Vita Sackville-West facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Vita Sackville-West

|

|

|---|---|

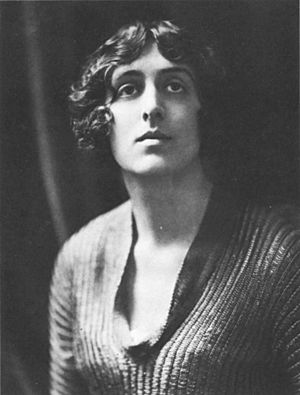

Sackville-West around 1915, from The Life of V.Sackville-West by Victoria Glendinning

|

|

| Born | Victoria Mary Sackville-West 9 March 1892 Knole House, Kent, England |

| Died | 2 June 1962 (aged 70) Sissinghurst Castle, Kent, England |

| Occupation | Novelist, poet, garden designer |

| Nationality | British |

| Period | 1917–1960 |

| Spouse | |

| Children |

|

| Parents |

|

Victoria Mary, Lady Nicolson, CH (née Sackville-West; 9 March 1892 – 2 June 1962), usually known as Vita Sackville-West, was an English author and garden designer.

Sackville-West was a successful novelist, poet and journalist, as well as a prolific letter writer and diarist. She published more than a dozen collections of poetry and 13 novels during her life. She was twice awarded the Hawthornden Prize for Imaginative Literature: in 1927 for her pastoral epic, The Land, and in 1933 for her Collected Poems. She was the inspiration for the protagonist of Orlando: A Biography, by her friend and lover Virginia Woolf.

She wrote a column in The Observer from 1946 to 1961 and is remembered for the celebrated garden at Sissinghurst in Kent, created with her husband, Sir Harold Nicolson.

Contents

Biography

Antecedents

Victoria Mary Sackville-West — called Vita, to distinguish her from her mother — was born on 9 March 1892 at Knole, the Kent home of Sackville-West's aristocratic ancestors. She was the only child of cousins Victoria Sackville-West and Lionel Sackville-West, 3rd Baron Sackville. Vita's mother, the illegitimate daughter of Lionel Sackville-West, 2nd Baron Sackville and the Spanish dancer Pepita (Josefa de Oliva, née Durán y Ortega), had been raised in a Parisian convent.

Although the marriage of Sackville-West's parents was initially happy, the couple drifted apart shortly after her birth, and Lionel took an opera singer who came to live with them at Knole as his mistress.

Knole had been given to Thomas Sackville by Elizabeth I, in the sixteenth century. The Sackville-West family followed the English aristocracy's inheritance customs, preventing Vita from inheriting Knole upon the death of her father; this was a source of life-long bitterness for her. The house followed the title, and was bequeathed instead by her father to his brother Charles, who became the 4th Baron.

Early life

Sackville-West was initially taught at home by governesses and later attended Helen Wolff's school for girls, an exclusive day school in Mayfair, where she met first loves Violet Keppel and Rosamund Grosvenor. She did not befriend local children and found it hard to make friends at school. Her biographers characterise her childhood as one filled by loneliness and isolation. She wrote prolifically at Knole, penning eight full-length (unpublished) novels between 1906 and 1910, ballads and many plays, some in French. Her lack of formal education led to later shyness with her peers, such as those in the Bloomsbury Group. She felt herself to be sluggish of mind and she was never at the intellectual heart of her social group.

Sackville-West's apparently Roma lineage introduced a passion for "gypsy" ways, a culture she perceived to be hot-blooded, heart-led, dark, and romantic. It was a strong theme in her writing. Sackville-West visited Roma camps and felt herself to be at one with them. During her childhood, Vita spent a great deal of time in Paris.

Marriage to Harold Nicholson

Sackville-West was courted for 18 months by young diplomat Harold Nicolson, whom she found to be a secretive character. Vita's parents were opposed to the marriage on the grounds that "penniless" Nicolson had an annual income of only £250. He was the third secretary at the British Embassy in Constantinople and his father had been made a peer only under Queen Victoria. Another of Sackville-West's suitors, Lord Granby, had an annual income of £100,000, owned vast acres of land and was heir to an old title, Duke of Rutland.

Following the pattern of his father's career, Harold Nicolson was at various times a diplomat, journalist, broadcaster, Member of Parliament, and author of biographies and novels. After the wedding the couple lived in Cihangir, a suburb of Constantinople (now Istanbul), the capital of the Ottoman Empire. Sackville-West loved Constantinople, but the duties of a diplomat's wife did not appeal to her. It was only during this time that she attempted to don, with good grace, the part of a "correct and adoring wife of the brilliant young diplomat", as she sarcastically wrote. When she became pregnant, in the summer of 1914, the couple returned to England to ensure that she could give birth in a British hospital.

The family lived at 182 Ebury Street, Belgravia and bought Long Barn in Kent as a country house (1915–1930). They employed the architect Edwin Lutyens to make improvements to the house. The British declaration of war on the Ottoman Empire in November 1914, following Ottoman naval attacks on Russia, precluded any return to Constantinople.

The couple had two children: Benedict (1914–1978), an art historian, and Nigel (1917–2004), a well-known editor, politician, and writer. Another son was stillborn in 1915.

Sissinghurst

In 1930 the family acquired and moved to Sissinghurst Castle, near Cranbrook, Kent. It had once been owned by Vita's ancestors. This gave it a dynastic attraction as she was excluded from inheriting Knole and a title. Sissinghurst was an Elizabethan ruin and the creation of the gardens would be a joint labour of love that would last many decades, first entailing years of clearing debris from the land. Nicolson provided the architectural structure, with strong classical lines, which would frame his wife's innovative informal planting schemes. She created a new and experimental system of enclosures or rooms, such as the White Garden, Rose Garden, Orchard, Cottage Garden and Nuttery. She also innovated single colour-themed gardens and design principles orientating the visitors' experience to discovery and exploration. Her first garden at Long Barn (Kent, 1915–1930) was experimental, a place of learning by trial and error and she carried over her ideas and projects to Sissinghurst, utilising her hard won experience. Sissinghurst was first opened to the public in 1938.

Sackville-West took up writing again in 1930 after a six-year break as she needed money to pay for Sissinghurst. Nicolson, having left the Foreign Office, no longer had a diplomat's salary to draw upon. She also had to pay tuition for her two sons to attend Eton College. She felt she had become a better writer thanks to the mentorship of Woolf. In 1947 she began a weekly column in The Observer called "In your Garden", although she was not a trained horticulturalist or designer. She continued the very popular column until a year before her death, and writing helped to make Sissinghurst one of the most famous and visited gardens in England. In 1948 she became a founder member of the National Trust's garden committee. The grounds are now run by the National Trust. She was awarded the Veitch Memorial Medal from the Royal Horticultural Society.

Writing

In the early 1920s Sackville-West wrote a memoir of her relationships. The work, titled Portrait of a Marriage, was not published until 1973. The memoir was dramatised by the BBC (and PBS in North America) in 1990, starring Janet McTeer as Vita, and Cathryn Harrison as Violet. The series won four BAFTAs.

Most of Sackville-West's novels were an immediate success (except Dark Island, Grand Canyon and La Grande Mademoiselle). The Edwardians (1930) and All Passion Spent are perhaps her best-known novels today. The latter was dramatised by the BBC in 1986 starring Dame Wendy Hiller.

A recently rediscovered work from 1922 "A Note of Explanation" was written specifically to be a part of the miniature collection of books within the doll's House, and tells the story of a sprite that inhabits the doll's house and re-tells several fairy tales from the point of view of the sprite, indicating how they had influenced the story. The book was adapted for the stage by Emily Ingram under the title "A Sprite in the Doll's House" in 2019 and was performed in Edinburgh, at the Palace of Holyrood House as part of their Christmas festivities.

The poetry remains the least known of Sackville-West's work. It encompassed epics and translations of volumes such as Rilke's Duino Elegies. Her epic poems The Land (1926) and The Garden (1946) reflect an enduring passion for the earth and family tradition.The Land may have been written in response to the central work of Modernist poetry The Waste Land (also published by Hogarth Press). She dedicated her poem to Dorothy Wellesley. The poem won the Hawthornden Prize in 1927. She won it again in 1933 with her Collected Poems, becoming the only writer to do so twice. The Garden won the Heinemann Award for literature.

She is not well known as a biographer. The most famous of those works is her biography of Saint Joan of Arc in the work of the same name. Additionally, she composed a dual biography of Saint Teresa of Ávila and Thérèse of Lisieux entitled The Eagle and the Dove, a biography of the author Aphra Behn, and a biography of her maternal grandmother, the Spanish dancer known as Pepita.

Despite being a shy woman, Sackville-West often forced herself to participate in literary readings before book clubs and on the BBC in order to feel a sense of belonging. Her love of the classical traditions in literature put her out of favour with modernist critics and by the 1940s, she was often dismissed as a dated writer, much to her chagrin. In 1947 Sackville-West was made a Fellow of the Royal Society of Literature and Companion of Honour.

Death and legacy

Vita Sackville-West died at Sissinghurst in June 1962, aged 70, from abdominal cancer. She was cremated and ashes buried in the family crypt within the church at Withyham, eastern Sussex.

Sissinghurst Castle is owned by the National Trust. Her son Nigel Nicolson lived there after her death, and following his death in 2004 his own son Adam Nicolson, Baron Carnock, came to live there with his family. With his wife, the horticulturalist Sarah Raven, they committed to restore the mixed working farm and growing food on the property for residents and visitors, a function that had withered under the aegis of the Trust.

The film Vita and Virginia, with Gemma Arterton as Vita and Elizabeth Debicki as Virginia, had its world premiere at the 2018 Toronto International Film Festival. It is directed by Chanya Button and based on a play by Eileen Atkins, created from the love letters between Sackville-West and Woolf. The play was first performed in London in October 1993 and off Broadway in November 1994.

Works

Fiction

Poetry

In her poetry, she often engaged themes of natural life and romantic love. She published more than a dozen collections of poetry during her life, listed here:

- Timgad: [a poem] (1900)

- Constantinople: eight poems (1915)

- Poems of West & East (1917) (also credited as Mrs. Harold Nicolson)

- The Land (1926)

- King's daughter (1929)

- Invitation to cast out care (1931)

- Sissinghurst (1931)

- Collected poems (1933)

- Solitude: a poem (1938)

- The Garden (1946)

- Lost poem (or A Madder Caress) (2013)

Novels

- Heritage (1919)

- The dragon in shallow waters (1920)

- Challenge (1920)

- Grey Wethers: a romantic novel (1923)

- The Edwardians (1930)

- All Passion Spent (1931)

- Family History (1932)

- The Dark Island (1934)

- Grand Canyon: A Novel (1942)

- Devil at Westease: the story as related by Roger Liddiard (1947)

- The Easter party (1953)

- No Signposts in the Sea (1961)

Children's books

- A Note of Explanation (written for Queen Mary's Dolls' House in 1924, published posthumously in 2017)

Short stories

- Orchard and vineyard (1892)

- The heir: a love story (1922)

- Thirty Clocks Strike the Hour, and other stories (1932)

- The death of Noble Godavary (Gottfried Künstler, 1932)

- Another world than this ..: an anthology (1945)

- Nursery rhymes (1947)

Plays

- Chatterton: a drama in three acts (1909)

Non-fiction

Letters

- Dearest Andrew: letters from V. Sackville-West to Andrew Reiber, 1951-1962 (1979)

- The Letters of Vita Sackville-West to Virginia Woolf (edited by Louise A. DeSalvo and Mitchell A. Leaska, Arrow, 1984)

- Vita and Harold: The Letters of Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson (1992)

- Violet to Vita: The Letters of Violet Trefusis to Vita Sackville-West 1910–1921 (edited by Mitchell A. Leaska and John Phillips, 1991)

- Portrait of a Marriage: Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson by Nigel Nicolson, Vita Sackville-West (compiled by her son Nigel Nicolson from her journals and letters, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1973)

- Love Letters: Vita and Virginia by Virginia Woolf and Vita Sackville-West (introduction by Alison Bechdel Vintage Classics, 2021)

Biographies

- Aphra Behn, the incomparable Astrea (Gerald Howe, 1927)

- Andrew Marvell (1929)

- Saint Joan of Arc (Doubleday 1936, reprinted M. Joseph 1969)

- Pepita (Doubleday, 1937, reprinted Hogarth Press 1970)

- The eagle and the dove, a Study in Contrasts: St. Teresa of Avila and St. Thérèse of Lisieux (M. Joseph, 1943)

- Daughter of France: the life of Anne Marie Louise d'Orléans, duchesse de Montpensier, 1627-1693, La Grande Mademoiselle (1959)

Guides

- Knole and the Sackvilles (1922) - a history of her ancestral home

- Passenger to Teheran (Hogarth Press 1926, reprinted Tauris Parke Paperbacks 2007, ISBN: 978-1-84511-343-8)

- Twelve Days: an account of a journey across the Bakhtiari Mountains of South-western Persia (first published UK 1927; Doubleday Doran 1928; M. Haag 1987, reprinted Tauris Parke Paperbacks 2009 as Twelve Days in Persia)

- How does your garden grow? (1935) (Beverley Nichols, Compton Mackenzie, Marion Dudley Cran, Vita Sackville-West)

- Some flowers (1937)

- Country notes (1939)

- Country Notes in Wartime (Hogarth Press, 1940)

- English country houses (William Collins, 1941, illustrated)

- The Women's Land Army (M. Joseph / Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries, 1944)

- Exhibition Catalogue: Elizabethan portraits (1947)

- Knole, Kent (1948)

- In Your Garden (1951)

- In your garden again (1953)

- Walter de la Mare and The traveller (1953)

- More for your garden (1955)

- Even more for your garden (1958)

- Joy of Gardening: a selection for Americans (1958)

- Berkeley Castle (1960)

- Faces: profiles of dogs (Harvill Press, 1961, photographs by Laelia Goehr)

- Garden Book (1975)

- Hidcote Manor Garden, Gloucestershire (1976)

- Une Anglaise en Orient (1993)

Translations

- Duineser Elegien: Elegies from the Castle of Duino, translated from the German of Rainer Maria Rilke by V. and Edward Sackville-West (1931)

In 1931, Virginia and Leonard Woolf’s Hogarth Press published in London a small run of a beautiful edition of Rainer Maria Rilke’s Duino Elegies. This marked the English debut of Rilke’s masterpiece, which would eventually be rendered in English over 20 times, influencing countless poets, musicians and artists across the English-speaking world.

Influences

- Orlando: A Biography by Virginia Woolf (Hogarth Press, 1928)

- Behind the Mask: The Life of Vita Sackville-West by Matthew Dennison (2014)

See also

In Spanish: Vita Sackville-West para niños

In Spanish: Vita Sackville-West para niños

- List of Bloomsbury Group people