Marcelo H. del Pilar facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Marcelo H. del Pilar

|

|

|---|---|

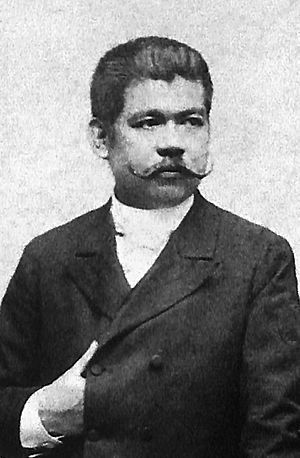

Del Pilar in Madrid, c. 1890

|

|

| Born |

Marcelo Hilario del Pilar y Gatmaitán

August 30, 1850 Bulakan, Bulacan, Captaincy General of the Philippines, Spanish Empire

|

| Died | July 4, 1896 (aged 45) |

| Resting place | Marcelo H. del Pilar Shrine, Bulakan, Bulacan |

| Nationality | Filipino |

| Other names | Pláridel (pen name) |

| Alma mater |

|

| Occupation |

|

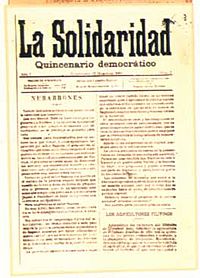

| Organization | La Solidaridad |

| Spouse(s) |

Marciana del Pilar

(m. 1878) |

| Children | 7 |

| Relatives |

|

| Signature | |

Marcelo Hilario del Pilar y Gatmaitán (Spanish: [maɾˈθe.lo iˈla.ɾjo ðel piˈlaɾ]; Tagalog: [maɾˈse.lo ɪˈla.ɾjo del pɪˈlaɾ]; August 30, 1850 – July 4, 1896), commonly known as Marcelo H. del Pilar and also known by his pen name Pláridel, was a Filipino writer, lawyer, journalist, and freemason. Del Pilar, along with José Rizal and Graciano López Jaena, became known as the leaders of the Reform Movement in Spain.

Del Pilar was born and brought up in Bulakan, Bulacan. He was suspended at the Universidad de Santo Tomás and imprisoned in 1869 after he and the parish priest quarreled over exorbitant baptismal fees. In the 1880s, he expanded his anti-friar movement from Malolos to Manila. He went to Spain in 1888 after an order of banishment was issued against him. Twelve months after his arrival in Barcelona, he succeeded López Jaena as editor of the La Solidaridad (Solidarity). Publication of the newspaper stopped in 1895 due to lack of funds. Losing hope in reforms, he grew favorable of a revolution against Spain. He was on his way home in 1896 when he contracted tuberculosis in Barcelona. He later died in a public hospital and was buried in a pauper's grave.

On November 15, 1995, the Technical Committee of the National Heroes Committee, created through Executive Order No. 5 by former President Fidel V. Ramos, recommended del Pilar along with the eight Filipino historical figures to be National Heroes. The recommendations were submitted to Department of Education Secretary Ricardo T. Gloria on November 22, 1995. No action has been taken for these recommended historical figures. In 2009, this issue was revisited in one of the proceedings of the 14th Congress.

Contents

Early life (1850–1880)

Marcelo H. del Pilar was born at his family's ancestral home in sitio Cupang, barrio San Nicolás, Bulacán, Bulacan, on August 30, 1850. He was baptized as "Marcelo Hilario" on September 4, 1850, at the Iglesia Parroquial de Nuestra Señora de la Asuncion in Bulacán. Fr. D. Tomas Yson, a Filipino secular priest, performed the baptism, and Lorenzo Alvir, a distant relative, acted as the godfather. "Hilario" was the original paternal surname of the family. The surname of Marcelo's paternal grandmother, "del Pilar", was added to comply with the naming reforms of Governor-General Narciso Clavería in 1849.

Marcelo's parents belonged to the principalía. Both owned vast tracks of rice and sugarcane farms, fish ponds, and an animal-powered mill. Marcelo's father, Julián Hilario del Pilar (1812-1906), was the son of José Hilario del Pilar and María Roqueza. Don Julián was a famous Tagalog grammarian, writer, and speaker. In the municipality of Bulacán, he served as a "three-time" gobernadorcillo of the town's pueblo (1831, 1854, 1864-1865) and later held the position of oficial de mesa of the alcalde mayor. In the early 1830s, Julián met and married Blasa Gatmaitán (1814-1872?), a descendant of an ancient Tagalog nobility. Known as "Doña Blasica", she was the daughter of Nicolas Gatmaitan and Cerapia De Torres. Don Julián and Doña Blasica had ten children: Toribio (priest, deported to the Mariana Islands in 1872), Fernando (father of Gregorio del Pilar), Andrea, Dorotea, Estanislao, Juan, Hilaria (married to Deodato Arellano), Valentín, Marcelo, and María.

From an early age, del Pilar learned the violin, the piano, and the flute. He also mastered the palasan or rattan cane. In the mid-1850s, del Pilar received early education from his paternal uncle Alejo del Pilar. He pursued his segunda enseñanza at the Colegio de San Juan de Letran under the tutelage of Sr. Mamerto Natividad. The subjects he took there were: Poetry, Doctrina Christiana, Spanish grammar, Latin grammar, Elements of Rhetoric, and Principles of Urbanidad. From July 8, 1865 to January 12, 1866, del Pilar studied under Sr. José Flores in Binondo. Afterward, he enrolled at the Universidad de Santo Tomás to study Philosophy. There, del Pilar earned: (1867-1868) Psychology, Fair; Logic, Fair; Moral Philosophy, Fair; Natural History, Good; Arithmetic, Notablemente; Algebra, Very Good; (1868-1869) Metaphysics 1, Very Good; (1869-1870) Metaphysics 2, Very Good; (1870-1871) Physics, Good.

In 1869, del Pilar acted as a godfather at a baptism in San Miguel, Manila. Surprised by the high rates of baptismal fees in the parish, he argued with the parish priest in the area. The judge, Sr. Félix García Gavieres, favored the parish priest over del Pilar; after the trial, the latter was immediately sent to the Carcel y Presidio Correccional. Del Pilar was pardoned and released from prison thirty days later. Afterward, he resumed his studies at the Universidad de Santo Tomás. He obtained his Bachiller en Filosofía on February 16, 1871. Four and a half months later, on July 2, 1871, del Pilar pursued law.

Out of school, del Pilar worked as oficial de mesa in Pampanga (1874–1875) and Quiapo (1878–1879). In 1876, he resumed his law studies at the Universidad de Santo Tomás. He obtained his licenciado en jurisprudencia, equivalent to a Bachelor of Laws, on March 4, 1881. In law school, del Pilar earned: (1871-1872) Canon Law 1, Fair; Roman Law 1, Very Good; (1873-1874) Canon Law 2, Fair; Roman Law 2, Excellent; (1876-1877) Civil and Mercantile Law, Very Good; (1877-1878) Extension of Civil Law and Spanish Civil Codes, Very Good; Penal Law, Very Good; (1878-1879) Public Law, Fair; Administrative Law, Fair; Colonial Legislation, Fair; Economics, Fair; Political and Statistics, Fair; (1879-1880) Judicial Procedures, Excellent; Practice and Oratory Forensics 1, Excellent; Elements of General Literature and Spanish Literature, Excellent. No grades were recorded for the years 1880-1881 as del Pilar took six months leave.

From 1882 to 1887, del Pilar worked as a defense counselor for the Real Audiencia de Manila. During this time he became active in exposing the existing conditions of the Philippines. Del Pilar attended many events such as funeral wakes, baptismal parties, weddings, town fiestas, and cockfights in the cockpits. Using the Tagalog language, he would talk to different kinds of people like laborers, farmers, fishermen, professionals, and businessmen. In his house in Trozo, Tondo, del Pilar preached nationalistic and patriotic ideas to the young students of Manila. Mariano Ponce, a high school student at the time, was one of his active listeners. Other listeners who would later become his disciples were Briccio Pantas, Numeriano Adriano, and Apolinario Mabini.

Propaganda movement in Spain (1888–1895)

Del Pilar arrived in Barcelona on January 1, 1889. He headed the political section of the Asociación Hispano-Filipina de Madrid (Hispanic Filipino Association of Madrid), an organization of Filipino and Spanish liberals. On February 17, 1889, del Pilar wrote a letter to Rizal, praising the young women of Malolos for their bravery. These twenty-one young women asked the permission of Governor-General Weyler to allow them to open a night school where they could learn to read and write Spanish. With Weyler's approval and over the objections of Fr. Felipe García, the night school opened in 1889. Del Pilar urged Rizal to write a letter in Tagalog to "las muchachas de Malolos," adding that it would be "a help for our champions there and in Manila." In his reply to del Pilar, Rizal shared the handwritten manuscript of the letter he wrote to "las malolesas."

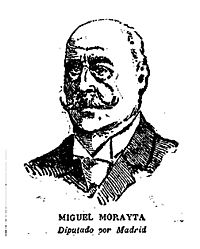

On April 16, 1889, del Pilar met Miguel Morayta y Sagrario in Barcelona. Morayta, an anticlerical and follower of Emilio Castelar, was one of the Spanish liberals who supported the Filipino cause. He was the History Professor of Rizal at the Universidad Central de Madrid and Grand Master of Masons of the Gran Oriente Español. On April 25, 1889, a banquet honoring Morayta was held by del Pilar and other Filipinos in Spain.

In the mid-1889, to further damage the friars' influence and authority in the Philippines, del Pilar and his associates sponsored Fr. Nicolás Manrique Alonso Lallave, an ex-Dominican friar (now a Protestant pastor) assigned in Urdaneta, Pangasinan. Governor-General Rafael Izquierdo deported Lallave to Spain after the latter supported the 1870 decree of Segismundo Moret. In 1872, Lallave wrote an inflammatory pamphlet, entitled Los Frailes en Filipinas (The Friars in the Philippines), wherein he exposed the atrocities of the friars and asked for the termination of the religious orders. He returned to the Philippines in 1889 to establish a Protestant chapel in Manila. Del Pilar wanted to help Lallave through Serrano y Lactao and Sandiko, but before help arrived, the priest died of an illness on June 5, 1889. Some scholars believed that the friars poisoned Lallave.

On December 15, 1889, del Pilar succeeded Graciano López Jaena as editor of the La Solidaridad. Under his editorship, the aims of the newspaper expanded. Using propaganda, it pursued the desires for: assimilation of the Philippines as a province of Spain; removal of the friars and the secularization of the parishes; freedom of assembly and speech; equality before the law; and Philippine representation in the Cortes, the legislature of Spain. A tireless editor, del Pilar wrote under several pseudonyms: Pláridel, Dolores Manapat, Piping Dilat, Siling Labuyo, Cupang, Maytiyaga, Patos, Carmelo, D.A. Murgas, L.O. Crame, Selong, M. Calero, Felipeno, Hilario, Pudpoh, Gregoria de Luna, Dolores Manaksak, M. Dati, and VZKKQJC.

In February 1890, del Pilar met a former Diariong Tagalog colleague, Francisco Calvo y Múñoz. Calvo y Múñoz was one of the Spanish liberals who helped del Pilar in the campaign for the Philippine representation. Calvo y Múñoz's first efforts were on March 3, 1890. At the time he presented to the members of the Cortes an amendment to Article 25 of the Spanish Universal Suffrage Bill. Signed by six deputies, Calvo y Múñoz's amendment called for the restoration of the Philippine parliamentary representation and the election of three deputies from the Philippines. Famous Spanish politicians and liberals were present during Calvo y Múñoz's presentation: Manuel Becerra, the overseas minister under Práxedes Mateo Sagasta; and Antonio Ramos Calderón, a member of Sagasta's Liberal Party. Both spoke after Calvo y Múñoz's presentation. They praised Calvo y Múñoz's intention to restore the Philippine parliamentary representation; however, the two rejected the amendment's early implementation. Despite their statements and judgements, del Pilar, with the help of the Asociación Hispano-Filipina de Madrid, held banquets in honor of Calvo y Múñoz, Becerra, and Ramos Calderón. Del Pilar also featured their speeches in the next issue of La Solidaridad. In a letter dated April 29, 1890, del Pilar said that if Agustín de Burgos y Llamas will succeed Weyler as Governor-General, he may appoint Calvo y Múñoz as the new Director-General of Civil Administration but first the latter should introduce the bill on Philippine representation to the Cortes. Calvo y Múñoz agreed with del Pilar's advice and proposed a more considerate bill the next month. While Calvo y Múñoz was away, del Pilar talked to many deputies to assist in the approval of the bill. Chances for its implementation were halted on July 3, 1890 after the liberal Sagasta was replaced by the conservative Antonio Cánovas del Castillo as Prime Minister of Spain. Del Pilar maintained good relations with the Liberals despite the fell of Sagasta.

In the late 1890, a rivalry developed between del Pilar and Rizal. This was mainly due to the difference between del Pilar's editorial policy and Rizal's political beliefs. On January 1, 1891, about 90 Filipinos gathered in Madrid. They agreed that a Responsable (leader) be elected. Camps were drawn into two, the Pilaristas and the Rizalistas. The first voting for the Responsable started on the first week of February 1891. Rizal won the first two elections but the votes counted for him did not reach the needed two-thirds vote fraction. After Mariano Ponce, instructed by del Pilar, pleaded to the Pilaristas, Rizal was elected Responsable. Rizal, knowing the Pilaristas did not like his political beliefs, respectfully declined the position and transferred it to del Pilar. He then packed up his bags and boarded a train leaving for Biarritz, France. Inactive in the Reform Movement, Rizal ceased his contribution of articles on La Solidaridad.

After the incident, del Pilar wrote a letter of apology to Rizal. Rizal responded and said that he stopped writing for La Solidaridad for reasons: first, he needed time to work on his second novel El filibusterismo (The Reign of Greed); second, he wanted other Filipinos in Spain to work also; and lastly, he could not lead an organization without solidarity in work. Del Pilar and Rizal continued to correspond until the latter's exile to Dapitan in July 1892.

In his later years, del Pilar rejected the assimilationist stand.

On December 11, 1892, Sagasta returned as Prime Minister of Spain with Antonio Maura as the new overseas minister. On December 15, 1892, and January 15, 1893, del Pilar published two articles on La Solidaridad, entitled Ya es tiempo (Is it About Time!) and Insistimos (We Insist), wherein he reminisced the Liberals' pledges and the amendment introduced by Calvo y Múñoz in 1890. Months later, Maura passed two decrees in the Philippines, all put into effect in 1895. The first decree, The Royal Decree of May 19, 1893, was a law that laid the basic foundations for municipal government in the Philippines. It established tribunales, municipales and juntas provinciales. The second decree, The Royal Decree of February 13, 1894, was known as the Maura Act and grew out of a proposal made in the 1820s by Manuel Bernaldez, a long-serving colonial official. Its preamble declared that it would "insure to the natives, in the future, whenever it may be possible, the necessary land for cultivation, in accordance with traditional usages." Despite the passage of these laws, talks regarding the Philippine representation were not entertained. In March 1894, Maura resigned as overseas minister and was replaced by Becerra. Becerra, however, became less sympathetic on the representation of the Philippines and the reforms he proposed. Knowing this, del Pilar approached Emilio Junoy, a friendly deputy and editor-in-chief of La Publicidad. On February 21, 1895, Junoy presented to the Cortes a petition bearing seven thousand signatures. Two weeks later, on March 8, 1895, Junoy delivered a speech to the Spanish Congress wherein he discussed a proposed bill representing the Philippines. Despite del Pilar and Junoy's efforts, the bill did not materialize and on March 23, 1895, Cánovas del Castillo replaced Sagasta again as Prime Minister of Spain.

After years of publication from 1889 to 1895, funding of the La Solidaridad became scarce. Comité de Propaganda's contribution to the newspaper stopped and del Pilar funded the newspaper almost on his own. Advised by Mabini, del Pilar stopped the publication of La Solidaridad on November 15, 1895, with 7 volumes and 160 issues.

Later years, illness, and death (1895–1896)

Del Pilar contracted tuberculosis in November 1895. The following year, he decided to return to the Philippines to lead a revolution. His illness worsened that he had to cancel his journey. On June 20, 1896, he was taken to the Hospital de la Santa Cruz in Barcelona. Del Pilar died at 1:15 a.m. on July 4, 1896, over a month before the Cry of Pugad Lawin. According to Mariano Ponce's account of his death, his last words were: "Please tell my family that I was not able to say goodbye, but that I died with my true friends around me… Pray to God for the good fortune of our country. Continue with your work to attain the happiness and freedom of our beloved country." He was buried the following day in a borrowed grave at the Cementerio del Sub-Oeste (Southwest Cemetery). Before dying, del Pilar retracted from Masonry and received the sacraments of the church.

Reactions after death

- On July 15, 1896, La Politica de España en Filipinas paid tribute to del Pilar by calling him "the greatest journalist ever produced by the purely Filipino race."

- In 1897, former Governor-General Ramón Blanco declared del Pilar as "the most intelligent leader, the real soul of the separatists, very superior to Rizal."

- In La Independencia (1898), Mariano Ponce described del Pilar as "a tireless propagandist" whose powerful intelligence was respected "even by his enemies."

Return of del Pilar's remains and final interment

In 1920, Norberto Romuáldez was commissioned to locate del Pilar's remains. With the help of Joaquín Pellicena y Camacho, the body was exhumed and placed in an urn. Alicante, the ship carrying del Pilar's remains, arrived in Manila on December 3, 1920. From Pier 3 the body was transferred to the Funeraria Nacional. It was taken to Malolos, Bulacan on December 6, 1920. The following day, it was transferred to del Pilar's birthplace in Bulakan, Bulacan. On December 11, 1920, the body lay in state at the Manila Grand Opera House. A necrological service was held at the Salon de Marmol on December 12, 1920. Filipino officials who attended the service were: Manuel C. Briones, representative from Cebu's 1st District; Rafael Palma, senator of the Philippines from the 4th Senatorial District; Teodoro M. Kalaw, secretary of the interior and local government; del Pilar's colleagues in Barcelona and Madrid, Trinidad Pardo de Tavera and Dominador Gómez; Victorino M. Mapa, 2nd Chief Justice of the Philippines; Manuel L. Quezon, senate president of the Philippines; and Sergio Osmeña, 1st Speaker of the Philippine House of Representatives. Del Pilar's wife and two daughters were present during the ceremony. After the service, del Pilar was interred at the Mousoleo de los Veteranos de la Revolución in the Manila North Cemetery.

Del Pilar's remains were transferred to his birthplace on August 30, 1984. His remains were laid to rest under his monument.

Personal life

Marriage, children, and grandchildren

In February 1878, del Pilar married his second cousin Marciana (Chanay) in Tondo. The couple had seven children, five girls and two boys: Sofía, José, María Rosario, María Consolación, María Concepción, José Mariano Leon, and Ana (Anita). Sofía and Anita, the oldest and youngest child, survived to adulthood. On March 12, 1912, Anita married Vicente Marasigan Sr., a businessman from Taal, Batangas. She and her husband had six children: Leticia, Vicente, Benita, Josefina, Antonia, and Marcelo.

Hardships in Spain

Del Pilar's last years in Spain saw his descent into extreme poverty. In a letter to his wife Marciana on August 17, 1892, he wrote: "For my meals, I have to approach friends for loans, day after day. To be able to smoke, I have gone to the extreme of picking up cigarette butts in the streets." In another letter to his wife on August 3, 1893, he told her about his frequent nightmares: "I always dream that I have Anita on my lap and Sofía by her side; that I kiss them by turns and that both tell me: 'Remain with us, papá, and don't return to Madrid'. I awake soaked in tears, and at this very moment that I write this, I cannot contain the tears that drop from my eyes." In June 1893, del Pilar's relatives were able to send money so that he could return to the Philippines. However, his friends (Regidor, Torres, Blumentritt, Morayta, and Quiroga) advised him to stay in Spain. In a letter to his wife on December 21, 1893, he said: "I am afraid of being too hasty, because in view of my present situation, a wrong step on my part will injure many persons, and even if I should pass out of this life, my compatriots would continue to accuse me of imprudence. Note that an error of Rizal's did harm to many (the 1887 Calamba trouble)."

Health

Del Pilar's health was declining before contracting tuberculosis in 1895. He suffered from insomnia, dengue, influenza, rheumatism, and neck tumor.

Connection with the Katipunan

Some historians believe that del Pilar had a direct hand in the Katipunan and its organization because of his role in the Propaganda Movement and his eminent position in Philippine Masonry; most of the Katipunan's founders and members were freemasons. The Katipunan had initiation ceremonies that were copied from masonic rites. It also had a hierarchy of rank that was similar to that of freemasonry.

Bonifacio was also guided by the letters of del Pilar, considering them as "sacred relics" of the revolution.

Alleged testimonies of some Katipuneros

Some Katipuneros have testified that del Pilar instigated the Katipunan. Dr. Jim Richardson, however, questioned the validity of their declarations.

Pío Valenzuela

On September 3, 1896, Pío Valenzuela said that del Pilar had been the President of the Associates of the Katipunan living in Spain.

José Dizon

When the Katipunan was uncovered, José Dizon was among the hundreds who were arrested for rebellion. On September 23, 1896, Dizon was interrogated by Spanish authorities. When asked who carried the instructions for the establishment of the Katipunan, Dizon replied, "Moisés Salvador, he carried with him the instructions of Marcelo H. del Pilar from Madrid... Salvador forwarded the instructions to Deodato Arellano and Andrés Bonifacio".

Águedo del Rosario

On June 28, 1908, Águedo del Rosario said that del Pilar had initiated the formation of the Katipunan. Del Pilar, at the time of the Katipunan's founding, was living in Barcelona.

Historical remembrance

"Father of Philippine Journalism"

For his 150 essays and 66 editorials mostly published in La Solidaridad and various anti-friar pamphlets, del Pilar is widely regarded as the "Father of Philippine Journalism."

Samahang Plaridel, an organization of veteran journalists and communicators, was founded in October 2003 to honor del Pilar's ideals. It also promotes mutual help, cooperation, and understanding among Filipino journalists.

"Father of Philippine Masonry"

Del Pilar was initiated into Freemasonry in 1889. He became an active member of the lodge Revolución in Barcelona. Other members of the lodge were Celso Mir Deas, Ponce, José María Panganiban, López Jaena, Justo Argudin, and Juan José Cañarte. On December 10, 1889, del Pilar joined the revived lodge Solidaridad No. 53 in Madrid. He became its second venerable master, replacing Julio A. Llorente.

Del Pilar worked for the establishment of Filipino Masonic lodges. In 1891, he sent Serrano y Lactao to the Philippines to establish Nilad, the first Filipino Masonic lodge. In 1893, del Pilar also formed the Gran Consejo Regional de Filipinas, the first national organization of Filipino Masons. With these, he earned recognition as the "Father of Philippine Masonry."

The Masonic Grand Lodge of the Philippines, located at 1440 San Marcelino Street in Ermita, Manila, is named Plaridel Masonic Temple.

Historical commemoration

- The Marcelo H. del Pilar Shrine was erected in honor of del Pilar. At the center of the 4,027 square meter site is his 10 feet high monument, made by local sculptor Apolinario Bulaong. At the back of the stadium and the monument stands the mausoleum of the del Pilar family. A two-storey museum library constructed in 1998 can be found at the back of the site. Currently, the shrine is under the management of the National Historical Commission of the Philippines.

- Monuments erected in his honor can be found in Malolos, Paombong, Malate, and Parañaque.

- In 1969, a bronze bust of del Pilar was modelled by classical realist sculptor Anastacio Caedo.

- One of the Plaza Miranda's four corners, "Plaridel Corner", was named after del Pilar. The commemorative plaque, written in Filipino language, bears the following quotation attributed to Voltaire.

(I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.)

- Quingua, a 1st class municipality in the province of Bulacan, was renamed as "Plaridel" in honor of del Pilar.

- A 3rd class municipality in the province of Misamis Occidental was named "Plaridel" in honor of del Pilar.

- A 5th class municipality in the province of Quezon was named "Plaridel" in honor of del Pilar.

- A north–south street connecting Ermita and Malate districts is named Marcelo H. del Pilar Street. It was formerly known as Calle Real (Spanish for "royal street") which served as an arterial road that linked the southern provinces with Manila. In 1921, it was renamed after del Pilar.

- North Luzon Expressway (NLEX), an 84-kilometer (52 mi) limited-access toll expressway that links the provinces of Central Luzon to Metro Manila, was formerly known as the Marcelo H. del Pilar Superhighway.

- One of the streets in Silay City, Negros Occidental is named "Plaridel Street". The Angel Araneta Ledesma Ancestral House is located along the street.

- Marcelo H. del Pilar National High School, a secondary school located in Malolos, is named in honor of del Pilar.

- The building which houses the Graduate School in Polytechnic University of the Philippines was named after del Pilar.

- The building which houses the College of Mass Communication in UP Diliman is named Plaridel Hall in his memory.

- Del Pilar was the inspiration for the U.P. Gawad Plaridel awarded by the College of Mass Communication to outstanding Filipino media practitioners.

- Marcelo H. del Pilar was featured on obverse of the Philippine fifty centavo coin in 1967–72 and again in 1983–94.

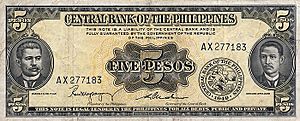

- Del Pilar and Graciano López Jaena appear on the obverse side of a five peso Philippine banknote circulated between 1951 and 1974.

- A 5 centavo postage stamp featuring del Pilar was released on March 3, 1952.

- On April 27, 2022, del Pilar's birth date was declared by President Rodrigo Duterte as National Press Freedom Day.

Notable works

Published during del Pilar's lifetime

- Ang Pagibig sa Tinubúang Lupà (Love for the Native Land, Tagalog translation of Rizal's El Amor Patrio published in the Diariong Tagalog, August 20, 1882)

- La Solídaridad (various articles and essays published under the pen names Pláridel, Carmelo, Patós, D.A. Murgas, and L.O. Crame)

- En Filipinas Quien Manda? (Who is the Master in the Philippines?, published in La Publicidad, December 23, 1887)

- El Monaquismo en Filipinas (Monasticism in the Philippines, published in El Diario under the pen name Piping Dilat, January 12, 1888)

- Viva España! Viva el Rey! Viva el Ejército! Fuera los Frailes! (Long live Spain! Long live the King! Long live the Army! Throw the friars out!, 1888)

- Caiigat Cayó (Be as Slippery as an Eel, published under the pen name Dolores Manapat, August 3, 1888)

- Ang Cadaquilaan nang Dios (The Greatness of God, 1888)

- Noli Me Tángere. Ante el Odio Monacal. (Noli Me Tangere. The Hatred of the Monks., published in La Publicidad under the pen name Pláridel, July 10, 11, 12 and 13, 1888)

- Filipinas Ante la Opinion (The Philippines and Public Opinion, published in El Diluvio, July 27, 1888)

- La Soberanía Monacal en Filipinas (Monastic Supremacy in the Philippines, published under the pen name MH. Pláridel, 1888)

- Dasalan at Tocsohan (Prayers and Mockeries, published under the pen name Dolores Manaksak, 1888)

- Pasióng Dapat Ipag-alab nang Puso nang Tauong Babasa sa Calupitán nang Fraile (The Passion that Should Inflame the Hearts of Those Who Read About the Cruelty of the Friars, 1888)

- Relegacion Gubernativa (Governmental Relegation, published in El Diluvio under the pen name Piping Dilat, January 24, 1889)

- La Asociación Hispano-Filipina (The Asociacion Hispano-Filipina, published in La Publicidad under the pen name Pláridel, January 30, 1889)

- La Frailocracía Filipina (Friarocracy in the Philippines, published under the pen name MH. Pláridel, 1889)

- Sagót nang España sa Hibíc nang Filipinas (Spain's Reply to the Cry of the Philippines, 1889)

- El Triunfo de la Remora en Filipinas (The Triumph of the Enemies of Progress in the Philippines, published in El País under the pen name Pláridel, February 28, 1890)

- Prologo (Prologue of Filipinas en las Cortes, 1890)

- Arancel de los Derechos Parroquiales en las Islas Filipinas publicado con su traduccion tagala (Tagalog translation of Arancel de los Derechos Parroquiales en las Islas Filipinas, 1890)

- Exposicion de la Asociación Hispano-Filipina (Memorial of the Asociacion Hispano-Filipina, February 1, 1892)

- Para Rectificar (A Correction, published in La Justicia, February 11, 1892)

- Otro Peligro Colonial (Another Colonial Danger, published in El Globo, January 19, 1895)

- Canal Bashi (The Bashi Channel, published in El Globo, January 26, 1896)

- Ministerio dela República Filipina (Ministry of the Philippine Republic, 1896)

- La Patria (The Fatherland, 1896)

Published posthumously

- Dupluhan... Dalits... Bugtongs (A Poetical Contest in Narrative Sequence, Psalms, Riddles, 1907)

- Pagina Especial Para la Mujer Filipina (Special Page for the Filipino Woman, published in El Renacimiento, August 28, 1909)

Unpublished works

- Sa Bumabasang Kababayan

- Discurso en El Meeting del Teatro Martin de Madrid (Speech at the Meeting in the Teatro Martin, Madrid)

- Esbozos de Un Codigo Internacional (Spanish translation of David Dudley Field's Outlines of an International Code)

- Proyecto de Estatutos de la Sociedad Financiera de Socorros Mutuos, Titulada la Paz (Proposed by-Laws of the Sociedad Financiera de Socorros Mutuos, Titulada la Paz)

- Reglas de Sintaxis Inglesa (Spanish translation of Rules of English Syntax)

- Progreso del Jefe Gomez: Rapida y Prontamente el Rebelde Principal Trastorna Todas las Combinaciones Españoles (The Progress of Chief Gomez: The Principal Rebel Leader Rapidly and Promptly Upsets All Spanish Combinations)

See also

In Spanish: Marcelo H. del Pilar para niños

In Spanish: Marcelo H. del Pilar para niños