Theodora (wife of Justinian I) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Theodora |

|

|---|---|

| Augusta | |

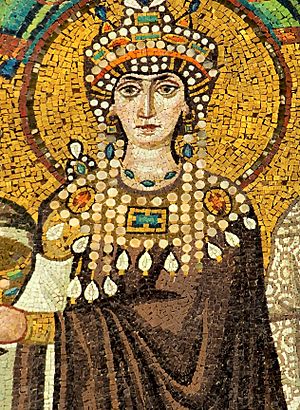

Depiction from a contemporary portrait mosaic in the Basilica of San Vitale, Ravenna

|

|

| Byzantine empress | |

| Tenure | 1 April 527 – 28 June 548 |

| Born | c. 500 |

| Died | 28 June 548 (aged 48) Constantinople, Byzantine Empire |

| Burial | Church of the Holy Apostles |

| Spouse | Justinian I |

| Dynasty | Justinian |

| Religion | Christianity (Miaphysitism) |

Theodora ( Greek: Θεοδώρα; c. 500 – 28 June 548) was an Eastern Roman empress by marriage to emperor Justinian. She became empress upon Justinian's accession in 527 and was one of his chief advisers, albeit from humble origins. Along with her spouse, Theodora is a saint in the Eastern Orthodox Church and in the Oriental Orthodox Church, commemorated on 14 November and 28 June respectively.

Contents

Early years

Much of Theodora's early life is unknown. She was born c. AD 500. Her father, Acacius, was a bear trainer of the hippodrome's Green faction in Constantinople. Her mother, whose name is not recorded, was a dancer and an actress. Her parents had two more daughters, the eldest named Comito and the youngest Anastasia. After her father's death, her mother remarried quickly, but the family was extremely poor.

From an early age, Theodora performed on stage.

Later, Theodora traveled to Alexandria, Egypt, where some historians speculate that she met Patriarch Timothy III, a Miaphysite, and converted to Miaphysite Christianity. Afterwards, Theodora returned to Constantinople. There, she met Justinian.

Justinian sought to marry Theodora, though he was prevented from doing so by a Roman law from Constantine's time that barred anyone of senatorial rank from marrying actresses. The empress Euphemia, consort of the emperor Justin, also strongly opposed the marriage. Following Euphemia's death in 524, Justin passed a new law stating that reformed actresses could marry outside of their rank if the marriage was approved by the emperor. Shortly thereafter, Justinian married Theodora.

Empress

When Justinian succeeded to the throne in 527, two years after the marriage, Theodora was crowned augusta and became empress of the Eastern Roman Empire. According to Procopius, she shared in his decisions, plans and political strategies, participated in state councils, and had great influence over him.

As Justinian's partner, Theodora shared Justinian's vision of the Byzantine Empire. His vision was straightforward – there could be no Roman Empire that didn't include Rome within its control. Since childhood, he was taught that there was one God and, therefore to him one legitimate Empire. Due to being the only Christian Emperor and Empress, they believed it was their role to duplicate the heavenly structure on Earth. Being relatively young as an Emperor and Empress, compared to their recent predecessors, neither Justinian nor Theodora were content to maintaining the status quo. Their goals and projects, whether it be building new churches and public buildings or raising troops for expansive military campaigns, would require a large amount of funding. Justinian and his chief financial minister, John the Cappadocian, ruthlessly pursued additional taxes from the aristocracy who bristled at the lack of respect for their patrician status.

The Nika riots

Two major party factions were at odds before, during, and after Justinian and Theodora's reign – the Blues and the Greens. Street violence between the parties was a regular event and when Justinian became emperor, he staked out a claim to drive the city to a more lawful and orderly community. During a riot between the two factions in early January 532.

The rioters set many public buildings on fire, and proclaimed a new emperor, Hypatius, the nephew of former emperor Anastasius I. Unable to control the mob, Justinian and his officials prepared to flee. According to Procopius, at a meeting of the government council, Theodora spoke out against leaving the palace and underlined the significance of someone who died as a ruler instead of living as an exile or in hiding.

Her determined speech motivated Justinian who had been preparing to flee. Afterwards Justinian ordered his loyal troops, led by the officers, Belisarius and Mundus, to attack the demonstrators in the Hippodrome, killing over 30,000 civilian rebels. Other reports claimed greater numbers of victims. Hypatius was also put to death by Justinian. In one source, this came at Theodora's insistence.

Later life

Following the Nika revolt, Justinian and Theodora rebuilt Constantinople, including aqueducts, bridges and more than twenty-five churches, the most famous of which is Hagia Sophia. Justinian and Theodora also recognized the danger of allowing the level of dissent to grow throughout the empire as a result of the actions of their reign that impacted the common people. Although, they soon felt secure enough to reinstate the two ministers that were dismissed to appease the rebels; John the Cappadocian as financial minister, Tribonian as the primary legal minister. The couple monitored their administration's actions more carefully to ensure that their activities were more reasonable in their impact on the common citizenry. Justinian and Theodora retained a distaste for the aristocrats that had attempted to unseat them. In retaliation against their disloyalty, the 19 senators that participated in the attempted Nika coup were executed and had their estates destroyed. Those who remained were left to deal with the aggressive taxation and other wealth capture schemes that John the Cappadocian hatched to continue funding Justinian and Theodora's aggressive rebuilding plans.

Justinian and Theodora's legislations also expanded the rights of women in divorce and property ownership and gave mothers some guardianship rights over their children.

Religious policy

| Saint Theodora | |

|---|---|

Empress Theodora and attendants (mosaic from Basilica of San Vitale, 6th century)

|

|

| Empress | |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church Oriental Orthodox Church |

| Major shrine | Church of the Holy Apostles, Constantinople modern day Istanbul, Turkey |

| Feast | 14 November in the Eastern Orthodox Church, 28 June in the Syriac Orthodox Church |

| Attributes | Imperial Vestment |

Since Justinian was not the recognized head of any of the sects of the Christian church, his focus was on reducing and, where possible, eliminating friction between the various Christian sects and the Empire. His perspective was that as the Christian emperor, he should be in harmony with the head(s) of The Church. Similarly, with Justinian a Chalcedonian and Theodora professing Miaphysite beliefs or at least sympathetic with the Monophysite cause, Justinian worked to heal the schism that divided the Constantinople church, from the Roman church. He sought a united Church that would “partner” with the one Emperor (himself). The Emperor would manage human affairs and the priesthood would manage the divine affairs of God. Since the Emperor was accountable to the law, Justinian made sure that the law recognized the Emperor as being the law incarnate – with universal authority of divine origin. Consequently, he used the law to micromanage the implementation of religion through laws aimed at its very execution.

Theodora worked against her husband's support of Chalcedonian Christianity in the ongoing struggle for the predominance of each faction. As a result, she was accused of fostering heresy and thus undermined the unity of Christendom. However, Procopius and Evagrius Scholasticus suggested instead that Justinian and Theodora were merely pretending to be opposed to each other.

In spite of Justinian being Chalcedonian, Theodora founded a Miaphysite monastery in Sykae and provided shelter in the palace for Miaphysite leaders who faced opposition from the majority of Chalcedonian Christians, like Severus and Anthimus. Anthimus had been appointed Patriarch of Constantinople under her influence, and after the excommunication order he was hidden in Theodora's quarters for twelve years, until her death. When the Chalcedonian Patriarch Ephraim provoked a violent revolt in Antioch, eight Miaphysite bishops were invited to Constantinople and Theodora welcomed them and housed them in the Hormisdas Palace adjoining the Great Palace, which had been Justinian and Theodora's own dwelling before they became Emperor and Empress.

In Egypt, when Timothy III died, Theodora enlisted the help of Dioscoros, the Augustal Prefect, and Aristomachos the duke of Egypt, to facilitate the enthronement of a disciple of Severus, Theodosius, thereby outmaneuvering her husband, who had intended a Chalcedonian successor. Pope Theodosius I of Alexandria, even with the help of imperial troops, could not hold his ground in Alexandria against Justinian's Chalcedonian followers and he was exiled by Justinian along with 300 Miaphysites into the fortress of Delcus in Thrace.

When Pope Silverius refused Theodora's demand that he remove the anathema of Pope Agapetus I from Patriarch Anthimus, she sent Belisarius instructions to find a pretext to remove Silverius. When this was accomplished, Pope Vigilius was appointed in his stead.

In Nobatae, south of Egypt, the inhabitants were converted to Miaphysite Christianity about 540. Justinian had been determined that they be converted to the Chalcedonian faith and Theodora equally determined that they should be Miaphysites. Justinian made arrangements for Chalcedonian missionaries from Thebaid to go with presents to Silko, the king of the Nobatae. On hearing this, Theodora prepared her own missionaries and wrote to the Duke of Thebaid that he should delay her husband's embassy, so that the Miaphysite missionaries would arrive first. The duke was canny enough to thwart the easy going Justinian instead of the unforgiving Theodora. He saw to it that the Chalcedonian missionaries were delayed and when they eventually reached Silko, they were sent away. The Nobatae had then already adopted the Miaphysite creed of Theodosius.

Death

Theodora's death is recorded by Victor of Tonnena, with the cause uncertain but the Greek terms used are often translated as "cancer". The date was 28 June 548 at the age of 48, although other sources report that she died at 51. Later accounts frequently attribute the death to specifically breast cancer, although it was not identified as such in the original report, in which the use of the term "cancer" probably referred to a more general "suppurating ulcer or malignant tumor". Her body was buried in the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople. During a procession in 559, Justinian visited and lit candles for her tomb.

Historiography

The main historical sources for her life are the works of her contemporary Procopius. Procopius was a member of the staff of Belisarius, a field marshal for Justinian, who is perhaps the best-known officer of Justinian's officers largely because of Procopius's writings. The historian offered three different portrayals of the Empress. The Wars of Justinian, largely completed in 545, paints a picture of a courageous woman who helped save Justinian's attempt at the throne.

Later, he wrote the Secret History. The work has sometimes been interpreted as representing a deep disillusionment with the Emperor Justinian, the empress, and even his patron Belisarius.

Procopius' Buildings of Justinian, written probably after Secret History, is a panegyric that paints Justinian and Theodora as a pious couple and presents particularly flattering portrayals of them. Besides her piety, her beauty is also praised. It is important to note, however, that Theodora had already died when the work was published, meanwhile Justinian was still alive and most likely commissioned the work.

Her contemporary John of Ephesus writes about Theodora in his Lives of the Eastern Saints. Theophanes the Confessor mentions some familial relations of Theodora to figures not mentioned by Procopius. Victor Tonnennensis notes her familial relation to the next empress, Sophia.

Michael the Syrian, the Chronicle of 1234 and Bar-Hebraeus place her origin in the city of Daman, near Kallinikos, Syria. They make an alternate account compared to Procopius by making Theodora the daughter of a priest, trained in the pious practices of Miaphysitism since birth. These are late Miaphysite sources. The Miaphysites have a tendency to regard Theodora as one of their own. Their account is also an alternative to what is told by the contemporary John of Ephesus. Many modern scholars prefer Procopius' account.

Lasting influence

The Miaphysites believed her influence on Justinian to be so strong that after her death, when he worked to bring harmony between the Miaphysites and the Chalcedonian Christians in the Empire and kept his promise to protect her little community of Miaphysite refugees in the Hormisdas Palace, the Miaphysites suspected Theodora's memory to be the driving factor. Theodora provided much political support for the ministry of Jacob Baradaeus, and apparently personal friendship as well. Diehl attributes the modern existence of Jacobite Christianity equally to Baradaeus and to Theodora.

Olbia in Cyrenaica renamed itself Theodorias after Theodora. (It was a common event that ancient cities renamed themselves to honor an Emperor or Empress.) The city, now called Qasr Libya, is known for its splendid sixth-century mosaics.

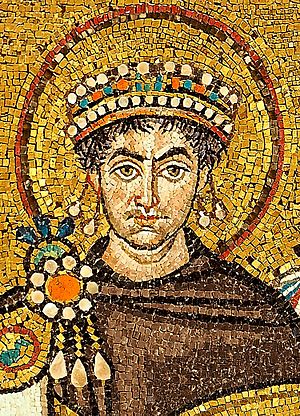

Theodora and Justinian are represented in mosaics that exist to this day in the Basilica of San Vitale of Ravenna, Italy, which were completed a year before her death after 547 when the Byzantines retook the city. She is depicted in full imperial garb, endowed with jewels befitting her role as empress. Her cloak is embroidered with imagery of the three kings bearing their gifts for the Christ child, symbolizing a connection with her and Justinian bringing gifts to the church. In this case, she is shown bearing a communion chalice. In addition to the religious tone of these mosaics, other mosaics depict Theodora and Justinian receiving the vanquished kings of the Goths and Vandals as prisoners of war, surrounded by the cheering Roman Senate. The Emperor and Empress are recognized in both victory and in generosity in these large-scale public works.

Media portrayals

Art

- The artwork The Dinner Party features a place setting for Theodora.

Saint Mathurin exorcising the Empress Theodora, Abbey Saint-Ouen in Rouen

Film

- Teodora imperatrice di Bisanzio (Short, 1909) aka Theodora, Empress of Byzantium. Directed by Ernesto Maria Pasquali.

- Teodora, imperatrice di Bisanzio (1954) aka Theodora, Slave Empress. Directed by Riccardo Freda. Theodora played by Gianna Maria Canale.

- Kampf um Rom (1968) directed by Robert Siodmak, Sergiu Nicolaescu and Andrew Marton. In this movie she is played by Sylva Koscina.

- Primary Russia (1985) directed by Gennady Vasilyev. Theodora played by Margarita Terekhova

Theater

- Theodora, a Drama (1884), a play by Victorien Sardou.

Music

- The progressive rock band Big Big Train sings of Theodora herself, and the mosaics of Theodora and Justinian in Ravenna, in the song "Theodora in Green and Gold" on their 2019 album Grand Tour.

- George Frideric Handel's oratorio "Theodora" does not refer to the empress.

See also

In Spanish: Teodora para niños

In Spanish: Teodora para niños