Rice production in Thailand facts for kids

Rice production in Thailand represents a significant portion of the Thai economy and labor force. In 2017, the value of all Thai rice traded was 174.5 billion baht, about 12.9% of all farm production. Of the 40% of Thais who work in agriculture, 16 million of them are rice farmers by one estimate.

Thailand has a strong tradition of rice production. It has the fifth-largest amount of land under rice cultivation in the world and is the world's second largest exporter of rice. Thailand has plans to further increase the land available for rice production, with a goal of adding 500,000 hectares (1,200,000 acres) to its already 9.2 million hectares (23 million acres) of rice-growing areas. Fully half of Thailand's cultivated land is devoted to rice.

The Thai Ministry of Agriculture projects paddy production for both the main and second crops to hit 27–28 million metric tons (30–31 million short tons) in the 2019–2020 season, dragged down by a drop in second crop production due to floods and drought. Jasmine rice (Thai: ข้าวหอมมะลิ; RTGS: khao hom mali), a higher quality type of rice, is the rice strain most produced in Thailand although in Thailand it is thought that only Surin, Buriram, and Sisaket Provinces can produce high quality hom mali. Jasmine has a significantly lower crop yield than other types of rice, but normally fetches more than double the price of other cultivars on the global market.

Due to ongoing droughts, the USDA has forecast output will drop by more than a fifth to 15.8 million metric tons (17.4 million short tons) in 2016. Thailand can harvest three rice crops a year, but due to water shortages the government is urging a move to less water-dependent crops or forgoing one crop. Rice is water intensive: one calculation says rice requires 1,500 cubic metres (400,000 US gal) of water per cultivated rai.

Contents

History

Until the 1960s, rice planting in Thailand consisted mainly of peasants farming small areas and producing modest amounts of rice. The Chao Phraya River delta was the hub of rice production. Agriculture constituted a large portion of the total production of Thailand and most Thais worked on farms. The extreme focus on agriculture arose for two main reasons: the vast amount of land available for farming and the government's policies of clearing land and protecting peasants' rights. The government helped peasants gain access to land and protected them from aristocratic landlords.

Due to the government's stance, urban merchants were unable to gain much control over the Thai rice industry. The government concerned itself with protecting farmers and not with overall production. As a result, Thailand was relatively self-sufficient, resistant to government intervention, and egalitarian. Most rice farmers owned their own land and exchanged labor between farmers was common. Rice production normally was not much more than the farmers needed to survive on.

As Europe was starting to come together on many issues including agricultural policy (including price supports), Thailand was starting to protect its rice farmers less and work with merchants more. The government started worrying about increasing production and extracting more surplus from the rice industry. Thailand turned to the merchants to put on this pressure and it worked very well.

King Bhumibol played a large part in rice policy during his reign, greatly increasing production. For this he received the first Borlaug Medallion in 2007.

Importance of rice

Rice is central to Thai society. Rice uses over half of the arable land and labor force in Thailand. Of Thailand's eight million farm households in 2020, four million cultivate rice. It is one of the main foods and sources of nutrition for most Thai citizens: yearly per capita consumption in 2013 was 114.57 kg. Rice is also a major Thai export. Despite its importance to the nation, the industry is under threat. According to Dr. Suthad Setboonsarng, the top three threats are, "(i) increase in competition in the international market; (ii) growing competition with other economic activities that increases the cost of production, especially the labour cost; and (iii) degradation of ecological conditions. Rice research has to address these challenges."

Environmental issues

Climate change has and will continue to harm rice yields. A study by Okayama University in Japan found that grain yield declines when the average daily temperature exceeds 29 °C (84 °F), and grain quality continues to decline linearly as temperatures rise.

Another study found that each increasing one degree Celsius change (1.8 degrees Fahrenheit change) in global mean temperature would, on average, reduce yields of rice by 3.2%.

Traditional rice cultivation is the second largest agricultural source of recycled greenhouse gas (GHG) after livestock. Traditional rice production globally accounts for about 4.5% of recycled greenhouse gas emissions. The source of this agricultural methane is organic matter decomposing underwater in flooded paddies. Efforts to decrease agricultural methane (a practice which will help offset single use carbon from fossil fuel use) are being investigated.

Varieties

Jasmine (Hom mali) originates in the country and remains the most popular aromatic cultivar. The Rice Department released five new varieties to celebrate the Coronation of Vajiralongkorn, ahead of the Royal Plowing Ceremony a few days later. Each is named "...62" after BE2562. This is a continuation of the tradition of his ancestor, Chulalongkorn, who founded the royal rice varieties competition. This was first held in 1807 and at first was specifically for the Tung Luang and Rangsit Canal districts. The next year it was held at Wat Suthat, and since then has been held at various locations around the kingdom. Vajiravudh continued the royal encouragement of varietal development, founding the Rangsit Rice Experiment Station in 1816 (now called Pathum Thani Rice Research Center and run by the Ministry). Thailand maintains a rice germplasm collection with 24,000 accessions, of which 20,000 are native Thai types (as of 2009[update]).

Pests

Nilaparvata lugens and Sogatella furcifera are two of the most common. They are commonly controlled with insecticides but can be more cost-effectively controlled by a combination of insecticides and attractive nectar sources to recruit parasitoids (see §Parasitoids below).

Tungro is a constant problem. Oryza officinalis in Sukhothai Province was reported in 1990 to be highly resistant to tungro and several other pests, and already in use in several cultivars for that purpose.

Parasitoids

Anagrus nilaparvatae and A. optibalis are common parasitoids of the above N. lugens and S. furcifera. They are attracted to nectar-producing plants intercropped with rice. Intercropping in this manner is a cost-effective method to increase yields and lower insecticide requirements.

Governmental policy

The government sought to promote urban growth. One of the ways it accomplished this was by taxing the rice industry and using the money in big cities. In 1953, tax on rice accounted for 32% of governmental revenue. The government set a monopoly price on exports, which increased tax revenues and kept domestic prices low in Thailand. The overall effect was income transfer from farmers to the government and to urban consumers (who purchased rice). These policies on rice were called the "rice premium", which was used until 1985 when the government finally gave into political pressure. The shift away from protecting the peasant rice farmers by the government moved the rice industry away from the egalitarian values that were enjoyed by farmers to more of a modern-day, commercial, profit-maximizing industry.

The Thai government had strong incentives to increase rice production and they were successful in most of their plans. The government invested in irrigation, infrastructure, and other pro-rice projects. The World Bank also provided financing for dams, canals, locks, ditches, and other infrastructure in the Greater Chao Phraya Project. Pro-small farm mechanization policies protected agro-machinery manufacturers from outside competition. They also stimulated small machinery research and development that resulted by the late-1990s in nearly two million locally produced two-wheel tractors, as well as one million axial flow pumps for irrigation, hundreds of thousands of small horsepower rice threshers, and 10,000 small horsepower caterpillar track-propelled combines that are able to harvest in small, fragmented, and still wet fields.

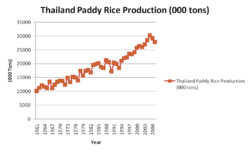

With the combination of improved access to water and machinery, these policies prompted rice farms to increase from 35 million to 59 million rai from the 1950s to the 1980s. Rice production has about tripled in terms of total paddy rice produced. While Thailand's rice production has not increased every year, the trend line shows significant increases since the 1960s.

Starting in 2010 the government went from encouraging rice production to discouraging it. It initiated a program to encourage rice farmers to switch to other crops. The government's policy offered a 2,000 baht per rai subsidy for paddy fields converted to other crops. At the time, Thailand's 54 sugarcane processing plants were short 100 million metric tons (110 million short tons) of raw cane to meet demand. A ready market for sugarcane and the falling price of rice made switching to sugarcane compelling and many farmers made the switch. The transition has not been without controversy: first, because rice is a food staple whereas sugar is not, and secondly, due to undesirable environmental impacts linked to sugarcane farmers' use of between 1.5–2 litres (51–68 US fl oz) of paraquat per rai of sugarcane.

Impact on farmers

While all of these advances helped improve overall production of rice in Thailand, many low-income farmers in Thailand were left worse off. Many peasants were unable to hold on to their land and became tenants. The UN estimates that Thai farmers who owned their own land declined from 44% in 2004 to just 15% in 2011. The government demanded tax revenues, even during bad years, and this pushed many low-income farmers even closer to the margin. Farmers have accumulated 338 billion baht in debt. In 2013, the average household debt in Thailand's northeast was 78,648 baht, slightly lower than the national average of 82,572 baht, according to Thailand's Office of Agricultural Economics (OAE). But the region's average monthly household income, at 19,181 baht, was also lower than the national average, 25,194 baht, according to the National Statistics Office. New technologies have also pushed up the entry cost of rice farming and made it harder for farmers to own their land and produce rice. Many farmers have turned to loan sharks to sustain their operations. In 2015, nearly 150,000 farmers borrowed 21.59 billion baht from these lenders, according to the Provincial Administration Department. Farm debt, mostly incurred by rice farmers, added up to 2.8 trillion baht in 2017. Of Thailand's 21.3 million households, 7.1 million households are farmers. Almost four million Thai households are in debt; 1.1 million of those debtors are farm households.

Farmers who already had large scale operations or could afford all the new chemicals, rice strains, and tractors benefited greatly while the average peasant was turned from a land-owning rice producer to a manual laborer on the farms of others.

Production and exports

Thailand's rise to prominence as a rice producing nation was due to increased production of rice in northeast Thailand. While in the past, central Thailand was the main producer of rice, northeast Thailand quickly caught up. This was in part due to new road systems connecting northeast Thailand to ports on the coastline. Villages that produced significant rice crops were also changing as farmers evolved from more subsistence practices to mostly wage labor. Exchange labor also virtually disappeared.

Working animals were replaced by farm tractors and irrigation technology was updated in most villages. The green revolution was just starting to bloom in the world's farm fields. Rice farmers and merchants took advantage of new rice varieties, strains, fertilizers, and other advances. The International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) disseminated knowledge, technology, new rice strains, and other information to rice producers in Thailand. From the 1950s to 1970s, rice production per unit of land increased by almost 50%.

Thailand exported 10.8 million metric tons (11.9 million short tons) of milled rice valued at US$5.37 billion in 2014, then the highest figure in its history. Rice exports in 2014 represented an increase of 64% in volume and 22% in value compared to 6.6 million metric tons (7.3 million short tons) worth US$4.42 billion exported in 2013. Exports declined in 2015, to 9.8 million metric tons (10.8 million short tons), worth US$4.61 billion, making it the world's second leading exporter of rice behind India, at 10.2 million metric tons (11.2 million short tons). Vietnam was third, exporting 6.61 million metric tons (7.29 million short tons). Exports in 2016 amounted to 9.9 million metric tons (10.9 million short tons). In 2017, Thailand exported 11.63 million metric tons (12.82 million short tons) of rice, an all-time record, up 14.8% year-on-year. Sales revenue rose 15% to 168 billion baht. Of its total annual exports, 70% is commodity-grade white rice and the remainder is hom mali. Some special grades such as riceberry contribute a small quantity. The country exported 11.2 million metric tons (12.3 million short tons) in 2018, but the number plunged to less than 8 million metric tons (8.8 million short tons) in 2019. The decrease is attributed to the strong baht, floods and drought, and increased competition, according to the Thai Rice Exporters Association. Thailand's rice export forecast for 2020 is 7.5 million metric tons (8.3 million short tons).

Ubon Ratchathani Province is the nation's leading rice-producer. It earns more than 10 billion baht a year from rice sales.

Thailand's Future Forward Party has pointed out that, rather than exporting rice solely as a commodity product, it makes more sense to add value to the rice at home and export the resulting product. They point to indicia rice. Thailand has exported since 1980, about 200,000 metric tons (220,000 short tons) of indica rice, sold at 10–20 baht per kilogram, to Japan where Awamori, an alcoholic beverage, is produced in Okinawa. The Japanese-made beverage is exported back to Thailand at 2,500 baht per litre, 170 times the price of the raw material. In Thailand, small producers of liquor are barred from entering the business by the 2017 Excise Tax Act, which mandates a minimum production volume of 30,000 litres per day, effectively closing off opportunities for local craft distilleries.

Competition abroad

India in 2020 was the world's leading rice exporter. Its exported 9.8 million metric tons (10.8 million short tons). Vietnam is fast catching up: it exported 6.4 million metric tons (7.1 million short tons) in 2019. Thai farmers are losing the productivity battle to other nations; in Vietnam, yields range from 800 to 1,000 kilograms (1,764 to 2,205 lb) per rai, while in Thailand yields average 450 kilograms (992 lb) per rai. Vietnam's production costs are estimated to be 50% lower than those in Thailand.

Drought impact

In 2008, drought in Southeast Asia attributed to El Niño drove benchmark Thai rice prices to US$1,000 per metric tonne. In that year, lower Thai rice output, coupled with lower output from India and Vietnam, prompted India to ban exports, sending global prices skyrocketing and causing food riots in Haiti and panic measures by big importers such as the Philippines.

Starting in late-2014, Thailand's rice industry was again hit with a drought that extended to 2016. The drought was accompanied by decreasing worldwide demand for rice. The drought is expected to cost the economy about 84 billion baht (US$2.4 billion) in 2016 and sap demand for durable goods. Farmers are suffering: farm output has declined seven to eight percent in each of the past two years and farmers' debt to agricultural income is around 100%. The military government approved 11.2 billion baht of measures in 2015 to help farmers, including encouraging them to plant crops that need less water. Rice is the primary target of the water use reduction campaign because it requires up to two and a half times more water than wheat or maize. The major dams in the central region, the Bhumibol and Sirikit Dams, the main water sources for the country's central plain, are at their lowest levels since 1994. The government wants to cut rice production to 27 million metric tons (30 million short tons) in the planting season starting May 2016, 25% less than the five-year average.

Land ownership issues

Many farmers are in debt to local businessmen for their mortgages. The percentage of farmers owning land in Thailand has dropped from 44% in 2004 to 15% in 2011. Land rights issues have been exacerbated by political turmoil over the past 15 years. Often new governments fail to honour the land rights commitments made to farmers by past regimes.

Commodity pricing

In 2011, farmers in Thailand could sell a kilogram of rice for 16 baht (US$0.50). In 2016, to make 16 baht, a farmer had to sell three kilograms as the worldwide price of rice declined. The fall in price prompted the military government to introduce rice farmer subsidies of 38 billion baht (US$1.1 billion; £860 million).

A bright spot on the price front is organic rice. At a time when rice millers pay farmers only 7,000 baht per tonne for paddy, organic rice producers can command up to 45,000 baht per tonne. According to Greennet, a non-profit, sales of organic rice increased by 28% in 2016.

Organic rice

Due to a program started over forty years ago by a local monk, Surin Province produces about 4,200 metric tons (4,600 short tons) of organic jasmine rice per year. A local cooperative, the Rice Fund Surin Organic Agriculture Cooperative Ltd, exports its rice to France, Hong Kong, Singapore, Switzerland, and the United States. Surin organic rice farmers receive fifteen baht (US$0.43) per kilogram of paddy, compared with the market price of nine baht per kilo for non-organic jasmine. As the organic rice farmers do not pay for chemical inputs, each can earn about 80,000 baht (US$2,285) per crop on an average-sized farm of 15 rai (2.4 hectares (5.9 acres)). The success of the organic rice cooperative has been identified as one factor in the significant reduction in poverty in Surin as compared with its neighboring province, Sisaket, a province with similar demographics and geography.

Science-based initiatives

Some farmers in northern Thailand have reported success with the System of Rice Intensification (SRI) cultivation methodology. GIZ, the German governmental aid agency, sponsors a pilot "sustainable rice platform" in partnership with the Thai government. Its current (2020) program is called "Thai Rice NAMA" (Nationally Appropriate Mitigation Action), targeting a range of sustainability concerns such as the traditional practice of flooding paddies which contributes releases great quantities of methane to the atmosphere.

Traditions

Rain-making ceremonies are common for rice farmers in Thailand. One such ceremony happens in Bangkok and involves the lord of the Royal Plowing Ceremony throwing rice kernels as he walks around the Grand Palace as the crown prince of Thailand watches. Another tradition that is common to central Thailand is a "cat procession". This involves villagers parading a cat around and throwing water at it, in the belief that a "crying" cat brings a fertile rice crop. The Rice Department released five new varieties to celebrate the Coronation in 2019, ahead of the Royal Plowing Ceremony. These are all named "...62" after BE2562. See [[#Varieties|![]() Varieties]] above.

Varieties]] above.

Rice cartel

Thailand has several times proposed the creation of a rice cartel with Vietnam, Burma, Laos, and Cambodia. Similar to the OPEC cartel that controls oil production, its purpose would be to control production and set prices. Thailand submitted a proposal for such an organization to the other countries, but retracted it in 2008. Analysts believe that such an organization would not be effective, due to the lack of cooperation between the countries and their lack of control over farmers' production. Thailand is now investigating a possible, more forum-based, international organization to discuss supplies and yields of rice.

Noppadon Pattama, the foreign minister of Thailand, wanted to call the forum the "Council on Rice Trade Cooperation" and was planning, as of May 2008, to invite China, India, Pakistan, Cambodia, Burma, and Vietnam to join. Pattama also said the new international forum would not replicate any of the work done by the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI), an institute formed in 1960 to "reduce poverty and hunger, improve the health of rice farmers and consumers, and ensure environmental sustainability of rice farming."

Recognition

At the 2017 World Rice Conference held in Macau, Thailand's hom mali 105 (jasmine) rice was declared the world's best rice, beating 21 competitors. Thailand had entered three rice varieties in the competition. Since 2009 Thai jasmine rice has won the award five times. In 2018, Cambodian Malys Angkor jasmine rice was the winner. Vietnam's ST24 rice took top honours in 2019, causing panic among Thai rice producers as ST24 is half the price of Thai hom mali.