argued that the southern states should be treated like conquered provinces without constitutional rights. Lincoln, on the contrary, said that only individuals, not states, had rebelled. In July 1864, Stevens pushed Lincoln to sign the Wade–Davis Bill, which required at least half of prewar voters to sign an oath of loyalty for a state to gain readmission. Lincoln, who advocated his more lenient ten percent plan, pocket vetoed it.

Stevens reluctantly voted for Lincoln at the convention of the National Union Party, a coalition of Republicans and War Democrats. He would have preferred to vote for the sitting vice president, Hannibal Hamlin, as Lincoln's running mate in 1864. However, his delegation voted to cast the state's ballots for the administration's favored candidate, Military Governor of Tennessee Andrew Johnson, a War Democrat who had been a Tennessee senator and elected governor. Stevens was disgusted at Johnson's nomination, complaining, "can't you get a candidate for Vice-President without going down into a damned rebel province for one?" Stevens campaigned for the Lincoln–Johnson ticket; it was elected, as was Stevens for another term in the House. When in January 1865 Congress learned that Lincoln had attempted peace talks with Confederate leaders, an outraged Stevens declared that if the American electorate could vote again, they would elect General Benjamin Butler instead of Lincoln.

Presidential Reconstruction

In May 1865, Andrew Johnson began what came to be known as "Presidential Reconstruction": recognizing a provisional government of Virginia led by Francis Harrison Pierpont, calling for other former rebel states to organize constitutional conventions, declaring amnesty for many southerners, and issuing individual pardons to even more. Johnson did not push the states to protect the rights of freed slaves, and immediately began to counteract the land reform policies of the Freedmen's Bureau. These actions outraged Stevens and others who took his view. The radicals saw that freedmen in the South risked losing the economic and political liberty necessary to sustain emancipation from slavery. They began to call for universal male suffrage and continued their demands for land reform.

Stevens wrote to Johnson that his policies were gravely damaging the country and that he should call a special session of Congress, which was not scheduled to meet until December. When his communications were ignored, Stevens began to discuss with other radicals how to prevail over Johnson when the two houses convened. Congress has the constitutional power to judge whether those seeking to be its members are properly elected; Stevens urged that no senators or representatives from the South be seated. He argued that the states should not be readmitted as thereafter Congress would lack the power to force race reform.

In September, Stevens gave a widely reprinted speech in Lancaster in which he set forth what he wanted for the South. He proposed that the government confiscate the estates of the largest 70,000 landholders there, those who owned more than 200 acres (81 ha). Much of this property he wanted distributed in plots of 40 acres (16 ha) to the freedmen; other lands would go to reward loyalists both North and South, or to meet government obligations. He warned that under the President's plan, the southern states would send rebels to Congress who would join with northern Democrats and Johnson to govern the nation and perhaps undo emancipation.

Through late 1865, the southern states held white-only balloting and, in congressional elections, chose many former rebels, most prominently Confederate Vice President Alexander Stephens, voted as senator by the Georgia Legislature. Violence against African-Americans was common and unpunished in the South; the new legislatures enacted Black Codes, depriving the freedmen of most civil rights. These actions, seen as provocative in the North, both privately dismayed Johnson and helped turn northern public opinion against the president. Stevens proclaimed that "This is not a 'white man's Government'! ... To say so is political blasphemy, for it violates the fundamental principles of our gospel of liberty."

Congressional Reconstruction

In 1865, Stevens took the post of Chairman of the House Committee on Appropriations, retaining control over the House's agenda. Stevens focused on legislation that would secure the freedom promised by the newly ratified Thirteenth Amendment. He proposed and then co-chaired the Joint Committee on Reconstruction with Maine Senator William Pitt Fessenden. This body, also called the Committee of Fifteen, investigated conditions in the South. It heard not only of the violence against African-Americans but against Union loyalists and against what southerners termed "carpetbaggers". Northerners who had journeyed south after the restoration of peace.

The Committee of Fifteen began to consider what would become the Fourteenth Amendment. Stevens had begun drafting versions in December 1865, before the Committee had even formed. In January 1866, a subcommittee including Stevens and John Bingham proposed two amendments: one giving Congress the unqualified power to secure equal rights, privileges, and protections for all citizens; the other explicitly annulling all racially discriminatory laws. Stevens believed that the Declaration of Independence and Organic Acts already bound the federal government to these principles, but that an amendment was necessary to allow enforcement against discrimination at the state level. The resolution providing for what would become the Fourteenth Amendment was watered down in Congress; during the closing debate, Stevens said these changes had shattered his lifelong dream in equality for all Americans. Nevertheless, stating that he lived among men, not angels, he supported the passage of the compromise amendment. Still, Stevens told the House: "Forty acres of land and a hut would be more valuable to [the African-American] than the immediate right to vote."

When Illinois Senator Lyman Trumbull introduced legislation to reauthorize and expand the Freedmen's Bureau, Stevens called the bill a "robbery" because it did not include sufficient provisions for land reform or protect the property of refugees given them by the military occupation of the South. Johnson vetoed the bill anyway, calling the Freedmen's Bureau unconstitutional, and decrying its cost: Congress had never purchased land, established schools, or provided financial help for "our own people." Congress was unable to override Johnson's veto in February, but five months later passed a similar bill. Stevens criticized the passage of the Southern Homestead Act of 1866, arguing that the low-quality land it made available would not drive real economic growth for black families.

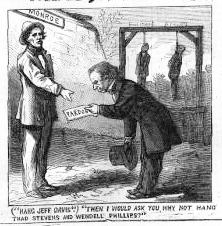

Congress overrode a Johnson veto to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1866 (also introduced by Trumbull), granting African-Americans citizenship and equality before the law and forbidding any action by a state to the contrary. Johnson made the gap between him and Congress wider when he accused Stevens, Sumner, and Wendell Phillips of trying to destroy the government.

After Congress adjourned in July, the campaigning for the fall elections began. Johnson embarked on a trip by rail, dubbed the "Swing Around the Circle" that won him few supporters; his arguments with hecklers were deemed undignified. He attacked Stevens and other radicals during this tour. Stevens campaigned for firm measures against the South, his hand strengthened by violence in Memphis and New Orleans, where African-Americans and white Unionists had been attacked by mobs, including the police. Stevens was returned to Congress by his constituents; Republicans would have a two-thirds majority in both houses in the next Congress.

Radical Reconstruction

In January 1867, Stevens introduced legislation to divide the South into five districts, each commanded by an army general empowered to override civil authorities. These military officers were to supervise elections with all males of whatever race, entitled to vote, except for those who could not take an oath of past loyalty – most white Southerners could not. The states were to write new constitutions (subject to approval by Congress) and hold elections for state officials. Only if a state ratified the Fourteenth Amendment would its delegation be seated in Congress. The system gave power to a Republican coalition of freedmen (mobilized by the Union League), carpetbaggers, and co-operative Southerners (the last dubbed scalawags by indignant ex-rebels) in most southern states. These states ratified the Fourteenth Amendment, which became part of the Constitution in mid-1868.

Stevens steered a bill to enfranchise African-Americans in the District of Columbia through the House. The Senate passed it in 1867, and it was enacted over Johnson's veto. Congress was downsizing the Army for peacetime; Stevens offered an amendment, which became part of the bill as enacted, to have two regiments of African-American cavalry. His solicitude for African-Americans extended to the Native American; Stevens was successful in defeating a bill to place reservations under state law, noting that the native people had often been abused by the states. An expansionist, he supported the railroads. He added a stipulation into the [Transcontinental] Pacific Railroad Act requiring the applicable railroads to buy iron "of American manufacture" of the top price qualities. Although he sought to protect manufacturers with high tariffs, he also sought unsuccessfully to get a bill passed to protect labor with an eight-hour day in the District of Columbia. Stevens advocated a bill to give government workers raises; it did not pass.

Final months and death

Thaddeus Stevens died on the night of August 11, 1868.

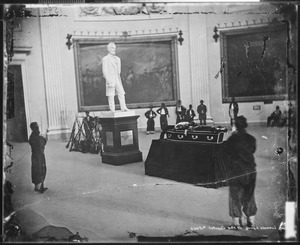

President Johnson issued no statement upon the death of his enemy. Stevens's body was conveyed from his house to the Capitol by white and black pallbearers together. Thousands of mourners, of both races, filed past his casket as he lay in state at the United States Capitol rotunda; Stevens was the third man, after Clay and Lincoln, to receive that honor. African-American soldiers constituted the guard of honor. After a service there, his body was taken by funeral train to Lancaster, a city draped in black for the funeral. Stevens was laid to rest in Shreiner's Cemetery (today the Shreiner-Concord Cemetery); it allowed the burial of people of all races, although, at the time of Stevens's interment, only one African-American was buried there. The people of his district posthumously renominated him to Congress. They elected his former student Oliver J. Dickey to succeed him. When Congress convened in December 1868, there were several speeches in tribute to Stevens; they were afterward collected in book form.

Personal life

Stevens never married, though there were rumors about his twenty-year relationship (1848–1868) with his widowed housekeeper, Lydia Hamilton Smith (1813–1884). She was a light-skinned African-American.

When Stevens died, Smith was at his bedside, along with his friend Simon Stevens, nephew Thaddeus Stevens Jr., two African-American nuns, and several other individuals. Under Stevens's will, Smith was allowed to choose between a lump sum of $5,000 or a $500 annual allowance; she could also take any furniture in his house. With the inheritance, she purchased Stevens's house, where she had lived for many years. A Roman Catholic, she chose to be buried in a Catholic cemetery, not near Stevens, although she left money for the upkeep of his grave.

Stevens had taken custody of his two young nephews, Thaddeus (often called "Thaddeus Jr.") and Alanson Joshua Stevens, after their parents died in Vermont. A

Buildings associated with Stevens and with Smith in Lancaster are being renovated by the local historical society, LancasterHistory.org.

Schools named after Stevens include Thaddeus Stevens Elementary School in Washington, D.C., founded in 1868 as the first school built for African-American children there. It was segregated for the first 86 years of its existence. In 1977, Amy Carter, daughter of President Jimmy Carter, a Georgian, was enrolled there, the first child of a sitting president to attend public school in almost 70 years.

Stevens was celebrated for his wit and sarcasm. When Lincoln questioned whether Pennsylvania Republican leader Simon Cameron, who was frequently accused of corruption, was a thief, Stevens was said to have replied, "I don't think he would steal a red-hot stove." When Cameron allegedly heard about and objected to this characterization, Stevens is supposed to have told Lincoln "I believe I told you he would not steal a red hot stove. I will now take that back." Stevens's ill-fitting wigs were a well-known topic of discussion in Washington, but when a female admirer who apparently did not know asked for a lock of Stevens's hair as a keepsake, he removed his hairpiece, held it out to her, and invited her to take any curl she found acceptable.

Steven Spielberg's 2012 film Lincoln, in which Stevens was portrayed by Tommy Lee Jones, brought new public interest in Stevens. Jones's character is portrayed as the central figure among the radicals, responsible in large part for the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment.

On April 2, 2022, in front of the Adams County Courthouse in Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, a statue of Stevens was unveiled as part of a celebration of Stevens' 230th birthday. The statue was commissioned by the Thaddeus Stevens Society and was sculpted by multidisciplinary artist Alex Paul Loza.

See also

In Spanish: Thaddeus Stevens para niños

In Spanish: Thaddeus Stevens para niños

Images for kids

-

Color print of a Harper's Weekly woodcut by Theodore R. Davis depicting Stevens making his final argument to the House during March 2, 1868 debate on the articles of impeachment

-

Illustration from Harper's Weeklyof Stevens (right) and John A. Bingham formally notifying the Senate of Johnson's impeachment

-

Johnson impeachment managersSeated L-R: Benjamin Butler, Stevens, Thomas Williams, John Bingham;Standing L-R: James F. Wilson, George S. Boutwell, John A. Logan