Yu Gwansun facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

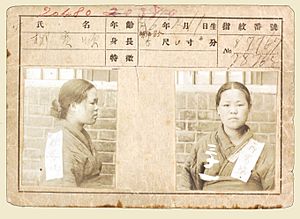

Yu Gwan-sun

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | December 16, 1902 Cheonan, South Chungcheong, Korea

|

| Died | September 28, 1920 (aged 17) |

| Known for | March 1st Movement |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives |

|

| Korean name | |

| Hangul | 류관순 |

| Hanja | 柳寬順 |

| Revised Romanization | Ryu Gwan-sun |

| McCune–Reischauer | Ryu Kwan-sun |

Yu Gwan-sun (Hangul: 유관순, Hanja: 柳寬順) (December 16, 1902 – September 28, 1920) was a Korean independence activist organizer in what would come to be known as the March First Independence Movement against Imperial Japanese colonial rule of Korea in South Chungcheong. The movement was a peaceful demonstration by the Korean people against Japanese rule. Yu became one of the most famous figures in this movement and later a symbol of Korea's fight for independence.

Contents

Early life and education

Yu Gwan-sun was born into the Goheung Ryu clan on December 16, 1902, near Cheonan, in South Chungcheong Province of Korea as the second child of three children. Her family was influenced by her grandfather Ryu Yoon-gi and her uncle Ryu Joong-moo, who were Protestants, and she also grew up in this atmosphere. She was considered an intelligent child and could memorize Bible passages after hearing them only once. She attended the school Ewha Hakdang, today known as Ewha Womans University, through a scholarship program that required recipients to work as a teacher after graduation. At the time, few women in the country attended university. In 1919 while a student at the Ewha Girls' High School, she witnessed the beginnings of the March First Independence Movement. Yu, along with a five-person group, took part in the movement and attended demonstrations in Seoul. On March 10, 1919, all of the schools, including the Ewha Women's School, were temporarily closed by the Governor-General of Korea, and Yu returned home to Cheonan.

Political activism

On March 1, 1919, Seoul was overflowing with marches by people nationwide protesting Japanese occupation of Korea. After this protest, organizers arrived at Ewha Haktang and encouraged Yu and her friends to join a demonstration that would take place in three days on March 5, 1919. Together with her classmates, Yu marched to Namdaemun in Central Seoul. There, they were detained by the police, but were shortly freed after missionaries from their school negotiated for their release. Yu left Seoul after the Japanese government ordered all Korean schools to close on March 10 in response to the protests. She returned to her village of Jiryeong-ri (now Yongdu-ri) and there, she took a more active role in the movement.

Aunae Market demonstration and arrest

Along with her family, Yu went door to door and encouraged the public to join the independence movement, which was starting to take shape. She spread the word of an organized demonstration that she planned with Cho In-won and Kim Goo-Eung and rallied the people from neighboring towns, including Yeongi, Chungju, Cheonan and Jincheon. The demonstration took place on April 1, 1919 (March 1 in the lunar calendar), at Aunae Marketplace at 9a.m., with approximately 3,000 demonstrators chanting "Long live Korean independence!" (Korean: "대한독립만세"). By 1 p.m., Japanese military police arrived and fired on the unarmed protesters, killing 19 people, including Yu's parents. She was arrested.

The Japanese military police offered Yu a lighter sentence in exchange for admission of guilt and her cooperation in finding other protest collaborators. She refused, and remained silent even after being severely tortured.

Imprisonment and utterance

After her arrest, Yu was initially detained at Cheonan Japanese Military Police Station and later transferred to Gongju Police Station. At her trial, she argued that the proceedings were controlled by the Japanese colonial government, the law of the governor-general of Korea, and was overseen by an assigned Japanese judge. Despite her attempts to obtain a fair trial, she was found guilty of sedition and security law violations and received a five-year sentence at Seodaemun Prison in Seoul. During her imprisonment, Yu's continued support for the independence movement resulted in her being severely punished and tortured in prison.

On March 1, 1920, Yu prepared a large-scale protest with her fellow inmates to mark the movement's first anniversary. Yu was imprisoned separately in an isolated cell. She died on September 28, 1920, from injuries sustained from torture and beatings in prison. According to records discovered in November 2011, 7,500 of the 45,000 arrested in relation to the protests during that period died at the hands of Japanese authorities.

"Japan will fall", she wrote while in prison:

Even if my fingernails are torn out, my nose and ears are ripped apart, and my legs and arms are crushed, this physical pain does not compare to the pain of losing my nation. [...] My only remorse is not being able to do more than dedicating my life to my country.

After death

Japanese prison officials initially refused to release Yu's body in an attempt to hide evidence of torture. Authorities eventually released her body in a Saucony Vacuum Company oil crate due to threats made by Lulu Frey and Jeannette Walter, the principals of Yu's school, who voiced their suspicions of torture to the public. Walter, who dressed Yu for her funeral, later assured the public in 1959 that her body had not been cut into pieces as alleged. On October 14, 1920, Yu's funeral was held at Jung-dong Church by Reverend Kim Jong-wu and her body was buried in a public cemetery in Seoul's Itaewon district. The cemetery was later destroyed.

After national liberation in 1945, a shrine was built in the township of Byeongcheon-myeon with the cooperation of Chungcheongnam-do Province and the Cheonan army. Since 1946, a memorial service organized by people from Ewha Womans University has honored Yu. Around this time, people who took Yu's coffin from Seodaemun Prison opened the box, and this triggered rumors that the body had been cut into pieces.

Her body was buried in Itaewon Cemetery, but the body disappeared while the Japanese Empire was moving the tomb to make it a military base. Currently, her grave in Cheonan, Chungcheongnam-do, has no body.

Legacy

Yu became known as "Korea's Joan of Arc". While the March 1 movement did not immediately gain freedom for Korea, the Japanese colonial government soon implemented more lenient political controls. Because she never abandoned her convictions even after her arrest, Yu became a symbol of the Korean independence movement through her unrelenting protests and resistance. After Korea gained independence, a shrine was built in honor of Yu with the cooperation of South Chungcheong province and the city of Cheonan.

She was posthumously awarded the Order of Independence Merit in 1962.

In 2018 The New York Times published a belated obituary.

Declaration of independence by the women of Korea

"Today, when the world claims peace (...), we must live under the rule of law, but we must live without fear and fear for our own children. It is our duty to become an active new nation under the rule of independence and to follow these teachers in the basement of Gucheon without any difficulties. With tears rising from the soy sauce and hard work coming from the music, we will lie down on our beloved fellow Koreans! Do not let the time be too early to do anything; let the work run fast."

Award of Yu Gwan-sun

In South Chungcheong Province, a group of women (include students) or group that have contributed to the development of the nation and the community are selected from all over the country, honoring the patriot Yu Gwan-sun.

Name spelling

Yu Gwan-sun was born into the Goheung Ryu clan.

In the South Korean standard of the Korean language, the initial ㄹ at the start of words is dropped when spoken, and is called the "initial sound rule" (두음법칙). In Yu Gwan-sun's case, the pronunciation of the family name 柳 becomes 유 even if its canonical ("dictionary") pronunciation is 류. This convention is also understood in written Korean, and native readers will recognise both written 유 and 류 as references to the same underlying hanja character. The two hangul spellings of 유 and 류 correspond to Yu and Ryu respectively in the revised romanisation. However, this "initial sound rule" was subject to the debate. As the new regulation was introduced in 1994 to also include hangul spelling in addition to hanja characters for the names in the family register, the Supreme Court of Korea ruled in 1995 that the hanja 柳 was to be recorded as 유 (and not 류) in hangul. In April 2007, however, the application was made to a local court to allow the surname change from 유 to 류 spelling in the family register if individual wished, and various state agencies discussed the spelling issue. As a result, along with the hangul spelling 유, the spelling 류 also has been allowed to be used in the family register, which was confirmed by the South Korean Constitutional Court.

While the Yu-Gwansun Memorial Association (Hangul: 유관순열사사기념사업회), a non-profit organization registered with the Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs (Hangul: 국가보훈처), used 유 from its founding in 1947 and changed it to 류 in 2001, it reverted to the 유 spelling in 2014, citing a need to remove confusion, in light of the consistent use of 유 by textbooks and both official Korean government and unofficial texts.

Popular culture

Film

- Portrayed by Go Chun-hee in the 1948 film Yu Gwan-sun

- Portrayed by Do Geum-bong in the 1959 film Yu Gwan-sun

- Portrayed by Eom Aeng-ran in the 1966 film Yu Gwan-sun

- Portrayed by Moon Ji-hyun in the 1974 film Yu Gwan-sun

- Portrayed by Go Ah-seong in the 2019 film A Resistance

- Portrayed by Lee Sae-bom in the 2019 film 1919 Yu Gwan-sun

Animation

- Portrayed by Jung Mi-sook in the 1993-1994 KBS animation series Cho-ryong's Old Travel

Art and Poetry

- Figures in the book Dictee by Theresa Hak Kyung Cha

See also

In Spanish: Ryu Gwansun para niños

In Spanish: Ryu Gwansun para niños