Torreón massacre facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Torreón massacre |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Mexican Revolution | |

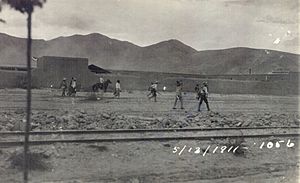

Mexican forces outside the Casino de la Laguna

|

|

| Location | Torreón, Coahuila |

| Coordinates | 25°32′22″N 103°26′55″W / 25.53944°N 103.44861°W |

| Date | 13–15 May 1911 |

| Target | Asian Mexicans |

|

Attack type

|

Massacre |

| Deaths | 303 (see Casualties, below) |

| Assailants | |

|

Number of participants

|

4,500 |

| Motive | Ethnic hatred, Sinophobia, Anti-Japanese sentiment |

The Torreón massacre (Spanish: Matanza de chinos de Torreón) was a racially motivated massacre that took place on 13–15 May 1911 in the Mexican city of Torreón, Coahuila. Over 300 Asian Mexicans were killed by a local mob and the revolutionary forces of Francisco I. Madero, mostly Cantonese Mexicans and some Japanese Mexicans. A large number of Cantonese homes and shops were looted and destroyed.

Torreón was the last major city to be taken by the Maderistas during the Mexican Revolution. When the government forces withdrew, the rebels entered the city in the early morning and, along with the local population, began a ten-hour massacre of the Cantonese community. The event touched off a diplomatic crisis between Qing China and Mexico, with the former demanding 30 million pesos in reparation. At one point it was rumored that Qing China had even dispatched a warship to Mexican waters (the cruiser Hai Chi, which was anchored in Cuba at the time). An investigation into the massacre concluded that it was an unprovoked act of racism.

Contents

Background

Cantonese immigration to Mexico began as early as the 17th century, with a number settling in Mexico City, most of whom originated from Taishan, Guangdong, Qing China. Immigration increased when Mexican president Porfirio Díaz attempted to encourage foreign investment and tourism to boost the country's economy. The two countries signed a Treaty of Amity and Commerce in 1899; over time, the Cantonese expatriates began to establish profitable businesses such as wholesale and retail groceries. By 1910, there were 13,200 Chinese immigrants in the country, many living in Baja California, Chihuahua, Coahuila, Sinaloa, Sonora, and Yucatán.

Torreón was an attractive destination for immigrants at the turn of the nineteenth century. It was located at the intersection of two major railroads (the Mexican Central Railway and the Mexican International Railroad) and was proximate to the Nazas River, which irrigated the surrounding area, making it a suitable location for growing cotton. The Cantonese probably began to arrive in Torreón during the 1880s or 1890s, at the same time that other immigrants were first recorded as coming to the city. By about 1900, 500 of the city's 14,000 residents were Chinese. The Chinese community was easily the largest and most notable group of immigrants in the city. By 1903, it had formed the largest branch of the Baohuanghui (Protect the Emperor Society) in Mexico.

On October 17, 1903, President Porfirio Diaz set up a commission to look at the impact of Chinese immigration to Mexico. The final 121-page report—published in 1911, written by José María Romero—established that Chinese immigration, whether at an individual or group level, was not to the greater benefit of Mexico.

Mexico was one of the countries visited by Kang Youwei after his failed Hundred Days' Reform in Qing China. He had recently founded the China Reform Association to restore the Guangxu Emperor to power, and was visiting Chinatowns worldwide to fund the Association. He arrived in 1906, and purchased a few blocks of real estate in Torreón for 1,700 pesos, later reselling it to Cantonese immigrants for a profit of 3,400 pesos. This investment spurred Kang to have the Association establish a bank in Torreón, which began selling stock and real estate to Cantonese businessmen. The bank also built the city's first tram line. Kang visited Torreón again in 1907. It has been suggested that the city served as a test case for Cantonese immigration to Mexico and Brazil, which Kang believed might solve overpopulation problems in the Pearl River Delta, Guangdong. Soon there were 600 Chinese living in the city.

In 1907, a number of Mexican businessman gathered to form a chamber of commerce to protect their businesses from the foreigners. Instead of targeting Chinese specifically, they wrote:

We cannot compete against the foreigners in commercial ventures. The sad and lamentable fact is that the prostration of our national commerce has created a situation in which Mexicans are replaced by foreign individuals and companies, which monopolize our commerce and behave in the manner of conquerors in a conquered land.

Tensions and resentment of the Chinese ran high among the Mexican populace of Torreón, stemming from the immigrants' prosperity and monopoly over the grocery trade. Nationwide resentment of the Chinese has also, conversely, been attributed to the fact that the Chinese represented a source of cheap-labor which was central to the Porfirian economic program. Therefore, opposing the Chinese was an indirect way to oppose the dictatorship.

Anti-Chinese sentiments were apparent in the Independence Day speeches and demonstrations of 16 September 1910. Over the next several weeks a number of Chinese establishments were vandalized.

Events

Events leading to the massacre

On 5 May 1911 (Cinco de Mayo), a revolutionary leader, a bricklayer or stonemason named Jesús C. Flores, made a public speech in nearby Gómez Palacio, Durango, in which he claimed that the Chinese were putting Mexican women out of jobs, had monopolized the gardening and grocery businesses, were accumulating vast amounts of money to send back to China, and were "vying for the affection and companionship of local women." He concluded by demanding that all people of Chinese origin be expelled from Mexico. One witness recalled him stating "that, therefore, it was necessary... even a patriotic duty, to finish with them."

The branch of the reform association in Torreón heard of Flores' speech, and on 12 May the society's secretary, Woo Lam Po (also the manager of the bank) circulated a letter in Chinese among the leaders of the community warning that there could be violence:

Brothers, attention! Attention! This is serious. Many unjust acts have happened during the revolution. Notice have [sic] been received that before 10 o'clock today the revolutionists will unite their forces and attack the city. It is very probable that during the battle a mob will spring up and sack the stores. For this reason, we advise all our people, when the crowds assemble, to close your door and hide yourself and under no circumstances open your places for business or go outside to see the fighting. And if any of your stores are broken into, offer no resistance but allow them to take what they please, since otherwise you might endanger your lives. THIS IS IMPORTANT. After the trouble is over we will try to arrange a settlement.

Siege of Torreón

On the morning of Saturday, 13 May, the forces of the Mexican Revolution led by Francisco I. Madero's brother Emilio Madero attacked the city. Its railroads made it a key strategic point necessary to seizing complete control of the surrounding region: it was also the last major city to be targeted by the rebels. Madero and 4,500 Maderistas surrounded the city, hemming in General Emiliano Lojero and his 670 Federales. They overran the Chinese gardens surrounding the city, killing 112 of the people working there. Chinese houses were used as fortifications for the advancing rebels, and the people living there were forced to prepare them food. The fighting continued until the Federales began to run low on munitions on Sunday evening. Lojero ordered a retreat, and his forces abandoned the city under cover of darkness between two and four in the morning on Monday, 15 May, during a heavy rainstorm. The retreat was so sudden that some troops were left behind during the evacuation. Before the rebels entered the city, witnesses reported that xenophobic speeches had been made to incense the accompanying mob against foreigners. Jesús Flores was present, and made a speech calling the Chinese "dangerous competitors" and concluded "that it would be best to exterminate them."

Massacre

The rebel forces entered the city at six o'clock, accompanied by a mob of over 4,000 men, women, and children from Gómez Palacio Municipality, Viesca Municipality, San Pedro Municipality, Lerdo Municipality, and Matamoros Municipality. They were joined by citizens of Torreón and began the sacking of the business district. The mob released prisoners from jail, looted stores, and attacked people on the street. They soon moved to the Chinese district. Men on horses drove Chinese from the gardens back into town, dragging them by their queues and shooting or trampling those who fell. Men, women, and children were killed indiscriminately when they fell in the way of the mob, and their bodies were robbed. The mob finally reached the bank, where they killed the employees.

A number of residents made attempts to save the Chinese from the mob. Seventy immigrants were saved by a tailor who stood atop the roof of a building where they were hiding and misdirected the mob that was hunting for them. Eleven were saved by Hermina Almaráz, the daughter of a Maderista leader, who told soldiers who wanted to take them from her home "that they could only enter the house over her dead body." Another eight were saved by a second tailor, who stood in the rain in front of the laundry they worked at and lied to the rebels about their presence.

Ten hours after the massacre had begun, at around four o'clock, Emilio Madero arrived in Torreón on horseback and issued a proclamation decreeing the death penalty for anyone who killed a Chinese. This ended the massacre.

After the massacre

Madero collected the surviving Chinese in a building and posted a hand-picked group of soldiers to protect them. Dead Mexicans were buried in the city's cemetery, but the bodies of the slain Chinese were buried together in a trench.

The same day as the massacre, Madero convened a military tribunal to hear testimony about the killings. The tribunal came to the conclusion that the Maderistas had "committed atrocities", but the soldiers defended themselves by asserting that the Chinese had been armed and the massacre was an act of self-defense.

Both the United States Consulate and the local Relief Committee began collecting donations from locals to support the Chinese. Between 17 May and 1 June, Dr. J. Lim and the Relief Committee collected more than $6,000, which they distributed at a rate of $30 per day to provide food and shelter for the survivors.

Aftermath

Events following the massacre

After the massacre, large numbers of Chinese fled Torreón, with El Imparcial, a daily newspaper in Mexico City, reporting that over 1,000 people were on the move. Chinese began to arrive in Guadalajara seeking passage back to China.

Property stolen from Torreón continued to appear on the black market in San Pedro for several months following the massacre and looting.

Casualties

308 Asians were killed in the massacre; 303 Chinese and 5 Japanese. According to the British Vice Consul in Gómez Palacio, the Japanese were killed "owing to the similarity of features" with the Chinese. It is estimated that the dead made up nearly one-half of the Chinese population.

Among the dead were 50 employees of Sam Wah, both from his estate and his restaurant; Wong Foon Chuck lost 45 employees: 32 from his estate, nine from a railroad hotel that he operated, and four from his laundry; and Ma Due lost 38 out of the 40 workers from his gardens. 25 employees of the bank were also killed.

Rebels, Federales, and bystanders were also killed; according to contemporary reports, these included 25 Federales, 34 bystanders (including 12 Spaniards and a German), and 26 Maderistas. Among the dead was Jesús Flores, apparently killed while attempting to free a machine gun abandoned by the government forces.

Property damage

One estimate put the total damage at around US$1,000,000 (equivalent to $31,407,143 in 2022). Chinese properties were dealt US$849,928.69 ($26,693,832) in damage. Among the businesses destroyed were the bank, the Chinese Club, 40 groceries, five restaurants, four laundries, 10 vegetable stands and 23 other food stands. Almost 100 Chinese homes and businesses were destroyed in total. Also destroyed were a number of the Chinese-owned gardens outside of town. In addition to businesses and commercial establishments, an unknown number of residential buildings were robbed and destroyed. An American consular agent named G. C. Carothers described the destruction in a June 7 report on the massacre:

Next we went to the Chinese Laundry were four had been killed, and the laundry practically demolished. Bombs had been thrown on the roof, the windows and doors either destroyed or stolen, the machinery broken to pieces and everything that could be carted away, stolen.... The Puerto de Shanghai building was next visited. All of the doors and windows of the building were destroyed. The Chinese Bank, which had been moved into this building a few months before, was demolished, safes blown open and contents taken, furniture destroyed, all papers and valuables stolen.

American, Arabian, German, Spanish, and Turkish establishments were also damaged and destroyed, but in contrast to the Chinese, U.S. properties were only dealt US$22,000 ($690,957 today) in damage.

Other properties destroyed included a casino, the city courthouse, the jail, the police headquarters, the Inferior Court, the Court of Letters, and the Municipal Treasury.

Further unrest

The massacre in Torreón was not the only instance of race violence against the Chinese during the revolution. In the first year alone, rebels and other Mexican citizens contributed to the deaths of some 324 Chinese. By 1919, another 129 had been killed in Mexico City, and 373 in Piedras Negras. The persecution and violence against the Chinese in Mexico finally culminated in 1931, with the expulsion of the remaining Chinese from Sonora.

See also

In Spanish: Matanza de chinos de Torreón para niños

In Spanish: Matanza de chinos de Torreón para niños