Thomas Babington Macaulay facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

The Lord Macaulay

|

|

|---|---|

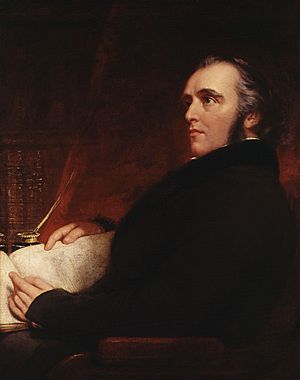

Photogravure of Macaulay by Antoine Claudet

|

|

| Secretary at War | |

| In office 27 September 1839 – 30 August 1841 |

|

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Prime Minister | The Viscount Melbourne |

| Preceded by | Viscount Howick |

| Succeeded by | Sir Henry Hardinge |

| Paymaster-General | |

| In office 7 July 1846 – 8 May 1848 |

|

| Monarch | Victoria |

| Prime Minister | Lord John Russell |

| Preceded by | Hon. Bingham Baring |

| Succeeded by | The Earl Granville |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 25 October 1800 Leicestershire, England |

| Died | 28 December 1859 (aged 59) London, England |

| Political party | Whig |

| Alma mater | Trinity College, Cambridge |

| Occupation | Politician |

| Profession | Historian |

| Signature | |

Thomas Babington Macaulay, 1st Baron Macaulay, PC, FRS, FRSE (/ˈbæbɪŋtən məˈkɔːli/; 25 October 1800 – 28 December 1859) was a British historian and Whig politician, who served as the Secretary at War between 1839 and 1841, and as the Paymaster-General between 1846 and 1848.

Macaulay's The History of England, which expressed his contention of the superiority of the Western European culture and of the inevitability of its sociopolitical progress, is a seminal example of Whig history that remains commended for its prose style.

Contents

Early life

Macaulay was born at Rothley Temple in Leicestershire on 25 October 1800, the son of Zachary Macaulay, a Scottish Highlander, who became a colonial governor and abolitionist, and Selina Mills of Bristol, a former pupil of Hannah More. They named their first child after his uncle Thomas Babington, a Leicestershire landowner and politician, who had married Zachary's sister Jean. The young Macaulay was noted as a child prodigy; as a toddler, gazing out of the window from his cot at the chimneys of a local factory, he is reputed to have asked his father whether the smoke came from the fires of hell.

He was educated at a private school in Hertfordshire, and, subsequently, at Trinity College, Cambridge, where he won several prizes, including the Chancellor's Gold Medal in June 1821, and where he in 1825 published a prominent essay on Milton in the Edinburgh Review. Macaulay did not whilst at Cambridge study classical literature, which he subsequently read in India. He in his letters describes his reading of the Aeneid whilst he was in Malvern in 1851, when he says he was moved to tears by Virgil's poetry. He taught himself German, Dutch and Spanish, and was fluent in French. He studied law and he was in 1826 called to the bar, before he took more interest in a political career. Macaulay in the Edinburgh Review in 1827, and in a series of anonymous letters to The Morning Chronicle, censured the analysis of indentured labour by the British Colonial Office expert Colonel Thomas Moody, Kt. Macaulay's evangelical Whig father Zachary Macaulay, who desired a 'free black peasantry' rather than equality for Africans, also censured, in the Anti-Slavery Reporter, Moody's contentions.

Macaulay, who did not marry nor have children, was rumoured to have fallen in love with Maria Kinnaird, who was the wealthy ward of Richard 'Conversation' Sharp. Macaulay's strongest emotional relationships were with his youngest sisters: Margaret, who died while he was in India, and Hannah, to whose daughter Margaret, whom he called 'Baba', he was also attached.

India (1834–1838)

Macaulay in 1830 accepted the invitation of Marquess of Lansdowne that he become Member of Parliament for the pocket borough of Calne. Macaulay's maiden speech in Parliament advocated abolition of the civil disabilities of the Jews in the UK. Macaulay's subsequent speeches in favour of parliamentary reform were commended. He became MP for Leeds subsequent to the 1833 enactment of the Reform Act 1832, by which Calne's representation was reduced from two MPs to one, and by which Leeds, which had not been represented before, had two MPs. Macaulay remained grateful to his former patron, Lansdowne, who remained his friend.

Macaulay was Secretary to the Board of Control under Lord Grey from 1832 until he in 1833 required, as a consequence of the penury of his father, a more remunerative office, than that of the unremunerated office of an MP, from which he resigned after the passing of the Government of India Act 1833 to accept an appointment as first Law Member of the Governor-General's Council. Macaulay in 1834 went to India, where he served on the Supreme Council between 1834 and 1838. His Minute on Indian Education of February 1835 was primarily responsible for the introduction of Western institutional education to India.

Macaulay recommended the introduction of the English language as the official language of secondary education instruction in all schools where there had been none before, and the training of English-speaking Indians as teachers. Macaulay's Minute on Indian Education contended that "a single shelf of a good European library was worth the whole native literature of India and Arabia. Honours might be roughly even in works of the imagination, such as poetry, but when we pass from works of imagination to works in which facts are recorded, and general principles investigated, the superiority of the Europeans becomes absolutely immeasurable". In his Minute on Indian Education of February 1835, Macaulay urged Lord William Bentinck, the Governor-General to reform secondary education on utilitarian lines to deliver "useful learning" – a phrase that to Macaulay was synonymous with Western culture. There was no tradition of secondary education in vernacular languages; the institutions then supported by the East India Company taught either in Sanskrit or Persian. Hence, he argued, "We have to educate a people who cannot at present be educated by means of their mother-tongue. We must teach them some foreign language." Macaulay argued that Sanskrit and Persian were no more accessible than English to the speakers of the Indian vernacular languages and existing Sanskrit and Persian texts were of little use for 'useful learning'.

Hence, from the sixth year of schooling onwards, instruction should be in European learning, with English as the medium of instruction.

Macaulay's minute largely coincided with Bentinck's views and Bentinck's English Education Act 1835 closely matched Macaulay's recommendations (in 1836, a school named La Martinière, founded by Major General Claude Martin, had one of its houses named after him), but subsequent Governors-General took a more conciliatory approach to existing Indian education.

His final years in India were devoted to the creation of a Penal Code, as the leading member of the Law Commission. In the aftermath of the Indian Mutiny of 1857, Macaulay's criminal law proposal was enacted. The Indian Penal Code in 1860 was followed by the Criminal Procedure Code in 1872 and the Civil Procedure Code in 1908. The Indian Penal Code inspired counterparts in most other British colonies, and to date many of these laws are still in effect in places as far apart as Pakistan, Malaysia, Myanmar, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka, Nigeria and Zimbabwe, as well as in India itself. This includes Section 377 of the Indian Penal Code, which remains the basis for laws which criminalize homosexuality in several Commonwealth nations.

In Indian culture, the term "Macaulay's Children" is sometimes used to refer to people born of Indian ancestry who adopt Western culture as a lifestyle, or display attitudes influenced by colonialism ("Macaulayism") – expressions used disparagingly, and with the implication of disloyalty to one's country and one's heritage. In independent India, Macaulay's idea of the civilising mission has been used by Dalitists, in particular by neo-liberalist Chandra Bhan Prasad, as a "creative appropriation for self-empowerment", based on the view that the Dalit community was empowered by Macaulay's deprecation of Hindu culture and support for Western-style education in India.

Domenico Losurdo states that "Macaulay acknowledged that the English colonists in India behaved like Spartans confronting helots: we are dealing with 'a race of sovereign' or a 'sovereign caste', wielding absolute power over its 'serfs'." Losurdo noted that this did not prompt any doubts from Macaulay over the right of Britain to administer its colonies in an autocratic fashion; for example, while Macaulay described the administration of governor-general of India Warren Hastings as being so despotic that "all the injustice of former oppressors, Asiatic and European, appeared as a blessing", he (Hastings) deserved "high admiration" and a rank among "the most remarkable men in our history" for "having saved England and civilisation".

Return to British public life (1838–1857)

Returning to Britain in 1838, he became MP for Edinburgh in the following year. He was made Secretary at War in 1839 by Lord Melbourne and was sworn of the Privy Council the same year. In 1841 Macaulay addressed the issue of copyright law. Macaulay's position, slightly modified, became the basis of copyright law in the English-speaking world for many decades. Macaulay argued that copyright is a monopoly and as such has generally negative effects on society. After the fall of Melbourne's government in 1841 Macaulay devoted more time to literary work, and returned to office as Paymaster-General in 1846 in Lord John Russell's administration.

In the election of 1847 he lost his seat in Edinburgh. He attributed the loss to the anger of religious zealots over his speech in favour of expanding the annual government grant to Maynooth College in Ireland, which trained young men for the Catholic priesthood; some observers also attributed his loss to his neglect of local issues. In 1849 he was elected Rector of the University of Glasgow, a position with no administrative duties, often awarded by the students to men of political or literary fame. He also received the freedom of the city.

In 1852, the voters of Edinburgh offered to re-elect him to Parliament. He accepted on the express condition that he need not campaign and would not pledge himself to a position on any political issue. Remarkably, he was elected on those terms. He seldom attended the House due to ill health. His weakness after suffering a heart attack caused him to postpone for several months making his speech of thanks to the Edinburgh voters. He resigned his seat in January 1856. In 1857 he was raised to the peerage as Baron Macaulay, of Rothley in the County of Leicester, but seldom attended the House of Lords.

Later life (1857–1859)

Macaulay sat on the committee to decide on the historical subjects to be painted in the new Palace of Westminster. The need to collect reliable portraits of notable figures from history for this project led to the foundation of the National Portrait Gallery, which was formally established on 2 December 1856. Macaulay was amongst its founding trustees and is honoured with one of only three busts above the main entrance.

During his later years his health made work increasingly difficult for him. He died of a heart attack on 28 December 1859, aged 59, leaving his major work, The History of England from the Accession of James the Second incomplete. On 9 January 1860 he was buried in Westminster Abbey, in Poets' Corner, near a statue of Addison. As he had no children, his peerage became extinct on his death.

Macaulay's nephew, Sir George Trevelyan, Bt, wrote the "Life and Letters" of his uncle. His great-nephew was the Cambridge historian G. M. Trevelyan.

Literary works

As a young man he composed the ballads Ivry and The Armada, which he later included as part of Lays of Ancient Rome, a series of very popular poems about heroic episodes in Roman history which he began composing in India and continued in Rome, finally publishing in 1842. The most famous of them, Horatius, concerns the heroism of Horatius Cocles. It contains the oft-quoted lines:

Then out spake brave Horatius,

The Captain of the Gate:

"To every man upon this earth

Death cometh soon or late.

And how can man die better

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his fathers,

And the temples of his gods?"

His essays, originally published in the Edinburgh Review, were collected as Critical and Historical Essays in 1843.

Historian

During the 1840s, Macaulay undertook his most famous work, The History of England from the Accession of James the Second, publishing the first two volumes in 1848. At first, he had planned to bring his history down to the reign of George III. After publication of his first two volumes, his hope was to complete his work with the death of Queen Anne in 1714.

The third and fourth volumes, bringing the history to the Peace of Ryswick, were published in 1855. At his death in 1859 he was working on the fifth volume. This, bringing the History down to the death of William III, was prepared for publication by his sister, Lady Trevelyan, after his death.

Political writing

Macaulay's political writings are famous for their ringing prose and for their confident, sometimes dogmatic, emphasis on a progressive model of British history, according to which the country threw off superstition, autocracy and confusion to create a balanced constitution and a forward-looking culture combined with freedom of belief and expression. This model of human progress has been called the Whig interpretation of history. This philosophy appears most clearly in the essays Macaulay wrote for the Edinburgh Review and other publications, which were collected in book form and a steady best-seller throughout the 19th century. But it is also reflected in History; the most stirring passages in the work are those that describe the "Glorious Revolution" of 1688.

Macaulay's approach has been criticised by later historians for its one-sidedness and its complacency. Karl Marx referred to him as a 'systematic falsifier of history'. His tendency to see history as a drama led him to treat figures whose views he opposed as if they were villains, while characters he approved of were presented as heroes. Macaulay goes to considerable length, for example, to absolve his main hero William III of any responsibility for the Glencoe massacre. Winston Churchill devoted a four-volume biography of the Duke of Marlborough to rebutting Macaulay's slights on his ancestor, expressing hope "to fasten the label 'Liar' to his genteel coat-tails".

Legacy as a historian

The Liberal historian Lord Acton read Macaulay's History of England four times and later described himself as "a raw English schoolboy, primed to the brim with Whig politics" but "not Whiggism only, but Macaulay in particular that I was so full of." However, after coming under German influence Acton would later find fault in Macaulay. In 1880 Acton classed Macaulay (with Burke and Gladstone) as one "of the three greatest Liberals".

In 1888, Acton wrote that Macaulay "had done more than any writer in the literature of the world for the propagation of the Liberal faith, and he was not only the greatest, but the most representative, Englishman then living".

W. S. Gilbert described Macaulay's wit, "who wrote of Queen Anne" as part of Colonel Calverley's Act I patter song in the libretto of the 1881 operetta Patience. (This line may well have been a joke about the Colonel's pseudo-intellectual bragging, as most educated Victorians knew that Macaulay did not write of Queen Anne; the History encompasses only as far as the death of William III in 1702, who was succeeded by Anne.)

Herbert Butterfield's The Whig Interpretation of History (1931) attacked Whig history. The Dutch historian Pieter Geyl, writing in 1955, considered Macaulay's Essays as "exclusively and intolerantly English".

George Richard Potter, Professor and Head of the Department of History at the University of Sheffield from 1931 to 1965, claimed "In an age of long letters ... Macaulay's hold their own with the best".

Potter noted that Macaulay has had many critics, some of whom put forward some salient points about the deficiency of Macaulay's History but added: "The severity and the minuteness of the criticism to which the History of England has been subjected is a measure of its permanent value. It is worth every ounce of powder and shot that is fired against it." Potter concluded that "in the long roll of English historical writing from Clarendon to Trevelyan only Gibbon has surpassed him in security of reputation and certainty of immortality".

Piers Brendon wrote that Macaulay is "the only British rival to Gibbon." In 1972, J. R. Western wrote that: "Despite its age and blemishes, Macaulay's History of England has still to be superseded by a full-scale modern history of the period." In 1974 J. P. Kenyon stated that: "As is often the case, Macaulay had it exactly right."

W. A. Speck wrote in 1980, that a reason Macaulay's History of England "still commands respect is that it was based upon a prodigious amount of research".

On the other hand, Speck also wrote that Macaulay "took pains to present the virtues even of a rogue, and he painted the virtuous warts and all", and that "he was never guilty of suppressing or distorting evidence to make it support a proposition which he knew to be untrue".

Himmelfarb also laments that "the history of the History is a sad testimonial to the cultural regression of our times".

In the novel Marathon Man and its film adaptation, the protagonist was named 'Thomas Babington' after Macaulay.

In 2008, Walter Olson argued for the pre-eminence of Macaulay as a British classical liberal.

Works

- Lays of Ancient Rome originally published in the year 1842.

- Macaulay, Thomas Babington (1848).

The History of England from the Accession of James II. Philadelphia: Porter & Coates. Wikisource.

The History of England from the Accession of James II. Philadelphia: Porter & Coates. Wikisource.

- 5 vols (1848): Vol 1, Vol 2, Vol 3, Vol 4, Vol 5 at Internet Archive

- 5 vols (1848): Vol. 1, Vol. 2, Vol. 3, Vol. 4, Vol. 5 at Project Gutenberg

- volumes 1–3 at LibriVox.org

- Critical and Historical Essays(1843), 2 vols, edited by Alexander James Grieve. Vol. 1, Vol. 2

- Macaulay, Thomas Babington Baron Macaulay (1873). "Social and Industrial Capacities of the Negroes". Critical Historical and Miscellaneous Essays with a Memoir and Index. V. and VI. Mason, Baker & Pratt. https://books.google.com/books?id=F6JGAQAAMAAJ&pg=RA1-PA361.

- Macaulay, Thomas Babington Baron Macaulay (1881). Lays of Ancient Rome: With Ivry, and The Armada. Longmans, Green, and Company. https://archive.org/details/in.ernet.dli.2015.182206.

- William Pitt, Earl of Chatham: Second Essay (Maynard, Merrill, & Company, 1892, 110 pages)

- The Miscellaneous Writings and Speeches of Lord Macaulay(1860), 4 vols Vol. 1, Vol. 2, Vol. 3, Vol. 4

- Machiavelli on Niccolò Machiavelli (1850).

- The Letters of Thomas Babington Macaulay(1881), 6 vols, edited by Thomas Pinney.

- The Journals of Thomas Babington Macaulay, 5 vols, edited by William Thomas.

- Macaulay index entry at Poets' Corner

- Lays of Ancient Rome (Complete) at Poets' Corner with an introduction by Bob Blair

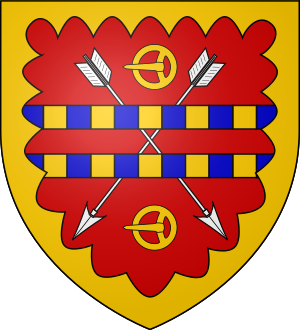

Arms

|

|

See also

In Spanish: Thomas Macaulay para niños

In Spanish: Thomas Macaulay para niños

- Philosophic Whigs

- Whig history further explains the interpretation of history that Macaulay espoused.

- Samuel Rogers#Middle life and friendships