Ariwara no Narihira facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Ariwara no Narihira

|

|

|---|---|

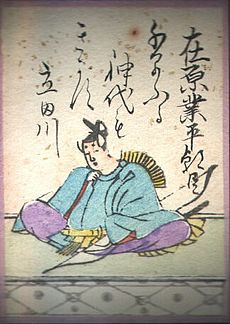

Ariwara no Narihira by Kanō Tan'yū, 1648.

|

|

| Native name |

在原業平

|

| Born | 825 |

| Died | 9 July 880 (aged 54–55) |

| Language | Early Middle Japanese |

| Period | early Heian |

| Genre | waka |

| Subject | nature, romantic love |

| Spouse | unknown |

| Partner | several |

| Children |

|

| Relatives |

|

Ariwara no Narihira (在原 業平, 825 – 9 July 880) was a Japanese courtier and waka poet of the early Heian period. He was named one of both the Six Poetic Geniuses and the Thirty-Six Poetic Geniuses, and one of his poems was included in the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu collection. He is also known as Zai Go-Chūjō, Zai Go, Zai Chūjō or Mukashi-Otoko.

There are 87 poems attributed to Narihira in court anthologies, though some attributions are dubious. Narihira's poems are exceptionally ambiguous; the compilers of the 10th-century Kokin Wakashū thus treated them to relatively long headnotes.

Contents

Biography

Birth and ancestry

Ariwara no Narihira was born in 825. He was a grandson of two emperors: Emperor Heizei through his father, Prince Abo; and Emperor Kanmu through his mother, Princess Ito. He was the fifth child of Prince Abo, but was supposedly the only child of Princess Ito, who lived in the former capital at Nagaoka. Some of Narihira's poems are about his mother.

Abo was banished from the old capital Heijō-kyō (modern Nara) to Tsukushi Province (within modern Fukuoka) in 824 due to his involvement in a failed coup d'état known as the Kusuko Incident. Narihira was born during his father's exile. After Abo's return to Heijō, in 826, Narihira and his brothers Yukihira, Nakahira and Morihira were made commoners and given the surname Ariwara. The scholar Ōe no Otondo was also a brother of Narihira's.

Political career

Although he is remembered mainly for his poetry, Narihira was of high birth and served at court. In 841 he was appointed Lieutenant of the Right Division of Inner Palace Guards, before being promoted to Lieutenant of the Left Division of Inner Palace Guards and then Chamberlain. In 849, he held the Junior Fifth Rank, Lower Grade.

Narihira rose to the positions of Provisional Assistant Master of the Left Military Guard, Assistant Chamberlain, Provisional Minor Captain of the Left Division of Inner Palace Guards, Captain of the Right Division of the Bureau of Horses, Provisional Middle Captain of the Right Division of Inner Palace Guards, Provisional Governor of Sagami, reaching the Junior Fourth Rank, Upper Grade. By the end of his life he had risen to Chamberlain and Provisional Governor of Mino.

Journey to the east

The Kokinshū, Tales of Ise and Tales of Yamato all describe Narihira leaving Kyoto to travel east through the Tōkaidō region and crossing the Sumida River, composing poems at famous places (see utamakura) along the way. The Tales of Ise implies this journey was the result of the scandalous relationship between Narihira and Fujiwara no Takaiko. There are doubts as to whether this journey actually took place, from the point of view both that the number of surviving poems is quite small for having made such a trip and composing poems along the way, and in terms of the historical likelihood that a courtier could have gone wandering to the other end of the country with only one or two friends keeping him company.

Death

According to the Sandai Jitsuroku, Narihira died on 9 July 880 (the 28th day of the fifth month of Tenchō 6 on the Japanese calendar). Poem 861 in the Kokinshū, Narihira's last, expresses his shock and regret that his death should come so soon:

| Japanese text つひにゆく |

Romanized Japanese tsui ni yuku |

English translation Long ago I heard |

Burial site

The location of Narihira's grave is uncertain. In the Middle Ages he was considered a deity (kami) or even an avatar of the Buddha Dainichi, and so it is possible that some what have been called graves of Narihira's are in fact sacred sites consecrated to him rather than places where he was actually believed to have been buried. Kansai University professor and scholar of The Tales of Ise Tokurō Yamamoto (山本登朗, Yamamoto Tokurō) has speculated that the small stone grove on Mount Yoshida in eastern Kyoto known as "Narihira's burial mound" (業平塚, Narihira-zuka) may be such a site. He further speculated that the site became associated with Narihira because it was near the grave-site of Emperor Yōzei, who in the Middle Ages was widely believed to have secretly been fathered by Narihira. Another site traditionally believed to house Narihira's grave is Jūrin-ji (十輪寺) in western Kyoto, which is also known as "Narihira Temple" (なりひら寺, Narihira-dera).

Descendants

Among Narihira's children were the waka poets Muneyana (在原棟梁) and Shigeharu (在原滋春), and at least one daughter. Through Muneyama, he was also the grandfather of the poet Ariwara no Motokata. One of his granddaughters, whose name is not known, was married to Fujiwara no Kunitsune.

Names

Narihira is also known by the nicknames Zai Go-Chūjō (在五中将), Zai Go (在五) and Zai Chūjō (在中将). Zai is the Sino-Japanese reading of the first character of his surname Ariwara, and Go, meaning "five", refers to him and his four brothers Yukihira, Nakahira, Morihira, and Ōe no Otondo. Chūjō ("Middle Captain") is a reference to the post he held near the end of his life, Provisional Middle Captain of the Right Division of Inner Palace Guards. After the recurring use of the phrase in The Tales of Ise, he is also known as Mukashi-Otoko (昔男).

Poetry

Narihira left a private collection, the Narihira-shū (業平集), which was included in the Sanjūrokunin-shū (三十六人集). This was likely compiled by a later editor, after the compilation of the Gosen Wakashū in the mid-10th century.

Thirty poems attributed to Narihira were included in the early 10th-century Kokinshū, and many more in later anthologies, but the attributions are dubious. Ki no Tsurayuki mentioned Narihira in his kana preface to the Kokinshū as one of the Six Poetic Geniuses—important poets of an earlier age. He was also included in Fujiwara no Kintō's later Thirty-Six Poetic Geniuses.

Of the eleven poems the Gosen Wakashū attributed to Narihira, several were really by others—for example, two were actually by Fujiwara no Nakahira and one by Ōshikōchi no Mitsune. The Shin Kokinshū and later court anthologies attribute more poems to Narihira, but many of these were likely misunderstood to have been written by him because of their appearance in The Tales of Ise. Some of these were probably composed after Narihira's death. Combined, poems attributed to Narihira in court anthologies total 87.

The following poem by Narihira was included as No. 17 in Fujiwara no Teika's Ogura Hyakunin Isshu:

| Japanese text ちはやぶる |

Romanized Japanese Chihayaburu |

English translation Even the almighty |

As the karuta "name card" of the main character Chihaya Ayase, the poem appears frequently in the manga and anime Chihayafuru, and its history and meaning are discussed.

Characteristic style

Although at least some of the poems attributed to Narihira in imperial anthologies are dubious, there is a large enough body of his work contained in the relatively reliable Kokinshū for scholars to discuss Narihira's poetic style. Narihira made use of engo (related words) and kakekotoba (pivot words).

The following poem, number 618 in the Kokinshū, is cited by Keene as an example of Narihira's use of engo related to water:

| Japanese text つれづれの |

Romanized Japanese tsurezure no |

English translation Lost in idle brooding. |

The "water" engo are nagame ("brooding", but a pun on naga-ame "long rain"), namidagawa ("a river of tears") and nurete ("is soaked").

Narihira's poems are exceptionally ambiguous by Kokinshū standards, and so were treated by the anthology's compilers to relatively long headnotes. He was the only poet in the collection to receive this treatment. An example of Narihira's characteristic ambiguity that Keene cites is Kokinshū No. 747:

| Japanese text 月やあらぬ |

Romanized Japanese tsuki ya aranu |

English translation Is that not the moon? |

Scholars have subjected this poem, Narihira's most famous, to several conflicting interpretations in recent centuries. The Edo-period kokugaku scholar Motoori Norinaga interpreted the first part of it as a pair of rhetorical questions, marked by the particle ya. He explained away the logical inconsistency with the latter part of the poem that his reading introduced by reading in an "implied" conclusion that though the poet remains the same as before, everything somehow feels different. The late-Edo period waka poet Kagawa Kageki (香川景樹, 1768–1843) took a different view, interpreting the ya as exclamatory: the moon and spring are not those of before, and only the poet himself remains unchanged.

A similar problem of interpretation has also plagued Narihira's last poem (quoted above). The fourth line, kinō kyō to wa, is most normally read as "(I never thought) that it might be yesterday or today", but has been occasionally interpreted by scholars to mean "until yesterday I never thought it might be today"; others take it as simply meaning "right about now". But the emotion behind the poem is nonetheless clear: Narihira, who died in his fifties, always knew he must die someday, but is nonetheless shocked that his time has come so soon.

Connection to The Tales of Ise

The Tales of Ise is a collection of narrative episodes, centred on Narihira, and presenting poems he had composed, along with narratives explaining what had inspired the poems.

Narihira was once widely considered the author of the work, but scholars have come to reject this attribution. Keene speculates that it is at least possible that Narihira originally composed the work from his and others' poems as a kind of inventive autobiography, and some later author came across his manuscript after his death and expanded on it. The protagonist of the work was likely modelled on him. The work itself was likely put together in something resembling its present form by the middle of 10th century, and took several decades starting with Narihira's death.

Three stages have been identified in the composition of the work. The first of these stages would have been based primarily on poems actually composed by Narihira, although the background details provided were not necessarily historical. The second saw poems added to the first layer that were not necessarily by Narihira, and had a higher proportion of fiction to fact. The third and final stage saw some later author adding the use of Narihira's name, and treating him as a legendary figure of the past.

The late 11th-century Tale of Sagoromo refers to Ise by the variant name Zaigo Chūjō no Nikki ("Narihira's diary").

Influence on later Japanese culture

Narihira and his contemporary Ono no Komachi were considered the archetypes of the beautiful man and woman of the Heian court, and appear as such in many later literary works, particularly in Noh theatre.

It is believed Narihira was one of the men who inspired Murasaki Shikibu when she created Hikaru Genji, the protagonist of The Tale of Genji. Genji makes allusion to The Tales of Ise and draws parallels between their respective protagonists. Narihira appears in tales such as 35 and 36 of Book 24 of the late Heian-period Konjaku Monogatarishū.

Along with his contemporary Ono no Komachi and the protagonist of The Tale of Genji, Narihira figured prominently in Edo-period ukiyo-e prints and was alluded to in the ukiyo-zōshi of Ihara Saikaku.

The 16th-century warrior Ōtomo Yoshiaki used Narihira and the courtly world of The Tales of Ise as an ironic reference in a poem he composed about his defeated enemy Tachibana Nagatoshi (立花 長俊), the lord of Tachibana Castle in Chikuzen Province, whom he killed 10 March 1550.

| Japanese text 立花は |

Romanized Japanese Tachibana wa |

English translation Tachibana has |

Gallery

- Ariwara no Narihira image gallery

-

Narihira and Nijō no Tsubone at the Fuji River, woodblock print by Yoshitoshi, 1882

See also

In Spanish: Ariwara no Narihira para niños

In Spanish: Ariwara no Narihira para niños