Alexandru Macedonski facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Alexandru Macedonski

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 14 March 1854 Bucharest, Wallachia |

| Died | 24 November 1920 (aged 66) Bucharest, Kingdom of Romania |

| Pen name | Duna, Luciliu, Sallustiu |

| Occupation | Poet, novelist, short story writer, literary critic, journalist, translator, civil servant |

| Period | 1866–1920 |

| Genre | Lyric poetry, rondel, ballade, ode, sonnet, epigram, epic poetry, pastoral, free verse, prose poetry, fantasy, novella, sketch story, fable, verse drama, tragedy, comedy, tragicomedy, morality play, satire, essay, memoir, biography, travel writing, science fiction |

| Literary movement | Neoromanticism, Parnassianism, Symbolism, Realism, Naturalism, Neoclassicism, Literatorul |

|

|

|

| Signature |  |

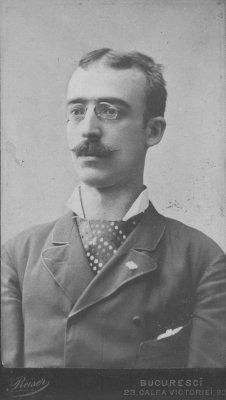

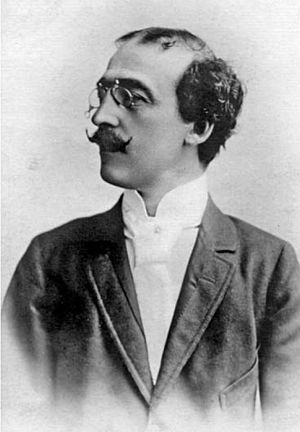

Alexandru Macedonski ( also rendered as Al. A. Macedonski, Macedonschi or Macedonsky; 14 March 1854 – 24 November 1920) was a Romanian poet, novelist, dramatist and literary critic, known especially for having promoted French Symbolism in his native country, and for leading the Romanian Symbolist movement during its early decades. A forerunner of local modernist literature, he is the first local author to have used free verse, and claimed by some to have been the first in modern European literature. Within the framework of Romanian literature, Macedonski is seen by critics as second only to national poet Mihai Eminescu; as leader of a cosmopolitan and aestheticist trend formed around his Literatorul journal, he was diametrically opposed to the inward-looking traditionalism of Eminescu and his school.

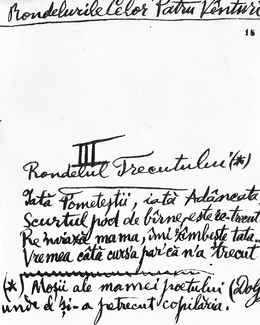

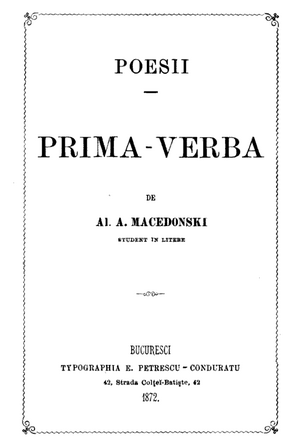

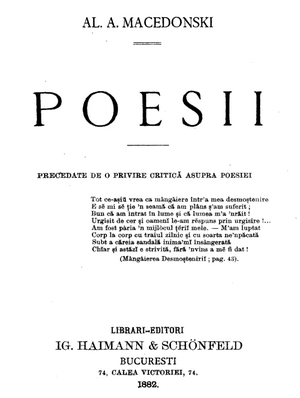

Debuting as a Neoromantic in the Wallachian tradition, Macedonski went through the Realist-Naturalist stage deemed "social poetry", while progressively adapting his style to Symbolism and Parnassianism, and repeatedly but unsuccessfully attempting to impose himself in the Francophone world. Despite having theorized "instrumentalism", which reacted against the traditional guidelines of poetry, he maintained a lifelong connection with Neoclassicism and its ideal of purity. Macedonski's quest for excellence found its foremost expression in his recurring motif of life as a pilgrimage to Mecca, notably used in his critically acclaimed Nights cycle. The stylistic stages of his career are reflected in the collections Prima verba, Poezii, and Excelsior, as well as in the fantasy novel Thalassa, Le Calvaire de feu. In old age, he became the author of rondels, noted for their detached and serene vision of life, in contrast with his earlier combativeness.

In parallel to his literary career, Macedonski was a civil servant, notably serving as prefect in the Budjak and Northern Dobruja during the late 1870s. As journalist and militant, his allegiance fluctuated between the liberal current and conservatism, becoming involved in polemics and controversies of the day. Of the long series of publications he founded, Literatorul was the most influential, notably hosting his early conflicts with the Junimea literary society. These targeted Vasile Alecsandri and especially Eminescu, their context and tone becoming the cause of a major rift between Macedonski and his public. This situation repeated itself in later years, when Macedonski and his Forța Morală magazine began campaigning against the Junimist dramatist Ion Luca Caragiale, whom they falsely accused of plagiarism. During World War I, the poet aggravated his critics by supporting the Central Powers against Romania's alliance with the Entente side. His biography was also marked by an enduring interest in esotericism, numerous attempts to become recognized as an inventor, and an enthusiasm for cycling.

The scion of a political and aristocratic family, the poet was the son of General Alexandru Macedonski, who served as Defense Minister, and the grandson of 1821 rebel Dimitrie Macedonski. Both his son Alexis and grandson Soare were known painters.

Biography

Early life and family

The poet's paternal family had arrived in Wallachia during the early 19th century. Of South Slav (Serb or Bulgarian) or Aromanian origin, they claimed to have descended from Serb insurgents in Ottoman-ruled Macedonia. Alexandru's grandfather Dimitrie and Dimitrie's brother Pavel participated in the 1821 uprising against the Phanariote administration, and in alliance with the Filiki Eteria; Dimitrie made the object of controversy when, during the final stage of the revolt, he sided with the Eteria in its confrontation with Wallachian leader Tudor Vladimirescu. Both Macedonski brothers had careers in the Wallachian military forces, at a time when the country was governed by Imperial Russian envoys, when the Regulamentul Organic regime recognized the family as belonging to Wallachia's nobility. Dimitrie married Zoe, the daughter an ethnic Russian or Polish officer; their son, the Russian-educated Alexandru, climbed in the military and political hierarchy, joining the unified Land Forces after his political ally, Alexander John Cuza, was elected Domnitor and the two Danubian Principalities became united Romania. Both the officer's uncle Pavel and brother Mihail were amateur poets.

Macedonski's mother, Maria Fisența (also Vicenț or Vicența), was from an aristocratic environment, being the scion of Oltenian boyars. Through her father, she may have descended from Russian immigrants who had been absorbed into Oltenia's nobility. Maria had been adopted by the boyar Dumitrache Pârâianu, and the couple had inherited the Adâncata and Pometești estates in Goiești, on the Amaradia Valley.

Both the poet and his father were dissatisfied with accounts of their lineage, contradicting them with an account that researchers have come to consider spurious. Although adherents of the Romanian Orthodox Church, the Macedonskis traced their origin to Rogala-bearing Lithuanian nobility from the defunct Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. While the writer perpetuated his father's claim, it is possible that he also took pride in investigating his Balkan roots: according to literary historian Tudor Vianu, who, as a youth, was a member of his circle, this tendency is attested by two of Macedonski's poems from the 1880s, where the South Slavs appear as icons of freedom. Vianu's contemporary, literary historian George Călinescu, postulated that, although the family had been absorbed into the ethnic and cultural majority, the poet's origin served to enrich local culture by linking it to a "Thracian" tradition and the spirit of "adventurers".

The family moved often, following General Macedonski's postings. Born in Bucharest, Macedonski-son was the third of four siblings, the oldest of whom was a daughter, Caterina. Before the age of six, he was a sickly and nervous child, who is reported to have had regular tantrums. In 1862, his father sent him to school in Oltenia, and he spent most time in the Amaradia region. The nostalgia he felt for the landscape later made him consider writing an Amărăzene ("Amaradians") cycle, of which only one poem was ever completed. He was attending the Carol I High School in Craiova and, according to his official record, graduated in 1867.

Macedonski's father had by then become known as an authoritarian commander, and, during his time in Târgu Ocna, faced a mutiny which only his wife could stop by pleading with the soldiers (an episode which made an impression on the future poet). A stern parent, he took an active part in educating his children. Having briefly served as Defense Minister, the general was mysteriously dismissed by Cuza in 1863, and his pension became the topic of a political scandal. It ended only under the rule of Carol I, Cuza's Hohenzollern successor, when Parliament voted against increasing the sum to the level demanded by its recipient. Having preserved a negative impression of the 1866 plebiscite, during which Cuza's dethronement had been confirmed, Macedonski remained a committed opponent of the new ruler. As a youth and adult, he sought to revive his father's cause, and included allusions to the perceived injustice in at least one poem. After spending the last months of his life protesting against the authorities, Macedonski-father fell ill and died in September 1869, leaving his family to speculate that he had been murdered by political rivals.

Debut years

Macedonski left Romania in 1870, traveling through Austria-Hungary and spending time in Vienna, before visiting Switzerland and possibly other countries; according to one account, it was here that he may have first met (and disliked) his rival poet Mihai Eminescu, at a time a Viennese student. Macedonski's visit was meant to be preparation for entering the University of Bucharest, but he spent much of his time in the bohemian environment, seeking entertainment and engaging in romantic escapades. He was however opposed to the lifestyle choices of people his age. At around that date, the young author had begun to perfect a style heavily influenced by Romanticism, and in particular by his Wallachian predecessors Dimitrie Bolintineanu and Ion Heliade Rădulescu. He was for a while in Styria, at Bad Gleichenberg, a stay which, George Călinescu believes, may have been the result of a medical recommendation to help him counter excessive nervousness. The landscape there inspired him to write an ode. Also in 1870, he published his first lyrics in George Bariț's Transylvanian-based journal Telegraful Român.

The following year, he left for Italy, where he visited Pisa, Florence, Venice, and possibly other cities. His records of the journey indicate that he was faced with financial difficulties and plagued by disease. Macedonski also claimed to have attended college lectures in these cities, and to have spent significant time studying at Pisa University, but this remains uncertain. He eventually returned to Bucharest, where he entered the Faculty of Letters (which he never attended regularly). According to Călinescu, Macedonski "did not feel the need" to attend classes, because "such a young man will expect society to render upon him its homages." He was again in Italy during spring 1872, soon after publishing his debut volume Prima verba (Latin for "First Word"). Having also written an anti-Carol piece, published in Telegraful Român during 1873, Macedonski reportedly feared political reprisals, and decided to make another visit to Styria and Italy while his case was being assessed. It was in Italy that he met French musicologist Jules Combarieu, with whom he corresponded sporadically over the following decades.

During that period, Macedonski became interested in the political scene and political journalism, first as a sympathizer of the liberal-radical current—which, in 1875, organized itself around the National Liberal Party. In 1874, back in Craiova, Macedonski founded a short-lived literary society known as Junimea, a title which purposefully or unwittingly copied that of the influential conservative association with whom he would later quarrel. It was then that he met journalist and pedagogue Ștefan Velescu, a meeting witnessed by Velescu's pupil, the future liberal journalist Constantin Bacalbașa, who recorded it in his memoirs. Oltul magazine, which he had helped establish and which displayed a liberal agenda, continued to be published until July 1875, and featured Macedonski's translations from Pierre-Jean de Béranger, Hector de Charlieu and Alphonse de Lamartine, as well as his debut in travel writing and short story. At age 22, he worked on his first play, a comedy titled Gemenii ("The Twins"). In 1874 that he came to the attention of young journalist future dramatist Ion Luca Caragiale, who satirized him in articles for the magazine Ghimpele, ridiculing his claim to Lithuanian descent, and eventually turning him into the character Aamsky, whose fictional career ends with his death from exhaustion caused by contributing to "for the country's political development". This was the first episode in a consuming polemic between the two figures. Reflecting back on this period in 1892, Macedonski described Caragiale as a "noisy young man" of "sophistic reasoning", whose target audience was to be found in "beer gardens".

1875 trial and office as prefect

In March 1875, Macedonski was arrested on charges of defamation or sedition. For almost a year before, he and Oltul had taken an active part in the campaign against Conservative Party and its leader, Premier Lascăr Catargiu. In this context, he had demanded that the common man "rise up with weapons in their hands and break both the government agents and the government", following up with similar messages aimed at the Domnitor. He was taken to Bucharest's Văcărești prison and confined there for almost three months. Supported by the liberal press and defended by the most prestigious pro-liberal attorneys (Nicolae Fleva among them), Macedonski faced a jury trial on 7 June, being eventually cleared of the charges. Reportedly, the Bucharest populace organized a spontaneous celebration of the verdict.

In 1875, after the National Liberal Ion Emanuel Florescu was assigned the post of Premier by Carol, Macedonski embarked on an administrative career. The poet was upset by not being included on the National Liberal list for the 1875 suffrage. This disenchantment led him into a brief conflict with the young liberal figure Bonifaciu Florescu, only to join him soon afterward in editing Stindardul journal, alongside Pantazi Ghica and George Fălcoianu. The publication followed the line of Nicolae Moret Blaremberg, made notorious for his radical and republican agenda. Ghica and Macedonski remained close friends until Ghica's 1882 death.

The new cabinet eventually appointed him Prefect of Bolgrad region, in the Budjak (at the time part of Romania). In parallel, he published his first translation, a version of Parisina, an 1816 epic poem by Lord Byron, and completed the original works Ithalo and Calul arabului ("The Arab's Horse"). He also spoke at the Romanian Atheneum, presenting his views on the state of Romanian literature (1878). His time in office ended upon the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish War. At the time, Russian volunteers were amassed on the Budjak border, requesting from the Romanian authorities the right of free passage into the Principality of Serbia. The National Liberal Premier Ion Brătianu, who was negotiating an anti-Ottoman alliance, sent Macedonski signals to let them pass, but the prefect, obeying the official recommendation of Internal Affairs Minister George D. Vernescu, decided against it, and was consequently stripped of his office.

Still determined to pursue a career in the press, Macedonski founded a string of unsuccessful magazines with patriotic content and titles such as Vestea ("The Announcement"), Dunărea ("The Danube"), Fulgerul ("The Lightning") and, after 1880, Tarara (an onomatopoeia equivalent to "Toodoodoo"). Their history is connected with that of the Russo-Turkish War, at the end of which Romanian participation on the Russian side resulted in her independence. Macedonski remained committed to the anti-Ottoman cause, and, some thirty years later, stated: "We want no Turkey in Europe!"

By 1879, the poet, who continued to voice criticism of Carol, had several times switched sides between the National Liberals and the opposition Conservatives. That year, while the Budjak was ceded to Russia and Northern Dobruja was integrated into Romania, the Brătianu cabinet appointed him administrator of the Sulina plasă and the Danube Delta. He had previously refused to be made comptroller in Putna County, believing such an appointment to be beneath his capacity, and had lost a National Liberal appointment in Silistra when Southern Dobruja was granted to the Principality of Bulgaria. During this short interval in office, he traveled to the Snake Island in the Black Sea—his appreciation for the place later motivated him to write the fantasy novel Thalassa, Le Calvaire de feu and the poem Lewki.

Early Literatorul years

With the 1880s came a turning point in Alexandru Macedonski's career. Vianu notes that changes took place in the poet's relationship with his public: "Society recognizes in him the nonconformist. [...] The man becomes singular; people start talking about his oddities." Macedonski's presumed frustration at being perceived in this way, Vianu notes, may have led him closer to the idea of poète maudit, theorized earlier by Paul Verlaine. In this context, he had set his sight on promoting "social poetry", the merger between lyricism and political militantism. Meanwhile, according to Călinescu, his attacks on the liberals and the "daft insults he aimed at [Romania's] throne" had effectively ruined his own chance of political advancement.

In January 1880, he launched his most influential and long-lived publication, Literatorul, which was also the focal point of his eclectic cultural circle, and, in later years, of the local Symbolist school. In its first version, the magazine was co-edited by Macedonski, Bonifaciu Florescu and poet Th. M. Stoenescu. Florescu parted with the group soon after, due to a disagreement with Macedonski, and was later attacked by the latter for allegedly accumulating academic posts. Literatorul aimed to irritate Junimist sensibilities from its first issue, when it stated its dislike for "political prejudice in literature." This was most likely an allusion to the views of Junimist figure Titu Maiorescu, being later accompanied by explicit attacks on him and his followers. An early success for the new journal was the warm reception it received from Vasile Alecsandri, a Romantic poet and occasional Junimist whom Macedonski idolized at the time, and the collaboration of popular memoirist Gheorghe Sion. Another such figure was the intellectual V. A. Urechia, whom Macedonski made president of the Literatorul Society. In 1881, Education Minister Urechia granted Macedonski the Bene-Merenti medal 1st class, although, Călinescu stresses, the poet had only totaled 18 months of public service. At around that time, Macedonski had allegedly begun courting actress Aristizza Romanescu, who rejected his advances, leaving him unenthusiastic about love matters and unwilling to seek female company.

In parallel, Macedonski used the magazine to publicize his disagreement with the main Junimist voice, Convorbiri Literare. Among the group of contributors, several had already been victims of Maiorescu's irony: Sion, Urechia, Pantazi Ghica and Petru Grădișteanu. While welcoming the debut of its contributor, Parnassian-Neoclassicist novelist and poet Duiliu Zamfirescu, Macedonski repeatedly attacked its main exponent, the conservative poet Eminescu, claiming not to understand his poetry. However, Literatorul was also open to contributions from some Convorbiri Literare affiliates (Zamfirescu, Matilda Cugler-Poni and Veronica Micle).

In November 1880, Macedonski's plays Iadeș! ("Wishbone!", a comedy first printed in 1882) and Unchiașul Sărăcie ("Old Man Poverty") premiered at the National Theater Bucharest. A sign of government approval, this was followed by Macedonski's appointment to a minor administrative office, as Historical Monuments Inspector. Nevertheless, both plays failed to impose themselves on public perception, and were withdrawn from the program by 1888. Călinescu asserts that, although Macedonski later claimed to have always been facing poverty, his job in the administration, coupled with other sources of revenue, ensured him a comfortable existence.

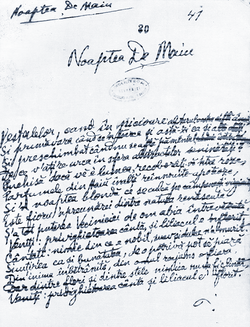

In 1881, Macedonski published a new collection of poetry. Titled Poezii, it carries the year "1882" on its original cover. Again moving away from liberalism, Macedonski sought to make himself accepted by Junimea and Maiorescu. He consequently attended the Junimea sessions, and gave a public reading of Noaptea de noiembrie ("November Night"), the first publicized piece in his lifelong Nights cycle. It reportedly earned him the praise of historian and poet Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu, who, although an anti-Junimist, happened to be in the audience. Despite rumors according to which he had applauded Macedonski, Maiorescu himself was not impressed, and left an unenthusiastic account of the event in his private diary.

First Paris sojourn and Poezia viitorului

Having been stripped of his administrative office by the new Brătianu cabinet, Macedonski faced financial difficulties, and was forced to move into a house on the outskirts of Bucharest, and later moved between houses in northern Bucharest. According to Călinescu, the poet continued to cultivate luxury and passionately invested in the decorative arts, although his source of income, other than the supposed assistance "of [European] ruling houses", remains a mystery. Arguing that Macedonski was "always in need of money" to use on his luxury items, poet Victor Eftimiu claimed: "He did not shy away from sending emphatic notes to the potentates of his day [...], flattering some, threatening others. He would marry off or simply mate some of his disciples with aging and rich women, and then he would squeeze out their assets."

Macedonski eventually left Romania in 1884, visiting Paris. On his way there, he passed through Craiova, where he met aspiring author Traian Demetrescu, whose works he had already hosted in Literatorul and who was to become his friend and protégé. Demetrescu later recalled being gripped by "tremors of emotion" upon first catching sight of Macedonski. In France, Macedonski set up contacts within the French literary environment, and began contributing to French or Francophone literary publications—including the Belgian Symbolist platforms La Wallonie and L'Élan littéraire. His collaboration with La Wallonie alongside Albert Mockel, Tudor Vianu believes, makes Alexandru Macedonski one in the original wave of European Symbolists. This adaptation to Symbolism also drew on his marked Francophilia, which in turn complemented his tendencies toward cosmopolitanism. He became opposed to Carol I, who, in 1881, had been granted the Crown of the Romanian Kingdom. In addition to his admiration for Cuza and the 1848 Wallachian revolutionaries, the poet objected to the King's sympathy for France's main rival, the German Empire. In January 1885, after having returned from the voyage, he announced his retirement from public life, claiming that German influence and its exponents at Junimea had "conquered" Romanian culture, and repeating his claim that Eminescu lacked value.

In the meantime, Literatorul went out of print, although new series were still published at irregular intervals until 1904 (when it ceased being published altogether). The magazine was reportedly hated by the public, causing Macedonski, Stoenescu, Florescu, Urechia and educator Anghel Demetriescu to try to revive it as Revista Literară ("The Literary Review", published for a few months in 1885). The poet attempted to establish other magazines, all of them short-lived, and, in 1887, handed for print his Naturalist novella Dramă banală ("Banal Drama") while completing one of the most revered episodes in the Nights series, Noaptea de mai ("May Night"). Also in 1886, he worked on his other Naturalist novellas: Zi de august ("August Day"), Pe drum de poștă ("On the Stagecoach Trail"), Din carnetul unui dezertor ("From the Notebook of a Deserter"), Între cotețe ("Amidst Hen Houses") and the eponymous Nicu Dereanu.

By 1888, he was again sympathetic toward Blaremberg, whose dissident National Liberal faction had formed an alliance with the Conservatives, editing Stindardul Țărei (later Straja Țărei) as his supporting journal. However, late in the same year, he returned to the liberal mainstream, being assigned a weekly column in Românul newspaper. Two years later, he attempted to relaunch Literatorul under the leadership of liberal figure Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu, but the latter eventually settled for founding his own Revista Nouă. Around 1891, he saluted Junimea's own break with the Conservatives and its entry into politics at the Conservative-Constitutional Party, before offering an enthusiastic welcome to the 1892 Junimist agitation among university students. In 1894, he would speak in front of student crowds gathered at a political rally in University Square, and soon after made himself known for supporting the cause of ethnic Romanians and other underrepresented groups of Austria-Hungary.

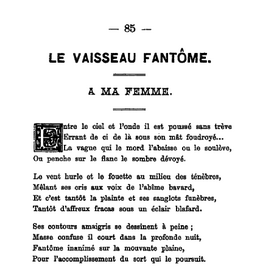

His literary thesis of the time was titled Poezia viitorului ("The Poetry of the Future"). It upheld Symbolist authors as the models to follow, while Macedonski personally began producing what he referred to as "instrumentalist" poems, composed around musical and onomatopoeic elements, and showing a preference for internal rhymes. Such an experimental approach was soon after parodied and ridiculed by Ion Luca Caragiale, who had by then affiliated and parted with Junimea, in his new Moftul Român magazine. The poet sought to reconcile with his rival, publicizing a claim that Caragiale was being unjustly ignored by the cultural establishment, but this attempt failed to mend relations between them, and the conflict escalated further.

While, in 1893, Literatorul hosted fragments of Thalassa in its Romanian-language version, the author also launched a daily, Lumina ("The Light"). It was also at that stage that Alexandru Macedonski associated with Cincinat Pavelescu, the noted epigrammarian, who joined him in editing Literatorul, and with whom he co-authored the 1893 verse tragedy depicting the Biblical hero Saul, and named after him. Although showcased by the National Theater with star actor Constantin Nottara in the title role, it failed to register success with the public. Two years later, the two Literatorul editors made headlines as pioneers of cycling. An enthusiastic promoter of the sport, Macedonski joined fellow poet Constantin Cantilli on a marathon, pedaling from Bucharest across the border into Austria-Hungary, all the way down to Brașov.

Late 1890s

Macedonski also returned with a new volume of poetry, Excelsior (consecutive editions in 1895 and 1896), and founded Liga Ortodoxă ("The Orthodox League"), a magazine noted for hosting the debut of Tudor Arghezi, later one of the most celebrated figures in Romanian literature. Macedonski commended his new protégé for reaching "the summit of poetry and art" at "an age when I was still prattling verses". Liga Ortodoxă also hosted articles against Caragiale, which Macedonski signed with the pseudonym Sallustiu ("Sallustius"). The magazine was additional proof of Macedonski's return to conservatism, and largely dedicated to defending the cause of Romanian Orthodox Metropolitan Ghenadie, deposed by the Romanian Synod following a political scandal. It defended Ghenadie up until he chose to resign, and subsequently went out of print. Macedonski was shocked to note that Ghenadie had given up his own defense.

In 1895, his Casa cu nr. 10 was translated into French by the Journal des Débats, whose editors reportedly found it picturesque. Two years later, Macedonski himself published French-language translations of his earlier poetry under the title Bronzes, a volume prefaced by his disciple, the critic and promoter Alexandru Bogdan-Pitești. Although it was positively reviewed by Mercure de France magazine, Bronzes was largely unnoticed by the French audience.

By 1898, Macedonski was again facing financial difficulties, and his collaborators resorted to organizing a fundraiser in his honor. His rejection of the Orthodox establishment was documented by his political tract, published that year as Falimentul clerului ortodox. Between that time and 1900, he focused on researching esoteric, occult and pseudoscientific subjects. Traian Demetrescu, who recorded his visits with Macedonski, recalled his former mentor being opposed to his positivist take on science, claiming to explain the workings of the Universe in "a different way", through "imagination", but also taking an interest in Camille Flammarion's astronomy studies. Macedonski was determined to interpret death through parapsychological means, and, in 1900, conferenced at the Atheneum on the subject Sufletul și viața viitoare ("The Soul and the Coming Life"). The focal point of his vision was that man could voluntarily stave off death with words and gestures, a concept he elaborated upon in his later articles. In one such piece, Macedonski argued: "man has the power [...] to compact the energy currents known as thoughts to the point where he changes them, according to his own will, into objects or soul-bearing creatures." He also attempted to build a machine for extinguishing chimney fires. Later, Nikita Macedonski registered the invention of nacre-treated paper, which is sometimes attributed to his father.

Return and World War I years=

Macedonski and his protégés had become regular frequenters of Bucharest cafés. Having a table permanently reserved for him at Imperial Hotel's Kübler Coffeehouse, he was later a presence in two other such establishments: High-Life and Terasa Oteteleșanu. He is said to have spent part of his time at Kübler loudly mocking the traditionalist poets who gathered at an opposite table. Meanwhile, the poet's literary club, set up at his house in Dorobanți quarter, had come to resemble a mystical circle, over which he held magisterial command. Vianu, who visited the poet together with Pillat, compares this atmosphere with those created by other "mystics and magi of poetry" (citing as examples Joséphin Péladan, Louis-Nicolas Ménard, Stéphane Mallarmé and Stefan George). The hall where seances were hosted was only lit by candles, and the tables were covered in red fabric. Macedonski himself was seated on a throne designed by Alexis, and adopted a dominant pose. The apparent secrecy and the initiation rites performed on new members were purportedly inspired by Rosicrucianism and the Freemasonry. By then, Macedonski was rewarding his followers' poems with false gemstones.

The poet founded Revista Critică ("The Critical Review"), which again closed after a short while, and issued the poetry volume Flori sacre ("Sacred Flowers"). Grouping his Forța Morală poems and older pieces, it was dedicated to his new generation of followers, whom Macedonski's preface referred to as "the new Romania." He continued to hope that Le Fou? was going to be staged in France, especially after he received some encouragement in the form of articles in Mercure de France and Journal des Débats, but was confronted with the general public's indifference. In 1914, Thalassa was published in a non-definitive version by Constantin Banu's magazine Flacăra, which sought to revive overall interest in his work. At a French Red Cross conference in September, Macedonski paid his final public homage to France, which had just become entangled in World War I. It was also in 1914 that Macedonski commissioned for print his very first rondels and completed work on a tragedy play about Renaissance poet Dante Aligheri—known as La Mort de Dante in its French original, and Moartea lui Dante in the secondary Romanian version (both meaning "Dante's Death"). The aging poet was by then building connections with the local art scene: together with artist Alexandru Severin, he created (and probably presided over) Cenaclul idealist ("The Idealist Club"), which included Symbolist artists and was placed under the honorary patronage of King Carol.

1916 was also the year when Romania abandoned her neutrality and, under a National Liberal government, rallied with the Entente Powers. During the neutrality period, Macedonski had shed his lifelong Francophilia to join the Germanophiles, who wanted to see Romanian participation on the Central Powers' side. In 1915, he issued the journal Cuvântul Meu ("My Word"). Entirely written by him, it published ten consecutive issues before going bankrupt, and notably lashed out against France for being "bourgeois" and "lawyer-filled", demanding from Romania not to get involved in the conflict. Commentators and researchers of his work have declared themselves puzzled by this change in allegiance.

Macedonski further alienated public opinion during the Romanian Campaign, when the Central Powers armies entered southern Romania and occupied Bucharest. Alexis was drafted and became a war artist, but Macedonski Sr, who received formal protection from the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Bucharest, chose to stay behind while the authorities and many ordinary citizens relocated to Iași, where resistance was still being organized. His stance was interpreted as collaborationism by his critics. However, Macedonski reportedly faced extreme poverty throughout the occupation. Having by then begun to attend the circle of Alexandru Bogdan-Pitești, his promoter and fellow Germanophile, he was once rewarded by the latter with a turkey filled with gold coins.

Late polemics, illness and death

Literatorul resumed print in June 1918, once Romania capitulated to the Central Powers under the Treaty of Bucharest.

Alexandru Macedonski faced problems after the Romanian government resumed its control over Bucharest, and during the early years of Greater Romania. What followed the Mackensen article, Vianu claims, was Macedonski's bellum contra omnes ("war against all"). However, the poet made efforts to accommodate himself with the triumphal return of the Iași authorities: in December 1918, Literatorul celebrated the extension of Romanian rule "from the Tisza to the Dniester" as a success of the National Liberals, paying homage to Francophile political leaders Ion I. C. Brătianu and Take Ionescu. Macedonski also envisaged running in the 1918 election for a seat in the new Parliament (which was supposed to vote a document to replace the 1866 Constitution as the organic law), but never registered his candidature. According to Vianu, he had intended to create a joke political party, the "intellectual group", whose other member was an unnamed coffeehouse acquaintance of his. Literatorul was revived for a final time in 1919.

His health deteriorated from heart disease, which is described by Vianu as an effect of constant smoking. By that stage, Vianu recalls, Macedonski also had problems coming to terms with his age. His last anthumous work was the pamphlet Zaherlina (named after the Romanian version of "Zacherlin"; also known as Zacherlina or Zacherlina în continuare, "Zacherlin Contd."), completed in 1919 and published the following year.

Confined to his home by illness and old age, Macedonski was still writing poems, some of which later known as his Ultima verba ("Last Words"). The writer died on 24 November, at three o'clock in the afternoon. He was buried in Bucharest's Bellu.

Work

General characteristics

Although Alexandru Macedonski frequently changed his style and views on literary matters, a number of constants have been traced throughout his work. Thus, a common perception is that his literature had a strongly visual aspect, the notion being condensed in Cincinat Pavelescu's definition of Macedonski: "Poet, therefore painter; painter, therefore poet." Traian Demetrescu too recalled that his mentor had been dreaming of becoming a visual artist, and had eventually settled for turning his son Alexis into one. This pictorial approach to writing created parallels between Macedonski and his traditionalist contemporaries Vasile Alecsandri and Barbu Ștefănescu Delavrancea.

A characteristic of Macedonski's style is his inventive use of Romanian. Initially influenced by Ion Heliade Rădulescu's introduction of Italian-based words to the Romanian lexis, Macedonski himself later infused poetic language with a large array of neologisms from several Romance sources. Likewise, Vianu notes, Macedonski had a tendency for comparing nature with the artificial, the result of this being a "document" of his values. Macedonski's language alternated neologisms with barbarisms, many of which were coined by him personally. They include claviculat ("clavicled", applied to a shoulder), împălăriată ("enhatted", used to define a crowd of hat-wearing tourists), and ureichii (instead of urechii, "to the ear" or "of the ear"). His narratives nevertheless take an interest in recording direct speech, used as a method of characterization. However, Călinescu criticizes Macedonski for using a language which, "although grammatically correct [...], seems to have been learned only recently", as well as for not following other Romanian writers in creating a lasting poetic style.

Critics note that, while Macedonski progressed from one stage to the other, his work fluctuated between artistic accomplishment and mediocrity. At his best, commentators note, he was one of the Romanian literature's classics.

Prima verba and other early works

With Ion Catina, Vasile Păun and Grigore H. Grandea, young Macedonski belonged to late Romanian Romanticism, part of a Neoromantic generation which had for its mentors Heliade Rădulescu and Bolintineanu. Other early influences were Pierre-Jean de Béranger and Gottfried August Bürger, together with Romanian folklore, motifs from them being adapted by Macedonski into pastorals and ballades of ca. 1870–1880. The imprint of Romanticism and such other sources was evident in Prima verba, which groups pieces that Macedonski authored in his early youth, the earliest of them being written when he was just twelve. The poems display his rebellious attitude and strong reliance on autobiographical elements, centering on such episodes as the death of his father.

During his time at Oltul (1873–1875), Macedonski published a series of poems, most of which were not featured in definitive editions of his work. In addition to odes written in the Italian-based version of Romanian, it includes lyrics which satirize Carol I without mentioning his name. Following his arrest, Macedonski also completed Celula mea de la Văcărești ("My Cell in Văcărești"), which shows his attempt to joke about the situation. In contrast to this series, some of the pieces written during Macedonski's time in the Budjak and Northern Dobruja display a detachment from contemporary themes. At that stage, he was especially inspired by Lord Byron, whom Vianu calls "the sovereign poet of [Macedonski's] youth." In Calul arabului, Macedonski explores exotic and Levantine settings, using symbols which announce George Coșbuc's El-Zorab, and the Venetian-themed Ithalo, which centers on episodes of betrayal and murder. Others were epic and patriotic in tone, with subjects such as Romanian victories in the Russo-Turkish War or the Imperial Roman sites along the Danube. One of these pieces, titled Hinov after the village and stone quarry in Rasova, gives Macedonski a claim to being the first modern European poet to have used free verse, ahead of the French Symbolist Gustave Kahn. Macedonski himself later voiced the claim, and referred to such a technique as "symphonic verse", "proteic verse", or, in honor of composer Richard Wagner, "Wagnerian verse".

While editing Oltul, Macedonski also completed his first prose writings. These were the travel account Pompeia și Sorento ("Pompeia and Sorento", 1874) and a prison-themed story described by Vianu as "a tearjerker", titled Câinele din Văcărești ("The Dog in Văcărești", 1875). These were later complemented by other travel works. The short comedy Gemenii was his debut work for the stage. These writings were followed in 1876 by a concise biography of Cârjaliul, an early 19th-century hajduk. In line with his first Levant-themed poems, Macedonski authored the 1877 story Așa se fac banii ("This Is How Money Is Made", later retold in French as Comment on devient riche et puissant, "How to Become Rich and Powerful"), a fable of fatalism and the Muslim world—it dealt with two brothers, one hard-working and one indolent, the latter of whom earns his money through a series of serendipitous events. Likewise, his verse comedy Iadeș! borrowed its theme from the widely circulated collection of Persian literature known as Sindipa. The setting was however modern, and, as noted by French-born critic Frédéric Damé, the plot also borrowed much from Émile Augier's Gabrielle and from other morality plays of the period.

Realism and Naturalism

By the 1880s, Macedonski developed and applied his "social poetry" theory, as branch of Realism. Explained by the writer himself as a reaction against the legacy of Lamartine, it also signified his brief affiliation with the Naturalist current, a radical segment of the Realist movement. Traian Demetrescu thus noted that Macedonski cherished the works of French Naturalists and Realists such as Gustave Flaubert and Émile Zola.

With Unchiașul Sărăcie (also written in verse), Macedonski took Naturalist tenets into the field of drama. Around the time of its completion, Macedonski was also working on a similarly loose adaptation of William Shakespeare's Romeo and Juliet, which notably had the two protagonists die in each other's arms. Another such play is 3 decemvrie ("December 3"), which partly retells Friedrich Ludwig Zacharias Werner's Der 24 Februar using Naturalist devices. By contrast, the homage-play Cuza-Vodă is mainly a Romantic piece, where Alexander John Cuza finds his political mission validated by legendary figures in Romanian history.

By 1880–1884, Macedonski envisaged prioritizing French as his language of expression. Among his pieces of the period is the French-language sonnet Pârle, il me dit alors ("Speak, He Then Said to Me"), where, Vianu notes, "one discovers the state of mind of a poet who decides to expatriate himself."

Adoption of Symbolism

In the early 20th century, fellow poet and critic N. Davidescu described Macedonski, Ion Minulescu and other Symbolists from Wallachia as distinct from their Moldavian counterparts in both style and themes. Endorsing the theory and practice of Symbolism for much of his life, Macedonski retrospectively claimed to have been one of its first exponents.

In his Ospățul lui Pentaur ("The Feast of Pentaur"), the poet reflected on civilization itself. Also during that stage, Macedonski was exploring the numerous links between Symbolism, mysticism and esotericism.

Also at that stage, Macedonski began publishing the "instrumentalist" series of his Symbolist poems. This form of experimental poem was influenced by the theories of René Ghil and verified through his encounter with Remy de Gourmont's views. In parallel, it reaffirmed Macedonski's personal view that music and the spoken word were intimately related (a perspective notably attested by his 1906 interview with Jules Combarieu).

Excelsior

Despite having stated his interest in innovation, Macedonski generally displayed a more conventional style in his Excelsior volume. It included Noaptea de mai, which Vianu sees as "one of the [vernacular's] most beautiful poems" and as evidence of "a clear joy, without any torment whatsoever". A celebration of spring partly evoking folkloric themes, it was made famous by the recurring refrain, Veniți: privighetoarea cântă și liliacul e-nflorit ("Come along: the nightingale is singing and the lilac is in blossom"). Like Noaptea de mai, Lewki (named after and dedicated to the Snake Island), depicts intense joy, completed in this case by what Vianu calls "the restorative touch of nature." The series also returned to Levant settings and Islamic imagery, particularly in Acșam dovalar (named after the Turkish version of Witr). Also noted within the volume is his short "Modern Psalms" series, including the piece Iertare ("Forgiveness").

Late prose works

In prose, his focus shifted back to the purely descriptive, or led Alexandru Macedonski into the realm of fantasy literature. These stories, most of which were eventually collected in Cartea de aur, include memoirs of his childhood in the Amaradia region, nostalgic portrayals of the Oltenian boyar environment, idealized depictions of Cuza's reign, as well as a retrospective view on the end of Rom slavery (found in his piece Verigă țiganul, "Verigă the Gypsy"). The best known among them is Pe drum de poștă, a third-person narrative and thinly disguised memoir, where the characters are an adolescent Alexandru Macedonski and his father, General Macedonski. The idyllic outlook present in such stories is one of the common meeting points between his version of Symbolism and traditionalist authors such as Barbu Ștefănescu Delavrancea.

Particularly during the 1890s, Macedonski was a follower of Edgar Allan Poe and of Gothic fiction in general, producing a Romanian version of Poe's Metzengerstein story, urging his own disciples to translate other such pieces, and adopting "Gothic" themes in his original prose. Indebted to Jules Verne and H. G. Wells, Macedonski also wrote a number of science fiction stories, including the 1913 Oceania-Pacific-Dreadnought, which depicts civilization on the verge of a crisis.

Ultima verba, the very last poems to be written by him, show him coming to terms with himself, and are treasured for their serene or intensely joyous vision of life and human accomplishment.

Legacy

Macedonski's school and its early impact

Alexandru Macedonski repeatedly expressed the thought that, unlike his contemporaries, posterity would judge him a great poet. With the exception of Mihail Dragomirescu, conservative literary critics tended to ignore Macedonski while he was alive.

Many of Macedonski's most devoted disciples, whom he himself had encouraged, have been rated by various critics as secondary or mediocre. This is the case of Theodor Cornel (who made his name as an art critic), Mircea Demetriade, Oreste Georgescu, Alexandru Obedenaru, Stoenescu, Stamatiad, Carol Scrob, Dumitru Karnabatt and Donar Munteanu.

Macedonski's eldest son Alexis continued to pursue a career as a painter. His son Soare followed in his footsteps, receiving acclaim from art critics of the period. Soare's short career ended in 1928, before he turned nineteen, but his works have been featured in several retrospective exhibitions. Another of Alexandru Macedonski's sons, Nikita, was also a poet and painter. For a while in the 1920s, he edited the literary supplement of Universul newspaper. Two years after her father's death, Anna Macedonski married poet Mihail Celarianu.

Macedonski's career was an inspiration for various authors.

Late recognition

Actual recognition of the poet as a classic came only in the interwar period. A final volume of never before published poems, Poema rondelurilor, saw print in 1927.

Macedonski's status as one of Romanian literature's greats was consolidated later in the 20th century. By this time, Noaptea de decemvrie had become one of the most recognizable literary works to be taught in Romanian schools. During the first years of Communist Romania, the Socialist Realist current condemned Symbolism (see Censorship in Communist Romania), but spoke favorably of Macedonski's critique of the bourgeoisie. A while after this episode, Marin Sorescu, one of the best-known modernist poets of his generation, wrote a homage-parody of the Nights cycle. Included in the volume Singur între poeți ("Alone among Poets"), it is seen by critic Mircea Scarlat as Sorescu's most representative such pieces. Also then, Noaptea de decemvrie partly inspired Ștefan Augustin Doinaș' ballad Mistrețul cu colți de argint.

Macedonski's prose influenced younger writers such as Angelo Mitchievici and Anca Maria Mosora. In neighboring Moldova, Macedonski influenced the Neosymbolism of Aureliu Busuioc. In 2006, the Romanian Academy granted posthumous membership to Alexandru Macedonski.

Macedonski's poems had a sizable impact on Romania's popular culture. During communism, Noaptea de mai was the basis for a successful musical adaptation, composed by Marian Nistor and sung by Mirabela Dauer. Tudor Gheorghe, a singer-songwriter inspired by American folk revival, also used some of Macedonski's texts as lyrics to his melodies. In the 2000s, the refrain of Noaptea de mai was mixed into a manea parody by Adrian Copilul Minune.

Works published anthumously

- Prima verba (poetry, 1872)

- Ithalo (poem, 1878)

- Poezii (poetry, 1881/1882)

- Parizina (translation of Parisina, 1882)

- Iadeș! (comedy, 1882)

- Dramă banală (short story, 1887)

- Saul (with Cincinat Pavelescu; tragedy, 1893)

- Excelsior (poetry, 1895)

- Bronzes (poetry, 1897)

- Falimentul clerului ortodox (essay, 1898)

- Cartea de aur (prose, 1902)

- Thalassa, Le Calvaire de feu (novel, 1906; 1914)

- Flori sacre (poetry, 1912)

- Zaherlina (essay, 1920)

See also

In Spanish: Alexandru Macedonski para niños

In Spanish: Alexandru Macedonski para niños