16th Street Baptist Church bombing facts for kids

Quick facts for kids 16th Street Baptist Church bombing |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Civil Rights movement and the Birmingham campaign | |

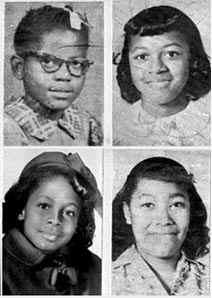

The four girls killed in the bombing (clockwise from top left) Addie Mae Collins (14), Cynthia Wesley (14), Carole Robertson (14), and Carol Denise McNair (11)

|

|

| Location | Birmingham, Alabama |

| Coordinates | 33°31′0″N 86°48′54″W / 33.51667°N 86.81500°W |

| Date | September 15, 1963; 60 years ago 10:22 a.m. (UTC-5) |

| Target | 16th Street Baptist Church |

|

Attack type

|

Bombing Domestic terrorism Right-wing terrorism |

| Deaths | 4 |

|

Non-fatal injuries

|

14–22 |

| Victims | Addie Mae Collins Cynthia Wesley Carole Robertson Carol Denise McNair |

| Perpetrators | Thomas Blanton (convicted) Robert Chambliss (convicted) Bobby Cherry (convicted) Herman Cash (alleged) |

| Motive | Racism and support for racial segregation |

The 16th Street Baptist Church bombing was a terrorist bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama, on Sunday, September 15, 1963. Four members of a local Ku Klux Klan chapter planted 19 sticks of dynamite attached to a timing device beneath the steps located on the east side of the church.

Described by Martin Luther King Jr. as "one of the most vicious and tragic crimes ever perpetrated against humanity," the explosion at the church killed four girls and injured between 14 and 22 other people.

Although the FBI had concluded in 1965 that the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing had been committed by four known Klansmen and segregationists: Thomas Edwin Blanton Jr., Herman Frank Cash, Robert Edward Chambliss, and Bobby Frank Cherry, no prosecutions were conducted until 1977.

As part of a revival effort by states and the federal government to prosecute cold cases from the civil rights era, the state conducted trials in the early 21st century of Thomas Edwin Blanton Jr. and Bobby Cherry, who were each sentenced to life imprisonment in 2001 and 2002, respectively. Future United States Senator Doug Jones successfully prosecuted Blanton and Cherry. Herman Cash had died in 1994, and was never charged with his alleged involvement in the bombing.

The 16th Street Baptist Church bombing marked a turning point in the United States during the civil rights movement and also contributed to support for the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 by Congress.

Contents

Background

In the years leading up to the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, Birmingham had earned a national reputation as a tense, violent and racially segregated city, in which even tentative racial integration in any form was met with violent resistance. Martin Luther King Jr. described Birmingham as "probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States." Birmingham's Commissioner of Public Safety, Theophilus Eugene "Bull" Connor, led the effort in enforcing racial segregation in the city through the use of violent tactics.

Black and white residents of Birmingham had access to different public amenities such as water fountains and places of public gathering such as movie theaters. The city had no black police officers or firefighters and most black residents could expect to find menial employment in professions such as cooks and cleaners. Black residents did not just experience segregation in the context of leisure and employment, but also in the context of their freedom and well-being. Given the state's disenfranchisement of most black people since the turn of the century, by making voter registration essentially impossible, few of the city's black residents were registered to vote. Bombings at black homes and institutions were a regular occurrence, with at least 21 separate explosions recorded at black properties and churches in the eight years before 1963. However, none of these explosions had resulted in fatalities. These attacks earned the city the nickname "Bombingham".

Birmingham Campaign

Civil Rights activists and leaders in Birmingham fought against the city's deeply-ingrained and institutionalized racism with tactics that included the targeting of Birmingham's economic and social disparities. Their demands included that public amenities such as lunch counters and parks be desegregated, the criminal charges against demonstrators and protestors should be removed, and an end to overt discrimination with regards to employment opportunities. The intentional scope of these activities was to see the end of segregation across Birmingham and the South as a whole. The work these Civil Rights activists were engaged in within Birmingham was crucial to the movement as the Birmingham campaign was seen as guidance for other cities in the South with regards to rising against segregation and racism.

The three-story 16th Street Baptist Church was a rallying point for civil rights activities through the spring of 1963. When the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) and the Congress on Racial Equality became involved in a campaign to register African Americans to vote in Birmingham, tensions in the city increased. The church was used as a meeting-place for civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph David Abernathy, and Fred Shuttlesworth, for organizing and educating marchers. It was the location where students were organized and trained by the SCLC Director of Direct Action, James Bevel, to participate in the 1963 Birmingham campaign's Children's Crusade after other marches had taken place.

On Thursday, May 2, more than 1,000 students, some reportedly as young as eight, opted to leave school and gather at the 16th Street Baptist Church. Demonstrators present were given instructions to march to downtown Birmingham and discuss with the mayor their concerns about racial segregation in the city, and to integrate buildings and businesses currently segregated. Although this march was met with fierce resistance and criticism, and 600 arrests were made on the first day alone, the Birmingham campaign and its Children's Crusade continued until May 5. The intention was to fill the jail with protesters. These demonstrations led to an agreement, on May 8, between the city's business leaders and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, to integrate public facilities, including schools, in the city within 90 days. (The first three schools in Birmingham to be integrated would do so on September 4.)

These demonstrations and the concessions from city leaders to the majority of demonstrators' demands were met with fierce resistance by other whites in Birmingham. In the weeks following the September 4 integration of public schools, three additional bombs were detonated in Birmingham. Other acts of violence followed the settlement, and several staunch Klansmen were known to have expressed frustration at what they saw as a lack of effective resistance to integration.

As a known and popular rallying point for civil rights activists, the 16th Street Baptist Church was an obvious target.

Bombing

In the early morning of Sunday, September 15, 1963, four members of the United Klans of America—Thomas Edwin Blanton Jr., Robert Edward Chambliss, Bobby Frank Cherry, and (allegedly) Herman Frank Cash—planted a minimum of 15 sticks of dynamite with a time delay under the steps of the church, close to the basement. At approximately 10:22 a.m., an anonymous man phoned the 16th Street Baptist Church. The call was answered by the acting Sunday School secretary, a 14-year-old girl named Carolyn Maull. The anonymous caller simply said the words, "Three minutes" to Maull before terminating the call. Less than one minute later, the bomb exploded. Five children were in the basement at the time of the explosion, in a restroom close to the stairwell, changing into choir robes in preparation for a sermon entitled "A Rock That Will Not Roll".

The explosion blew a hole measuring seven feet (2.1 m) in diameter in the church's rear wall, and a crater five feet (1.5 m) wide and two feet (0.61 m) deep in the ladies' basement lounge, destroying the rear steps to the church. Several cars parked near the site of the blast were destroyed, and windows of properties located more than two blocks from the church were also damaged. All but one of the church's stained-glass windows were destroyed in the explosion. The sole stained-glass window largely undamaged in the explosion depicted Christ leading a group of young children.

Hundreds of individuals, some of them lightly wounded, converged on the church to search the debris for survivors as police erected barricades around the church and several outraged men scuffled with police. An estimated 2,000 black people converged on the scene in the hours following the explosion. The church's pastor, the Reverend John Cross Jr., attempted to placate the crowd by loudly reciting the 23rd Psalm through a bullhorn.

Four girls—Addie Mae Collins (age 14, born April 18, 1949), Carol Denise McNair (age 11, born November 17, 1951), Carole Rosamond Robertson (age 14, born April 24, 1949), and Cynthia Dionne Wesley (age 14, born April 30, 1949)—were killed in the attack.

Between 14 and 22 additional people were injured in the explosion.

Reactions

Unrest and tensions

Violence escalated in Birmingham in the hours following the bombing, with reports of groups of black and white youth throwing bricks and shouting insults at each other. Police urged parents of black and white youths to keep their children indoors, as the Governor of Alabama, George Wallace, ordered an additional 300 state police to assist in quelling unrest. The Birmingham City Council convened an emergency meeting to propose safety measures for the city, although proposals for a curfew were rejected. Within 24 hours of the bombing, a minimum of five businesses and properties had been firebombed and numerous cars—most of which were driven by whites—had been stoned by rioting youths.

In response to the church bombing, described by the Mayor of Birmingham, Albert Boutwell, as "just sickening", the Attorney General dispatched 25 FBI agents, including explosives experts, to Birmingham to conduct a thorough forensic investigation.

As news of the church bombing and the fact that four young girls had been killed in the explosion reached the national and international press, many felt that they had not taken the civil rights struggle seriously enough. The day following the bombing, a young white lawyer named Charles Morgan Jr. addressed a meeting of businessmen, condemning the acquiescence of white people in Birmingham toward the oppression of blacks. In this speech, Morgan lamented: "Who did it [the bombing]? We all did it! The 'who' is every little individual who [...] spreads the seeds of his hate to his neighbor and his son ... What's it like living in Birmingham? No one ever really has known and no one will until this city becomes part of the United States." A Milwaukee Sentinel editorial opined, "For the rest of the nation, the Birmingham church bombing should serve to goad the conscience. The deaths ... in a sense, are on the hands of each of us."

Two more black youths were killed in Birmingham within seven hours of the Sunday morning bombing.

Some civil rights activists blamed George Wallace, Governor of Alabama and an outspoken segregationist, for creating the climate that had led to the killings. One week before the bombing, Wallace granted an interview with The New York Times, in which he said he believed Alabama needed a "few first-class funerals" to stop racial integration.

The city of Birmingham initially offered a $52,000 reward for the arrest of the bombers. Governor Wallace offered an additional $5,000 on behalf of the state of Alabama. Although this donation was accepted,

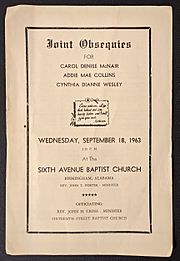

Funerals

Carole Rosamond Robertson was laid to rest in a private family funeral held on September 17, 1963.

The service for Carole Rosamond Robertson was held at St. John's African Methodist Episcopal Church. In attendance were 1,600 people. At this service, the Reverend C. E. Thomas told the congregation: "The greatest tribute you can pay to Carole is to be calm, be lovely, be kind, be innocent." Carole Robertson was buried in a blue casket at Shadow Lawn Cemetery.

On September 18, the funeral of the three other girls was held at the Sixth Avenue Baptist Church. Although no city officials attended this service, an estimated 800 clergymen of all races were among the attendees. Also present was Martin Luther King Jr. In a speech conducted before the burials of the girls, King addressed an estimated 3,300 mourners—including numerous white people—with a speech saying:

This tragic day may cause the white side to come to terms with its conscience. In spite of the darkness of this hour, we must not become bitter ... We must not lose faith in our white brothers. Life is hard. At times as hard as crucible steel, but, today, you do not walk alone.

As the girls' coffins were taken to their graves, King directed that those present remain solemn and forbade any singing, shouting or demonstrations. These instructions were relayed to the crowd present by a single youth with a bullhorn.

Initial investigation

Initially, investigators theorized that a bomb thrown from a passing car had caused the explosion at the 16th Street Baptist church. But by September 20, the FBI was able to confirm that the explosion had been caused by a device that was purposely planted beneath the steps to the church, close to the women's lounge. A section of wire and remnants of red plastic were discovered there, which could have been part of a timing device. (The plastic remnants were later lost by investigators.)

The FBI encountered difficulties in their investigation into the bombing. A later report stated: "By 1965, we had [four] serious suspects—namely Thomas Blanton Jr., Herman Frank Cash, Robert Chambliss, and Bobby Frank Cherry, all Klan members—but witnesses were reluctant to talk and physical evidence was lacking. Also, at that time, information from our surveillance was not admissible in court. As a result, no federal charges were filed in the '60s."

On May 13, 1965, local investigators and the FBI formally named Blanton, Cash, Chambliss, and Cherry as the perpetrators of the bombing, with Robert Chambliss the likely ringleader of the four. This information was relayed to the Director of the FBI, J. Edgar Hoover; however, no prosecutions of the four suspects ensued. There had been a history of mistrust between local and federal investigators. Later the same year, J. Edgar Hoover formally blocked any impending federal prosecutions against the suspects, and refused to disclose any evidence his agents had obtained with state or federal prosecutors.

In 1968, the FBI formally closed their investigation into the bombing without filing charges against any of their named suspects. The files were sealed by order of J. Edgar Hoover.

Resulting legislation

The Birmingham campaign, the March on Washington in August, the September bombing of the 16th Street Baptist church, and the November assassination of John F. Kennedy—an ardent supporter of the civil rights cause who had proposed a Civil Rights Act of 1963 on national television—increased worldwide awareness of and sympathy toward the civil rights cause in the United States.

Following the assassination of John F. Kennedy on November 22, 1963, newly-inaugurated President Lyndon Johnson continued to press for passage of the civil rights bill sought by his predecessor.

On July 2, 1964, President Lyndon Johnson signed into effect the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In attendance were major leaders of the Civil Rights Movement, including Martin Luther King Jr. This legislation prohibited discrimination based on race, color, religion, gender, or national origin; to ensure full, equal rights of African Americans before the law.

Formal reopening of the investigation

Officially, the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing remained unsolved until after William Baxley was elected Attorney General of Alabama in January 1971. Baxley had been a student at the University of Alabama when he heard about the bombing in 1963, and later recollected: "I wanted to do something, but I didn't know what."

Within one week of being sworn into office, Baxley had researched original police files into the bombing, discovering that the original police documents were "mostly worthless". Baxley formally reopened the case in 1971. He was able to build trust with key witnesses, some of whom had been reluctant to testify in the first investigation. Other witnesses obtained identified Chambliss as the individual who had placed the bomb beneath the church. Baxley also gathered evidence proving Chambliss had purchased dynamite from a store in Jefferson County less than two weeks before the bomb was planted, upon the pretext the dynamite was to be used to clear land the KKK had purchased near Highway 101. This testimony of witnesses and evidence was used to formally construct a case against Robert Chambliss.

After Baxley requested access to the original FBI files on the case, he learned that evidence accumulated by the FBI against the named suspects between 1963 and 1965 had not been revealed to the local prosecutors in Birmingham. Although he met with initial resistance from the FBI, in 1976 Baxley was formally presented with some of the evidence which had been compiled by the FBI, after he publicly threatened to expose the Department of Justice for withholding evidence which could result in the prosecution of the perpetrators of the bombing.

Prosecution of Robert Chambliss

On November 14, 1977, Robert Chambliss, then aged 73, stood trial in Birmingham's Jefferson County Courthouse. Chambliss had been indicted by a grand jury on September 24, 1977, charged with four counts of murder. But at a pre-trial hearing on October 18, Judge Wallace Gibson ruled that the defendant would be tried upon one count of murder—that of Carol Denise McNair—and that the remaining three counts of murder would remain, but that he would not be charged in relation to these three deaths.

Chambliss pleaded not guilty to the charges, insisting that although he had purchased a case of dynamite less than two weeks before the bombing, he had given the dynamite to a Klansman and FBI agent provocateur named Gary Thomas Rowe Jr.

On November 18, 1977, Robert Chambliss was found guilty of the murder of Carol Denise McNair. He was sentenced to life imprisonment.

Chambliss appealed his conviction, as provided under the law, saying that much of the evidence presented at his trial—including testimony relating to his activities within the KKK—was circumstantial; that the 14-year delay between the crime and his trial violated his constitutional right to a speedy trial; and the prosecution had deliberately used the delay to try to gain an advantage over Chambliss's defense attorneys. This appeal was dismissed on May 22, 1979.

Robert Chambliss died in the Lloyd Noland Hospital and Health Center on October 29, 1985, at the age of 81. In the years since his incarceration, Chambliss had been confined to a solitary cell to protect him from attacks by fellow inmates. He had repeatedly proclaimed his innocence, insisting Gary Thomas Rowe Jr. was the actual perpetrator.

Later prosecutions

In 1995, ten years after Chambliss died, the FBI reopened their investigation into the church bombing. It was part of a coordinated effort between local, state and federal governments to review cold cases of the civil rights era in the hopes of prosecuting perpetrators. They unsealed 9,000 pieces of evidence previously gathered by the FBI in the 1960s (many of these documents relating to the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing had not been made available to DA William Baxley in the 1970s). In May 2000, the FBI publicly announced their findings that the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing had been committed by four members of the KKK splinter group known as the Cahaba Boys. The four individuals named in the FBI report were Blanton, Cash, Chambliss, and Cherry. By the time of the announcement, Herman Cash had also died; however, Thomas Blanton and Bobby Cherry were still alive. Both were arrested.

On May 16, 2000, a grand jury in Alabama indicted Thomas Edwin Blanton and Bobby Frank Cherry on eight counts each in relation to the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing. Both named individuals were charged with four counts of first-degree murder, and four counts of universal malice. The following day, both men surrendered to police.

Blanton was sentenced to life imprisonment. He was incarcerated at the St. Clair Correctional Facility in Springville, Alabama. He died in prison from unspecified causes on June 26, 2020.

Bobby Frank Cherry was convicted of four counts of first-degree murder and sentenced to life imprisonment. He died of cancer on November 18, 2004, at age 74, while incarcerated at the Kilby Correctional Facility.

Aftermath

| They forever changed the face of this state and the history of this state. Their deaths made all of us focus upon the ugliness of those who would punish people because of the color of their skin. |

| —State Senator Roger Bedford at the unveiling of a state historic marker to the victims. September 15, 1990 |

- Following the bombing, the 16th Street Baptist Church remained closed for over eight months, as assessments and, later, repairs were conducted upon the property. Both the church and the bereaved families received an estimated $23,000 in cash donations from members of the public. Gifts totalling over $186,000 were donated from around the world. The church reopened to members of the public on June 7, 1964, and continues to remain an active place of worship today, with an average weekly attendance of nearly 2,000 worshippers. The current pastor of the church is the Reverend Arthur Price Jr.

- The most seriously injured survivor of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, Sarah Jean Collins, remained hospitalized for more than two months following the bombing. Collins' injuries were so extensive that medical personnel did initially fear she would lose the sight in both eyes, although, by October, they were able to inform Collins she would regain the sight in her left eye. When asked her feelings towards the bombers on October 15, 1963, Collins first thanked those who had cared for her and sent messages of condolence, flowers and toys, then said: "As for the bomber, people are praying for him. We wonder what he would be thinking today if he had children ... He will face God. We turn this problem over to God because no one else can solve Birmingham's problems. We leave it up to God to solve them."

- Charles Morgan Jr., the young white lawyer who had delivered an impassioned speech on September 16, 1963, deploring the tolerance and complacency of much of the white population of Birmingham towards the suppression and intimidation of blacks—thereby contributing to the climate of hatred in the city—himself received death threats directed against him and his family in the days following his speech. Within three months, Morgan and his family were forced to flee Birmingham.

- James Bevel, a prominent figure within the Civil Rights Movement and organizer of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, was galvanized to create what became known as the Alabama Project for Voting Rights as a direct result of the 16th Street Baptist Church Bombing. Following the bombing, Bevel and his then-wife, Diane, relocated to Alabama, where they tirelessly worked upon the Alabama Project for Voting Rights, which aimed to extend full voting rights for all eligible citizens of Alabama regardless of race. This initiative subsequently contributed to the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches, which themselves resulted in the Voting Rights Act of 1965, thus prohibiting any form of racial discrimination within the process of voting.

-

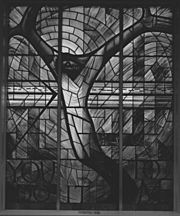

Within the 16th Street Baptist Church, there still stands the Welsh Window. Sculpted by Carmarthenshire-based artist John Petts, who had initiated a campaign in Wales to raise money to fund a replacement stained-glass window which had been destroyed in the bombing. Petts had opted to construct a stained-glass image of a black Christ to replace one of the windows destroyed in the bombing.

The Welsh Window. Designed by artist John Petts, the stained-glass window depicts a black Christ with his arms outstretched; his right arm pushing away hatred and injustice, the left extended in an offering of forgiveness.

The Welsh Window. Designed by artist John Petts, the stained-glass window depicts a black Christ with his arms outstretched; his right arm pushing away hatred and injustice, the left extended in an offering of forgiveness. - Within two days of the church bombing, Petts had contacted then-pastor of the church, the Reverend John Cross, announcing he had launched a fundraising campaign to create this sculpture via an appeal conducted through the Western Mail, requesting funds from the Welsh public to pay for the construction of the structure in Wales, and its delivery and installation at the 16th Street Baptist Church.

- John Petts died in 1991 at the age of 77. In a 1987 interview focusing upon his recollections of the bombing, Petts recollected: "Naturally, as a father, I was horrified by the deaths of those children." Petts then elaborated that the inspiration for the stained-glass image was a verse from the Gospel of Matthew: "Truly, I say to you, as you did it to one of the least of these my brothers, you did it to me." The Welsh Window bears the inscription, "Given by The People of Wales".

- On the 27th anniversary of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, a state historic marker was unveiled at Greenwood Cemetery, the final resting place of three of the four victims of the bombing (Carole Robertson's body had been reburied in Greenwood Cemetery in 1974, following the death of her father). Several dozen people were present at the unveiling, presided over by state Senator Roger Bedford. At the service, the four girls were described as martyrs who "died so freedom could live".

- Herman Frank Cash died of cancer in February 1994. He was never charged with his alleged involvement in the bombing and did maintain his innocence. Although Cash is known to have passed a polygraph test in which he was questioned as to his potential involvement in the bombing, the FBI had concluded in May 1965 that Cash was one of the four conspirators. Cash is interred at Northview Cemetery in Polk County, Georgia.

- The Reverend John Cross, who had been the pastor of the 16th Street Baptist Church at the time of the 1963 bombing, died of natural causes on November 15, 2007. He was 82 years old. The Reverend Cross is interred at Hillandale Memorial Gardens in DeKalb County, Georgia.

- On May 24, 2013, President Barack Obama awarded a posthumous Congressional Gold Medal to the four girls killed in the 1963 Birmingham Church Bombing. This medal was awarded through signing into effect Public Law 113–11; a bill which awarded one Congressional Gold Medal to be created in recognition of the fact the girls' deaths served as a major catalyst for the Civil Rights Movement, and invigorated a momentum ensuring the signing into passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. The gold medal was presented to the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute to display or temporarily loan to other museums.

Media and memorials

Music

- The song "Birmingham Sunday" is directly inspired by the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing. Written in 1964 by Richard Fariña and recorded by Fariña's sister-in-law, Joan Baez, the song was included on Baez's 1964 album Joan Baez/5. The song would also be covered by Rhiannon Giddens, and is included on her 2017 album Freedom Highway.

- Nina Simone's 1964 civil rights anthem "Mississippi Godd**" is partially inspired by the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing. The lyric "Alabama's got me so upset" refers to this incident.

- Jazz musician John Coltrane's 1964 album Live at Birdland includes the track "Alabama", recorded two months after the bombing. This song was written as a direct musical tribute to the victims of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing.

- African-American composer Adolphus Hailstork's 1982 work for wind ensemble titled American Guernica was composed in memory of the victims of the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing.

Film

- A 1997 documentary, 4 Little Girls, exclusively focuses on the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing. Directed by Spike Lee, this documentary includes interviews with family and friends of the victims and received an Academy Award nomination for Best Documentary.

- 2002 docudrama, Sins of the Father, directly focuses on the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing. Directed by Robert Dornhelm, the film casts Richard Jenkins as Bobby Cherry and Bruce McFee as Robert Chambliss.

- The 2014 American historical drama, Selma, which focuses on the 1965 Selma to Montgomery marches, also includes a scene which depicts the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing. This film was directed by Ava DuVernay.

Television

- The 1993 documentary, Angels of Change, focuses on the events leading up to the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing as well as the aftermath of the bombing. This documentary was produced by the Birmingham-based TV station WVTM-TV and subsequently received a Peabody Award.

- The History Channel has broadcast a documentary entitled Remembering the Birmingham Church Bombing. Broadcast to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the bombing, this documentary includes interviews with the head of education at the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute.

Books (fiction)

- Christopher Paul Curtis's 1995 novel The Watsons Go to Birmingham – 1963 conveys the events of the bombing. This fictional account of the bombing was later converted into a movie.

- The 2001 novel Bombingham, written by Anthony Grooms, is set in Birmingham in 1963. This novel portrays a fictional account of the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church and the shootings of Virgil Ware and Johnny Robinson.

- The American Girl book No Ordinary Sound, set in 1963 and featuring the character of Melody Ellison, has the bombing as a major plot point.

In sculpture and symbolism

- Welsh craftsman and artist John Petts was inspired to construct and deliver the iconic stained-glass Welsh Window to the 16th Street Baptist Church in 1965. The Welsh Window is a large stained-glass edifice depicting a black Jesus, with arms outstretched, reminiscent of the Crucifixion of Jesus. Erected at the church in 1965, the Welsh Window stands over the front door of the sanctuary.

- The American sculptor John Henry Waddell has created a memorial symbolizing those killed in the bombing. Entitled That Which Might Have Been: Birmingham 1963, the sculpture—depicting four adult women in differing postures—was created over a period of 15 months. The four women in the sculpture are each depicted in symbolic terms; representing the four victims of the bombing, had they been allowed to mature to womanhood. The sculpture was originally displayed at the First Unitarian Universalist Church in Phoenix in 1969. A second casting of the sculpture was intended for display in Birmingham; this second casting is on display at the George Washington Carver Museum.

- The names of the four girls killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing are engraved upon the Civil Rights Memorial. Erected in Montgomery, Alabama in 1989. The Civil Rights Memorial is an inverted, conical granite fountain and is dedicated to 41 people who died in the struggle for the equal rights and integrated treatment of all people between the years 1954 and 1968. The names of the 41 individuals themselves are chronologically engrained upon the surface of this fountain. Creator Maya Lin has described this sculpture as a "contemplative area; a place to remember the Civil Rights Movement, to honour those killed during the struggle, to appreciate how far the country has come in its quest for equality".

- The Four Spirits sculpture was unveiled at Birmingham's Kelly Ingram Park in September 2013 to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the bombing. Crafted in Berkeley, California by Birmingham-born sculptor Elizabeth MacQueen and designed as a memorial to the four children killed on September 15, 1963, the bronze and steel life-size sculpture depicts the four girls in preparation for the church sermon at the 16th Street Baptist Church in the moments immediately before the explosion. The youngest girl killed in the explosion (Carol Denise McNair) is depicted releasing six doves into the air as she stands tiptoed and barefooted upon a bench as another barefooted girl (Addie Mae Collins) is depicted kneeling upon the bench, affixing a dress sash to McNair; a third girl (Cynthia Wesley) is sat upon the bench alongside McNair and Collins with a Bible in her lap. The fourth girl (Carole Robertson) is depicted standing and smiling as she motions the other three girls to attend their church sermon.

- At the base of the sculpture is an inscription of the title of the sermon the four girls were to attend before the bombing—"A Love That Forgives". More than 1,000 people were present at the unveiling of the memorial, including survivors of the bombing, friends of the victims and the parents of Denise McNair, Johnny Robinson and Virgil Ware.

See also

- African-American history

- African Americans in Alabama

- Racial segregation of churches in the United States

- Timeline of African-American history

- Timeline of the civil rights movement